I have been teaching, writing, playing and performing for over thirty-five years, while during these last ten years I have been given the time and space and support (and funds) to create a classroom and pedagogy that through stops and starts...

Literary Analysis Paragraph Rubric

Explicating Themes in Literature

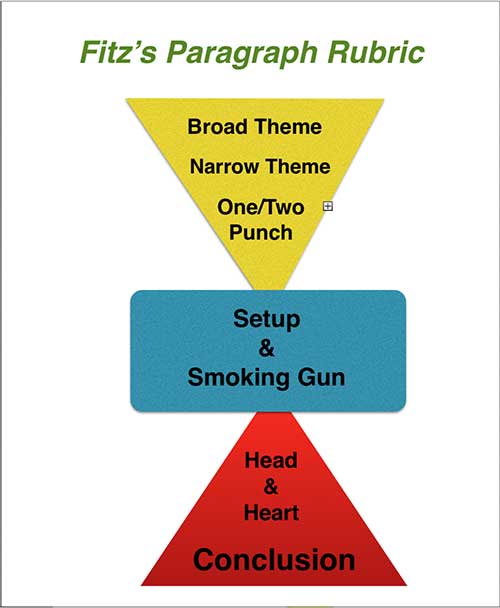

The image above is a visual to help you see what a detailed paragraph includes:

- The first triangle of the paragraph introduces the theme in a broad way, and then narrows it down to a more focused theme that you can effectively write about in a single paragraph.

- The blue rectangle is the central part of your paragraph. It contains the text reference and text support that “proves” your theme is evident in the actual text.

- The bottom triangle contains the head and heart, which, in many ways, should be the most interesting and thoughtful part of your paragraph. It is where you discuss the importance of the theme in the text support and text reference in the smoking gun. See how (as opposed to the upper triangle) it starts narrow and expands to allow you to logically tie back in to your broad theme in your concluding sentence.

Download the Rubric

Feel free (and they are free!) to download and use any Crafted Word Rubrics. When publishing, simply include a link to TheCrafted Word.org and help us spread the news of our site. Thanks

- Literary Paragraph Rubric This is a word doc that you can open in Microsoft Word, Google Docs or in Mac Pages

Common Literary Analysis

Paragraph Mistakes

I am under no illusion that my students are eagerly reading the fine print of my how-to books, but if you are reading this, you are one step closer to being a better writer because knowing what not to do is often as important as knowing what to do!

I have compiled a short list of the most common mistakes writers make when using the literary analysis paragraph rubric. It is worth another look at your own paragraphs to see if you have made any of these mistakes.

FORMATTING MISTAKES

That “first look” at a student’s essay is incredibly important to most teachers. It is our first clue that a student “cares” about the assignment—or doesn’t. It shows us whether or not a student has read and incorporated the details of the assignment into a writing piece.

In the case of the Literary Analysis Paragraph Rubric there are specific directions for where to put the assignment details: name, date, etc; there are guidelines for including a one-word or one phrase theme, and there is a place to put a guiding quote.

Follow any teacher’s guidelines for formatting, and he or she will be on your side after that quick and critical first look !

GUIDING THEME MISTAKES

This comprises the first third of your paragraph and guides the reader in the direction your paragraph. The three parts act together to clearly state the reason your paragraph exists.

- Broad Theme: The most common mistake is to make this a long and complicated sentence. The only purpose of the broad theme is to “engage” the readers interest by introducing an enduring theme and tying it into your narrow theme.

- Narrow Theme: The most common mistake is to omit the one word theme and a specific reference to the literary piece in the sentence. This sentence shows how the broad theme is used in the literary piece.

- One/Two Punch: Don’t go back to your broad theme here; this is the place to narrow down your narrow theme even further to a specific character, event or observation.

TEXT REFERENCE & SUPPORT MISTAKES

This should fill up the center third of your paragraph. It is the physical proof of your theme working within the text of your literary piece.

- Setup: Oftentimes a writer does not provide enough specific detail for the reader to fully understand the context of the coming quote (the smoking gun). Be sure to fully create the “image” a reader needs to “see” by including a meaty and specific who, what, when, where, why leading into the actual text support, AKA: The Smoking Gun.

- Smoking Gun: This can only be the actual text from the literary piece. The most common mistake is to forget to cite the source of the quote, or to forget to italicize the quote–or to forget to block quote the selection if it is longer than two lines on the page.

