TheCraftedWord.org

Tell Your Story

Paragraph & Punctuation

Workshop Two: The Power of Place

Writing Descriptive Paragraphs

The Power of Descriptive Writing

Tell Your Story

Our minds shift gears when filled with imagery: either we slow down and smell the flowers or we shift into a higher gear and our minds become alive with the power and rush that only images and actions can initiate to such great effect—but either way we, as readers, are more alive, ready, and willing to move in a new direction. The writer who does not realize this runs the risk of becoming an erudite prude at best and a self-centered mouthpiece at worst, because his or her words remain untethered to the real world of the reader who instinctively wants and needs to be anchored to a place that gives full breath and breadth to the senses. It is through engaging the senses that a writer engages the reader. To learn the art and craft of descriptive writing is to learn how to tell good story—and in the end, all writing is simply storytelling, good and bad. “This is such bull!” I can almost hear the academic writers crying out in opposition. “We are empowered by ideas and the synthesis and explication of these ‘thought provoking’ nuances of a brilliant mind working towards a solution of a specific and fascinating thesis…” Yeah, they got me there—but only if they got me interested in the first place; only if the tree of my life is already leaning in the direction of that thesis, and only if my mind is ready and willing to plow through the muddy slough that seems to be the field of what is blithely and blindly called “essays.” For me at least to keep plowing through, I need to be reached on not only an intellectual level bit also on the real and palpable visceral levels that completes the fullness of my being being human—the blood, flesh, and bones that keeps the intellect alive. Good, descriptive writing is the vital core that captures not just the mind, but the pumping heart and manifest soul of the reader. Even this—this paltry creation of mine—is being fed not simply by my mind, but by the sublimity of where I am: it is being fed by the first full moon of the summer splaying bits of light through a canopy of woodland forest on a cool New Hampshire night. The dull light of my screen is more than words for me as it attracts more than what is in only in my head; it also attracts a bevy of insects buzzing around or crawling across the hard glass of my page. Yes, I have an audience already! perhaps the only audience this will have, yet it gives every word I eke out a greater meaning and purpose, and without that purpose for me how can there ever be a purpose for you. I learned and accepted long ago that no one intrinsically cares about me and what I write: they care about what my writing gives to them—how it feeds his or her heart, mind, soul, and being. If he or she receives only a glancing blow, I will count this effort a success on the scales of my life as a writer. And if you—the completely unknown you—are still here reading this with some semblance of earnestness that this is time well-spent, then I will reap the unmitigated joy of my words echoing deeper into these dark woods, and I am not alone with this bevy of moths and june-bugs. Good writing separates not only the wheat from the chaff, but also shows the whole process of the winnowing, the drying and grinding of the seeds into the rising flour that becomes the very bread of our lives. My plea is fairly simple: if you are a writer, do not live simply in the guppy thoughts swimming in your head; live in the fullness of your experiences, and cast a net that will strain your gear and haul in a greater catch—a catch that will feed a hungry audience day in and day out. If you are a teacher, let your students write first about what they know best, for if the seed is not in their hands how can it be planted, tended and watered in a garden of joy. Too often our students trudge from the fields of our imposed labors with hands, heads and hearts deadened by defeat—proud warriors once, but no more. Keep the passion alive. Keep the passion alive. Keep the passion alive. Let every essay, every writing prompt, and every scratch upon the page be a story well told. Teach how to tell good stories; teach how to use descriptive writing to perfect and enliven those stories, and share those stories, and curate those stories. But let each writer tell his or her own story. And you tell yours.