EXPLICATION & EXPLANATION MISTAKES

Head and Heart: This is the foundation of your paragraph. Without it, your paragraph will be as empty as it is shallow. It shows and tells the reader how your theme is relevant to your text reference. It makes reading your paragraph a worthwhile (edifying) experience.

- Head and Heart: By far the most common mistake here is to write about the theme itself instead of how the theme is specifically used in the piece of literature you are analyzing—and even more specifically how the theme is used in your text reference. Check this section and make sure that “every” sentence refers back to the literary piece (and your narrow theme) in some way shape or form.

TRANSITION OR CONCLUSION

This part of your paragraph should signal your readers that they have either reached their destination or you are talking the next exit off the highway. There is no reason to be wordy here. Too many words is like trying to clear a muddy puddle with your hand. The most common mistake here is referencing your broad theme without referencing the piece of literature you just finished analyzing.

- Get On: The biggest mistake when transitioning to a new paragraph is when there is no logical flow between paragraphs. My rule of thumb is that you “should” be able to put a conjunctive adverb (moreover, finally, however, etc) or a conjunction (so, yet, and,or, nor, for, but) between the last line of one paragraph and the first line of the next. If you can’t do that, there might be something more you need to do….

- Get Out: It is critical to end a final or single paragraph with a sense of finality, so my advice is to finish it clean. The most common mistake here is to introduce a new thought that you haven’t already discussed in your paragraph–or you forget to refer back to your one-word theme AND the literary piece. Never refer back only to the broad theme. This final sentence needs to capture your narrow theme PLUS the added insight of your explanation and explication.

PROOFREADING, EDITING & REVISING

Few things in a student’s life can be as aggravating as receiving a paper back that is full of swirls of red ink and hastily scrolled admonitions to spell correctly, include proper punctuation and grammar, avoid homophones and first person musings. More infuriating might be the fact that your teacher is ignoring your amazing and insightful analysis just because of a few small writing mistakes.

In the end, a mistake is a mistake. All of these “must” be found and corrected by you. Proofread, edit and revise when your mind is fresh and concentration is not a Herculean and Sisyphus-like task. Use a good grammar and spell checker. Let a friend who is particularly good at stuff like this take a look at your work.

Give a damn here and you will be amply rewarded!

The Literary Analysis Paragraph Rubric

“A mighty book requires a mighty theme.”

~Herman Melville

The Literary Analysis Paragraph Rubric

Literary analysis is a type of writing where a writer literally breaks a story down to its most basic elements and then analyzes how and why those elements work in that particular story. These elements include identifying important themes, comparing and contrasting stories and authors, defining writing techniques and devices—and anything else that relates to the way in which a story is structured and told.

Literary analysis deals only in what can be proved objectively via the text, and not because how and why a certain story makes you—as an individual—think and feel subjectively about that story. The Literary Analysis Paragraph #1 is designed to help any writer find and explicate the major themes in a story and to define the importance of these themes in the story. The fact that you, as the analyst, are dealing with objective and provable facts is the main reason why most teachers forbid the use of the “I” voice in this type of writing. It is here where I make the distinction between literary analysis and literary reflection: a literary reflection “reflects” your unique emotional and intellectual response to the story; whereas, a literary analysis “analyzes” the form, devices, style, and content of a story. In an analysis, the “I” is not needed and does not help you prove your point because the point is proved using verifiable facts. Throwing yourself into the mix just muddies the water and burdens your writing with unnecessary words and distractions.

The basic structure of the literary analysis paragraph rubric is, however, essentially the same as the narrative paragraph rubric: you open with a clear and concise guiding theme or topic [broad theme, narrow theme, one/two punch]; you offer supporting facts and proof [smoking gun]; and in your third section of the paragraph, you explain and explicate how your guiding theme relates to the story [head and heart]. Finally, you “get on or get out.” If you are writing a single paragraph, you get out with a sense of finality; if you are writing a multi-paragraph essay, you may need to find a way to transition in a logical and unforced way to the next paragraph in your essay. It is important as a reader, and even more so as a writer, to be able to understand the importance of themes in a piece of literature, for exploring the themes of being human—and being connected (or disconnected) to the rest of humanity is the essential role of any writer!

We don’t read because we care about a writer; and if you are a writer, you need to understand that nobody cares about “you” as a person any more than some guy living three towns over from you; however, we do care about ourselves, and if as a writer you put us in touch with a deeper side of our head and heart; if you pull on the strings of our imagination in such a way that we cry when you want us to cry, laugh when you want us to laugh, and think what you want us to think—then you have succeeded as a writer, and those people who do not care about you as a person will care about what you write, and they will beat a path to your door where they can find the pages that hold your words.

Follow the ten steps…

Literary Analysis Paragraph Rubric

The golden rule of writers is to always know what your readers want and expect—and give it to them in well-crafted writing, which almost always means well-constructed paragraphs! I love using the term “well-crafted” because it implies that writing well requires a deliberate and attentive focus. Good writing is never finished; it is abandoned. Honestly: give yourself ninety minutes to two hours to finish this. A writer’s first words are seldom his or her best words. Over the years I have read and graded thousands of these paragraphs. It is not hard to figure out who gave a damn and who didn’t. It is obvious who reads the details of this rubric before creating his or her own paragraph. So do your best. Give a damn. It works. The image on the sidebar is a visual to help you see what a detailed paragraph includes:

- The first triangle of the paragraph introduces the theme in a broad way, and then narrows it down to a more focused theme that you can effectively write about in a single paragraph.

- The blue rectangle is the central part of your paragraph. It contains the text reference and text support that “proves” your theme is evident in the actual text.

- The bottom triangle contains the head and heart, which, in many ways, should be the most interesting and thoughtful part of your paragraph. It is where you discuss the importance of the theme in the text support and text reference in the smoking gun. See how (as opposed to the upper triangle) it starts narrow and expands to allow you to logically tie back in to your broad theme in your concluding sentence.

Be sure to follow “all” of the details of the rubric explained in the steps below, and try your hand at a creating a well-crafted literary analysis paragraph—one that we call a “whamdammer” in my class! In the rubric that follows, I use an example paragraph written by Ryan Ewing one of my 8th grade students in 2013. The strength of Ryan’s paragraph is not just that it is a good paragraph; it s because he follows the details of the rubric throughout his paragraph. If you wish, replace his text with your own text, then cut and paste your words into a new document and save and submit as required by your teacher. phs. It is not hard to figure out who gave a damn and who didn’t. It is obvious who reads the details of this rubric before creating his or her own paragraph. So do your best. Give a damn. It works. The image on the sidebar is a visual to help you see what a detailed paragraph includes:

- The first triangle of the paragraph introduces the theme in a broad way, and then narrows it down to a more focused theme that you can effectively write about in a single paragraph.

- The blue rectangle is the central part of your paragraph. It contains the text reference and text support that “proves” your theme is evident in the actual text.

- The bottom triangle contains the head and heart, which, in many ways, should be the most interesting and thoughtful part of your paragraph. It is where you discuss the importance of the theme in the text support and text reference in the smoking gun. See how (as opposed to the upper triangle) it starts narrow and expands to allow you to logically tie back in to your broad theme in your concluding sentence.

Be sure to follow “all” of the details of the rubric explained in the steps below, and try your hand at a creating a well-crafted literary analysis paragraph—one that we call a “whamdammer” in my class! In the rubric that follows, I use an example paragraph written by Ryan Ewing one of my 8th grade students in 2013. The strength of Ryan’s paragraph is not just that it is a good paragraph; it s because he follows the details of the rubric throughout his paragraph. If you wish, replace his text with your own text, then cut and paste your words into a new document and save and submit as required by your teacher.

#1: The Assignment Information:

Who are you and what are your writing about?

- As Mae West said, “It is better to look marvellous than to feel marvellous.”

- In that spirit, create assignments that “look” good.

- In the top right corner of your assignment post your name, class, section, assignment name and date.

For Example:

Ryan Ewing

Section One

Fitz English

Huck Finn Paragraph

5/20/20

#2. The Universal Theme

State the unifying theme!

A paragraph needs to have a unifying theme that is developed and explained throughout the paragraph. In this rubric, we are only writing about a single important theme that can be captured n a single word or short phrase.

- Your one word or short phrase theme is the specific aspect of the human condition that is a central theme in the writing piece–but do not mention the writing piece here. It should be centered below your quote and above your opening paragraph in size 18, bold font.

- Your theme should be one word (ideally) or a short phrase—not a full sentence.

For Example:

An Unlikely Friendship

#3. GUIDING QUOTE

Quote from the text that captures your unifying theme.

This quote is by no means “necessary” for a good paragraph, and you would not include it in an essay, but it is a good practice when writing a paragraph, and helps to keep you focused on the theme of your paragraph–and it sets the tone, mood and direction for your reader.

- Choose a quote from the writing piece” that fully captures the theme you wish to explore in your paragraph.