Our minds shift gears when filled with imagery: either we slow down and smell the flowers or we shift into a higher gear and our minds become alive with the power and rush that only images and actions can initiate to such great effect—but either way we, as readers, are more alive, ready, and willing to move in a new direction. The writer who does not realize this runs the risk of becoming an erudite prude at best and a self-centered mouthpiece at worst, because his or her words remain untethered to the real world of the reader who instinctively wants and needs to be anchored to a place that gives full breath and breadth to the senses. It is through engaging the senses that a writer engages the reader. To learn the art and craft of descriptive writing is to learn how to tell good story—and in the end, all writing is simply storytelling, good and bad. “This is such bull!” I can almost hear the academic writers crying out in opposition. “We are empowered by ideas and the synthesis and explication of these ‘thought provoking’ nuances of a brilliant mind working towards a solution of a specific and fascinating thesis…” Yeah, they got me there—but only if they got me interested in the first place; only if the tree of my life is already leaning in the direction of that thesis, and only if my mind is ready and willing to plow through the muddy slough that seems to be the field of what is blithely and blindly called “essays.” For me at least to keep plowing through, I need to be reached on not only an intellectual level bit also on the real and palpable visceral levels that completes the fullness of my being being human—the blood, flesh, and bones that keeps the intellect alive. Good, descriptive writing is the vital core that captures not just the mind, but the pumping heart and manifest soul of the reader. Even this—this paltry creation of mine—is being fed not simply by my mind, but by the sublimity of where I am: it is being fed by the first full moon of the summer splaying bits of light through a canopy of woodland forest on a cool New Hampshire night. The dull light of my screen is more than words for me as it attracts more than what is in only in my head; it also attracts a bevy of insects buzzing around or crawling across the hard glass of my page. Yes, I have an audience already! perhaps the only audience this will have, yet it gives every word I eke out a greater meaning and purpose, and without that purpose for me how can there ever be a purpose for you. I learned and accepted long ago that no one intrinsically cares about me and what I write: they care about what my writing gives to them—how it feeds his or her heart, mind, soul, and being. If he or she receives only a glancing blow, I will count this effort a success on the scales of my life as a writer. And if you—the completely unknown you—are still here reading this with some semblance of earnestness that this is time well-spent, then I will reap the unmitigated joy of my words echoing deeper into these dark woods, and I am not alone with this bevy of moths and june-bugs. Good writing separates not only the wheat from the chaff, but also shows the whole process of the winnowing, the drying and grinding of the seeds into the rising flour that becomes the very bread of our lives. My plea is fairly simple: if you are a writer, do not live simply in the guppy thoughts swimming in your head; live in the fullness of your experiences, and cast a net that will strain your gear and haul in a greater catch—a catch that will feed a hungry audience day in and day out. If you are a teacher, let your students write first about what they know best, for if the seed is not in their hands how can it be planted, tended and watered in a garden of joy. Too often our students trudge from the fields of our imposed labors with hands, heads and hearts deadened by defeat—proud warriors once, but no more. Keep the passion alive. Keep the passion alive. Keep the passion alive. Let every essay, every writing prompt, and every scratch upon the page be a story well told. Teach how to tell good stories; teach how to use descriptive writing to perfect and enliven those stories, and share those stories, and curate those stories. But let each writer tell his or her own story. And you tell yours.

Writing Genres

The Top “Eleven” Ways To Create Content for Your Blog

Doing something which is “different” does not come easily to most of us. The wrestling team I coach will look at me sideways if I ask them to practice cartwheels. I’ve even heard that some professional football teams bring in dance instructors to teach their behemoth linemen the art of ballet and the foxtrot. My point is that practicing “any” athletic sport develops your skill in another seemingly unrelated sport. The same is true in writing. Through practicing the skills and techniques used in different genres of writing, we can enhance the overall quality and effectiveness of the writing we love to do (or are required to do because of schoolwork or employment). By practicing different styles and genres of writing, we learn to avoid the rut of developing a formulaic, predictable, and downright dull writing style—plus, you might even discover a renewed love and energy for a “new” kind of writing when you practice writing in an unfamiliar genre.

Doing something which is “different” does not come easily to most of us. The wrestling team I coach will look at me sideways if I ask them to practice cartwheels. I’ve even heard that some professional football teams bring in dance instructors to teach their behemoth linemen the art of ballet and the foxtrot. My point is that practicing “any” athletic sport develops your skill in another seemingly unrelated sport. The same is true in writing. Through practicing the skills and techniques used in different genres of writing, we can enhance the overall quality and effectiveness of the writing we love to do (or are required to do because of schoolwork or employment). By practicing different styles and genres of writing, we learn to avoid the rut of developing a formulaic, predictable, and downright dull writing style—plus, you might even discover a renewed love and energy for a “new” kind of writing when you practice writing in an unfamiliar genre.