- This quote is the main source for your text reference and text support in your paragraph.

- This can be longer or shorter than you will need or use in your paragraph.

- Center your quote above your paragraph in italics (No quotation marks.) Be sure to cite your source using brackets: For example, [The Odyssey, Book VII, Lines 331-335]

For Example:

Well, I warn’t long making him understand I warn’t dead. I was ever so glad to see Jim. I warn’t lonesome now. I told him I warn’t afraid of HIM telling the people where I was. I talked along, but he only set there and looked at me; never said nothing.

[The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapter VIII]

#4: The Broad Theme

The Universal Theme of the Paragraph!

This is your first sentence of a body paragraph. In a way, it is almost like the “title” of your paragraph. It is meant to indicate the direction of the paragraph in a compelling and interesting way by creating a clear, concise, and memorable statement of a universal theme—a universal reality that relevant, interesting and compelling to your readers.

- Do not mention the writing piece in this sentence because this sentence is supposed to introduce the theme of your paragraph in a general way that is interesting to a potential reader.

- Oftentimes, especially in a longer, multi-paragraph essay, it makes sense to remove this broad theme, but in a one-paragraph response, I’d leave it in there.

For Example:

- Nothing beats spending time with a good friend.

#5. The Narrow Theme

Introduce the Theme in the Literature You Are Analysing

This is essentially the more focused topic sentence of your paragraph—and as such, it is the most important sentence in your paragraph! The Narrow Theme narrows down your theme in a specific way by writing a phrase or sentence that captures how your one-word theme is used in the literature you are analysing. This is your “clear, concise and memorable” topic sentence.

- Be sure to include a specific reference to the writing piece AND a specific reference to your one-word theme in this sentence.

- The narrow theme is the sentence that “steers” your reader in the direction you want him or her to go, and it acts as a reminder to your readers why “exactly” you are writing this paragraph.

For Example:

In the book, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, by Mark Twain, Huck and Jim grow to be two inseparable friends that set out on a great journey together.

#6: The One/Two Punch

Really Narrow Down Your Theme!

- Follow your Narrow Theme with one or two more sentences with what I call the one/two punch that add detail or explanation to your theme and narrows down the topic even further.

- Be sure to mention your theme again in this sentence!

- Think narrow. Beware of creating a series of new topic sentences in your one/two punch.

- At the end of your one/two punch, your readers should have a clear and extremely focused idea of the direction of your paragraph.

For Example:

The two companions go through a lot over their time together, but they never give up on each other. Jim and Huck are as different as people can be, physically; however, it is their similar minds that bring them together as friends.

What about exploring and writing about more than one theme in a single paragraph?

The Literary Analysis Rubric is designed to help writers explicate individual themes in individual paragraphs, but there are occasions where you need or want to explore two or more themes in a single paragraph.

With a bit of tweaking, you can still use the basic rules of this rubric and weave in a discussion and exploration of additional themes within the same paragraph.

My one rule is that there needs to be either a symbiotic relationship between the themes OR an antagonistic relationship that develops in such a way in the story that it is important to discuss the relationship between these themes.

For Example:

Friendship and Hospitality are both major themes in The Odyssey, and it makes a lot of sense to describe the relationship between these two themes.

Likewise, Fate and Free Will are important—although opposite—themes that recur throughout The Odyssey; hence, exploring the roles and relationship of these contradictory themes in the same paragraph makes a lot of sense.

Things to remember…

- Be sure to introduce all of the themes in your broad theme/narrow theme/one-two punch.

- In your setup and smoking gun, do your best to find a single source of text reference and text support that show both or all of your themes in action.

- In your head and heart be sure to show how the themes work together or against each other).

- If any of this is difficult to do, then maybe combining these themes in the same paragraph is not a wise idea!

#7: The Setup

Add Text Reference: Who? What? When? Where? Why?

The setup is the text “reference” that describes in detail (and explicates) the “scene” leading in to your quote (the smoking gun) from the literary piece. The setup and the smoking gun work together to add the “proof” that you have read and studied the piece of literature you are analysing. Without the smoking gun, you are just rambling around and going nowhere—unless your readers are already fully aware of everything that happens in your piece of literature.

- The setup to your smoking gun should include a who, what , when, where, why reference to a scene from the piece of literature you are analysing.

- Use specific images and actions to describe the scene leading into the quote (smoking gun!)

- Notice the colon Ryan uses to “introduce” the quote.

- Notice, too, that he describes this scene in the present tense!

- And he reinforces the theme of friendship again!

For Example:

In the first couple of days after he ran away from his pap’s house, Huck feels very much alone in the vast world that he is hiding in: no friends, no nothing—that is, before he finds Jim. One day, while Huck is out exploring the island, he stumbles upon Jim’s camp; while he is appalled that Jim would run away from Ms. Watson, he is happy that he now has a companion on the island. Even though Jim thinks Huck is a ghost at first, Huck is quick to convince him that he is not:

#8: The Smoking Gun

Adding Quotes The Proof That the Theme Is in the Story!

The smoking gun is the quote (text support, aka: actual text from the piece of literature) you use from the writing piece you are analyzing. A literary analysis without text support is like an egg without a yolk!

- Text reference (setup) and text support (smoking gun) work together to prove you’ve read and analyzed the text and prepares your reader for your head and heart section of the paragraph.

- NOTE: Always include the quote reference after your quote in brackets or parentheses. For example: [The Odyssey, Book One, Lines 234-237]

- It is not always necessary to include the title if it is obvious what literary piece you are writing about.

- “If” your quote is less than two lines as it appears in the final text, put quotation marks at the beginning and end of the quote. Put the quote itself in italics. [This is a personal preference of mine and not a universal “rule” because I feel it helps to identify your text support more clearly and cues the reader more effectively that you are utilizing a quote.]

- If the quote is three lines or more, put the quote in italics without quotation marks; put your quote reference under the quote; create a new paragraph for the quote, and finally, indent (block quote) the whole quote.

- Remember not to indent the first line of the head and heart that comes after the quote because it is still a part of a single paragraph.

For Example:

Well, I warn’t long making him understand I warn’t dead. I was ever so glad to see Jim. I warn’t lonesome now. I told him I warn’t afraid of HIM telling the people where I was. [The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapter VIII]

Using Outside Source Analysis

We only write well about that which we know well, so it is important that a scholar “studies and researches” his or her topic as thoroughly as possible before writing.

It is perfectly acceptable (and I think desirable) to include some references from reputable sources that support your own conclusions and analysis. It not only shows that you are not alone in your thinking, it also shows that you have done more than simply express your own thoughts—it shows you have researched and documented more “proof” that your analysis is valid.

How to cite outside sources…

- It is imperative that you cite any outside source that you use. It is unwise and unethical if you don’t cite in a clear and acceptable way.

- Ask your teacher which format is acceptable. If you are writing on your own, chose the style you wish: MLA, APA, Chicago, etc.

- If you are not sure how to cite a source, look it up online. There are some great resources out there, such as citelighter.com, easybib.com, and a host of others.

Things to remember…

- The best place for outside source material is in the Head & Heart.

- Don’t let outside source material overwhelm your own insights and analysis. It is best to use the source to simply validate your own insights.

- Be sure your outside source is from a reputable scholar—not Sparksnotes, Lit Charts or crowd-sourced sites such as Wikipedia. There is “nothing” wrong with using these sites to help you better understand a writing piece, but it is not considered valid research to cite a semi-anonymous source for a literary analysis.

#9: The Head & Heart

Analyze, Explain & Explicate the Theme in the Passage

This is the “brains & brilliance” part of your paragraph. It shows your reader your how much you know and how insightful you are about your theme and how it used in the literary work you are discussing

- Write at least four sentences that, explicate, illustrate, and elaborate upon your topic sentence and the “Theme” as it used in literary piece, specifically the smoking gun!

- Most teachers do not want you to use the “I” voice, so try to avoid it. You are proving that your theme is in the story, so use the story as proof, not a bunch of “I think…” sentences!

- This is where your passion and knowledge come into play. If you don’t have much head and heart, then I immediately sense a lazy or ill-prepared student—or even worse….

- Notice that Ryan includes several references to friendship (his theme) in his head and heart—which is especially important in the final sentence leading into his conclusion.

- Many writers, in their quest to sound smart and informed, fall into the trap of introducing new and/or irrelevant topics into a paragraph—usually at this point, or they add in more text support. Don’t!!! It distracts and ticks off good readers, and it confuses and frustrates weak readers. Either way, you lose your audience, which is not a good way to earn a living as a writer.

- If you have a new topic that you feel is awesome, then have the decency to give that topic its own paragraph.