Make a commitment to try and write in each of the following genres and styles of writing when posting to your blog or adding content to your digital portfolio. I will post more detailed descriptions and writing prompts that span the many different types of writing, but it is up to you to give them a full-hearted try. Good luck and have fun! 1. Your Daily Journal: Every good writer keeps a journal that remembers the daily events of his or her life, no matter how mundane or common. A daily journal is a recording of your life as live it, and as such, it is a treasure trove of memories that you can draw from later in life—memories and snapshots that you can expand upon in a more formal writing piece any time you wish. 2. The Ramble: The Ramble (often called ‘free-writing’) is closely related to the daily journal, but it is more of a free-flowing series of thoughts, ideas and experiences. It is a journey with your mind and heart and soul down an emotional and intellectual highway. The ramble does not have to have a formal structure, but it does try to find and focus on a specific theme, and it does try and punctuate and paragraph to the best of your ability. By defining a certain post as a ramble, you are freed from all criticism of your writing style and technique because you are simply on an exploration of yourself, and as such, it is hard to go wrong! Rambles are great fun and an invigorating exercise in writing, but it is what it is. The writings of one of Jack Kerouac aside (a writer who wrote entire books as rambles) it is a misnomer to call a ramble anything but a ramble. I have had many chagrined students who tried to pass off their ramble as a thinly disguised essay—but, many a good ramble of mine have been reincarnated as an essay. 3. The Personal Narrative: Personal Narratives are the stories of our lives. By habitually practicing the art of storytelling through personal narratives, we practice the basic craft of the Short Story and the Essay. By telling the stories of our lives, we follow the main rule of all writing: write about what you know! I could write all day about the joy of Bungee jumping, and I still couldn’t convince a toad that I knew what I was talking about. But if I wrote about the day I watched people bungee jumping off a bridge, then I could probably get that toad to publish the story for me. I could be the protagonist, and my best friend forcing me to try could be the antagonist; fear of jumping into the unknown could be the conflict; standing up to my friend could be the climax; falling out of a tree when I was young could be my supporting facts; facing and trying to overcome my fears could become the theme of my essay/story, and when a reader can relate to your theme, they are able to recreate your story in their own imaginations. It might force them to think about their own fears, and in doing so, your story effects a powerful transformations in their lives. Every day and every experience is a possible personal narrative. If that experience means anything to you, it will mean the same thing to someone else because we are all tied together by our “common humanity;” we share the same emotional connections, but how we experience those emotions is infinite and infinitely varied—and that is why our libraries and bookshelves are filled, and that is why we all keep returning to the power and creative magic of literature. Think of everything you write as true literature. 4. Memoirs: The way in which a person or place or thing affects your life is a profound statement of your values and an enduring testament a specific person’s influence on your life. A memoir is a type of personal narrative that paints a vivid portrait of an interesting and worthy character, place or thing. Through images and actions, thoughts, feelings and memories you, as a writer, recreate the power and magic that has left an indelible mark on your life. Every good novelist and short story writer is a master of the memoir because writing memoirs is the key to developing dynamic, real and empathetic characters and compelling stories of places and things, without which a story falls flat on its face! 5. Short Stories: Every writer is essentially a storyteller, but the craft of short story writing requires a discipline and attention to detail that most writers are not willing to undertake. A good short story effectively creates a powerful experience for the reader out of the writer’s imagination and experience. Most beginning short story writers bite off more than they can chew; they attempt to scale a high peak without first learning how to tie their boots. I will write more in a future post, but for now keep it simple: don’t write stories with a bunch of different characters. Two or three characters is all a good short story needs! Make the plot easy to follow, and be sure that there is a clear protagonist and a clear antagonist and a clear conflict. Most importantly, create characters that you can relate to on a personal level. If you are ten years old, make your main character a ten year old, because that is what you know best, and you can recreate experiences for your reader that are compelling and real. And remember that your first draft is never ever your best draft! 6. Poetry: Poetry is the highest art. A great writer is not always a great poet, but a great poet is always a great writer. Poetry is the hardest genre to pin down and say, “This is poetry!” Poetry is the rough gem of life polished to perfection. To write poetry, you need to simply ask yourself: “Why is this a poem?” A poem is more than thoughts expressed in short lines; it is the meticulous crafting, choosing and placing of words, lines, spaces, breaths, and stanzas that defines what you call a poem. This is all up to you as the poet. I can’t tell you what is and what is not a poem, but I can tell you that good poets read the poems of other good poets, and they spend huge amounts of time on their own poetry. With practice comes skill; with skill comes perfection, and poetry will only happen in this order. The first skill of a poet is to ask, “Why am I writing this?” The second skill of a poet is to ask, “Did I tell my reader something, or did I lead them somewhere and show them something?” Don’t give the meaning of a poem away, but do leave clues for the reader to find that meaning. 7. Personal Reflections: I love personal reflections. There are few joys greater than the opportunity to just “think about something.” At the highest level, a personal reflection is an intimate and high-minded conversation with our own self—a conversation that is focused on a particular subject, topic or idea. The personal reflection differs from the ramble because it refuses to jump from thought to thought. Like a ramble, it retains the “I” in the voice; however, it stays fixed on a theme that is expressed in some kind of thesis or guiding statement. It is, by nature, less formal than a topical essay by retaining a spontaneous and unaffected narrative flow that feels to the reader like it is coming directly from your heart. It always has a distinct beginning, middle and end, but it never loses the sense of an open and inquiring mind on a search for truth—and every one appreciates someone who is willing to explore their own assumptions. I often tell my students that a reflection explores the question, while an essay answers the question. A personal reflection asks of each of us: Why am I writing this? What am I writing about? What do I think about my topic? If I come to a conclusion, how did I get there? A well-written personal reflection is as powerful as writing can get; it is the best of your mind offered to the reader—like a gift that the reader can share in, think about, and agree or disagree in equal measure. A personal reflection is the best of your thoughts distilled into an experience of words! 8. Literary Reflections: Writing without reading is like an egg without a yolk; the nutrients are there, but the flavor is lacking. Usually, when we finish reading something, we put it away on the shelf and convince ourselves we are impressed, amazed, indifferent, or profoundly moved. The literary reflection is an offshoot of the personal reflection because it does not try and criticize a writing piece solely on its literary merits, but rather it “talks” about something you have read purely on an emotional and intellectual personal level. There is almost no reason to write a literary reflection about something which you didn’t like reading. (That is what a “Review” is for!) Write Literary Reflections about literature that you feel is important for other people to read because you want them—your readers—to experience the same magic that you experienced. It’s like being on a sightseeing whaling boat and someone shouts out “There’s a whale,” and everyone turns to see the whale for himself or herself! They all appreciate your attentiveness, and in turn, you are pleased to point out the magnificence of the moment to them. 9. Reviews: One of the cool things about being in a writing community with your peers is the chance to write about and read about a whole assortment of books, movies, places, games and any other activity people your age love to do. We live in a world of reviews. We avoid movies because they get panned in the Boston Globe. We refuse to eat in a certain restaurant because it only has a three star rating in Gourmet Magazine. What many “reviewers” fail to realize it that what they write directly impacts a person’s very livelihood. The main job of a review is to tell your reader whether or not what you are reviewing lives up to the hype. If somebody is arrogant enough to say they are the best in town, then by all means, hold them to that standard. But if Al at Al’s Diner says he sells cheap burgers, it is up to you to tell us just how cheap his burgers are—and you might want to add in that you get what you pay for. I love reading reviews, but I insist they be honest and fair. Use common sense when writing a review: don’t give away the plot and ending of books and movies; don’t write a review about something someone else can’t experience. (That is what a personal narrative is for!) Make sure to balance out your reviews. If your reviews are all negative, you will soon get the rep as a negative guy; if your reviews are always positive and glowing, people will think you live in la-la land. 10. Expository & Persuasive Essays: Everyone likes to be right, and expository and persuasive essays are the perfect vehicles to define what is—and what is not—right and true! The word essay comes from the French word, “essai,” which means “to try.” A good essay tries to defend a certain point of view (called the “thesis”) using logic and supporting facts, not merely personal opinion. You can’t say in an expository essay that the 2008 Celtics are the best team in history because they make you feel good about yourself (great for a personal reflection) but you can say they are the best team in history because the Celtics are the first team to go from last in the league to champions in a single year! You can’t try to persuade me that eating kale is good for me, unless you provide proof that it will work for me as well as for you. It is certainly okay to write from your personal point of view (though in these kind of essays most teachers frown upon the “I” voice) but be sure that your points withstand the universal test of facts and science; otherwise, there will be no compelling reason to believe you! 11. Multi-Media: When I first wrote this list, it was titled “The Top Ten Writing Genres.” (I have always been a fan of “Top Ten” everythings!) But now I have to make an exception and create the Top Eleven list because the ability to create multi-media posts has gone from incredibly hard and frustrating a few years ago to unbelievably easy and fun to do now. Muti-media can include videos you have made, photo albums and galleries, podcasts, and screen-casts–and even TV shows and newscasts—and all of it possible to create on your iPad, phone or tablet.