For Example:

Huck declares a friend as someone who he can trust; by saying that he was not scared of Jim telling on him, he is showing that he trusts Jim as a good friend. He knows that Jim is the kind of person that would comfort him and give him good company–that is exactly what a good friend does. Huck is white kid who hasn’t quite yet developed feeling for others. Jim, on the other hand, is a slave; however, their similar taste for adventure is what ultimately makes them friends.

Note: It is important to keep hammering home the main theme word or phrase–though you can (and maybe should) use a bit more variation than in here.

- If this paragraph is “transitioning” to a new paragraph, (as is usually the case in an essay) craft your words in a way that sets up the next paragraph. This creates what is called “logical flow.”

- If the paragraph is simply ending, (as in a brief literature response) try and find a way of tying back into your opening theme in a new and refreshing way. This gives your readers a concise and confident visual and mental cue that you have said all you need to say.

- Be sure—one more time—to include a reference to your theme in the conclusion.

For Example: Throughout the rest of the novel, Jim and Huck remain close friends. They come to realize that neither of them could have evaded capture for so long if it weren’t for their friendship. For Huck and Jim, their friendship has allowed them to succeed and thrive together on a difficult journey.

The Rule of Three

The Shop Teachers Rule of Three

- A writing piece is never finished. It is abandoned. Once you are this far, now is the time to go back, edit, revise and to do whatever needs to be done to make this a worthy and enduring piece of literature in its own right.

- Find three areas or sentences that you can make better. If you can’t or won’t do this, then you are light years away from being a writer.

- Often you can find a better broad or narrow theme sentence somewhere else in the paragraph. You can almost always find a more clear and effective way to write a sentence than you wrote on your first try.

- Be sure to read the paragraph aloud, use text to speech to listen, consider making it into a podcast, share it on your blog, and/or post it to your portfolio because you are the writer now. This paragraph is your gift to the world.

- If the rule of three was too easy (meaning you easily found mistakes) do it again…and again if you have to.

I know this is a lot of work for a paragraph (usually at least to hours of good work)–but it is what you need to do if you want to create a clear, concise, compelling, well supported and interesting literary analysis paragraph!

Copy and Paste the Completed Paragraph

Put it all together and edit and revise as needed!

After you have completed all of the steps, put it all together, proofread carefully, edit and revise, and turn in the assignment as required. I have put in bold how often Ryan reinforces the theme of friendship in this paragraph. This emphasis indicate that the paragraph has unity, while the rubric creates logic flow; however, it is the way you craft your words and sentences that gives the paragraph fluency and flow–which is as important as anything!

Ryan Ewing

8th Grade

Fitz English

Section One

Huck Finn Paragraph

5/20/2013

An Unlikely Friendship

Well, I warn’t long making him understand I warn’t dead. I was ever so glad to see Jim. I warn’t lonesome now. I told him I warn’t afraid of HIM telling the people where I was. I talked along, but he only set there and looked at me; never said nothing.

[The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapter VIII]

Nothing beats spending time with a good friend. In the book, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, by Mark Twain, Huck and Jim grow to be two inseparable friends that set out on a great journey together. The two companions go through a lot over their time together, but they never give up on each other. They are as different as people can be, physically; however, it is their similar minds that bring them together as friends. In the first couple of days after he ran away from his pap’s house, Huck feels very much alone in the vast world that he is hiding in; no friends, no nothing—that is, before he finds Jim! One day, while Huck is out exploring the island, he stumbles upon Jim’s camp; while he is appalled that Jim would run away from Ms. Watson, he is happy that he now has a companion on the island. Even though Jim thinks Huck is a ghost at first, Huck is quick to convince him that he is not:

“Well, I warn’t long making him understand I warn’t dead. I was ever so glad to see Jim. I warn’t lonesome now. I told him I warn’t afraid of HIM telling the people where I was.” [The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapter VIII]

Huck declares a friend as someone whom he can trust; by saying that he was not scared of Jim telling on him, he is showing that he trusts Jim as a good friend. He knows that Jim is the kind of person that would comfort him and give him good company—and that is exactly what a good friend does. Huck is white kid who hasn’t quite yet developed feeling for the black slaves that have been so much a part of his life. Jim, on the other hand, is a slave; however, their similar taste for adventure is what ultimately makes them friends. Throughout the rest of the novel, Jim and Huck remain close friends. They come to realize that neither of them could have evaded capture for so long if it weren’t for their friendship. For Huck and Jim, their friendship has allowed them to succeed and thrive together on a difficult journey.

Now that’s a fine looking paragraph!

A+

Explore more of The Crafted Word Rubrics

Recent Comments