Workshop Rubrics & Resources…

Workshop Videos…

How To Write a Narrative Paragraph

Write Better Sentences

The Narrative Paragraph Rubric

How To Create a Podcast

The Paragraph & Punctuation Power Workshop

Contact Fitz

Workshop Rubrics

Word Docs…

Sentence Building Exercise P&P Fitz Style Journal Entry P & P Narrative Paragraph Rubric PDF’s… Sentence Building Exercise P&P Fitz Style Journal Entry P &P Narrative Paragraph Rubric Use Quip… Writing Exercises Personal Reading Response Narrative Paragraph Rubric More Links… Join Quip! Rubrics & Resources JohnFitz.com The Elements of Style Classic Short Stories Balladmonger Poemminer

Listen to some songs…

Superman

Winter in Caribou

Trawler

James Joyce

Better pass boldly into that other world, in the full glory of some passion, than fade and wither dismally with age.

Henry David Thoreau

Write often, write upon a thousand themes, rather than long at a time, not trying to turn too many feeble somersets in the air–and so come down upon your head at last. Antaeus-like, be not long absent from the ground. Those sentences are good and well discharged which are like so many little resiliencies from the spring floor of our life–a distinct fruit and kernel itself, springing from terra firma. Let there be as many distinct plants as the soil and the light can sustain. Take as many bounds in a day as possible. Sentences uttered with your back to the wall. Those are the admirable bounds when the performer has lately touched the spring board. (November 12, 1851)

Workshop Two Curriculum

Paragraphing & Punctuation Units

Contact me if you would like to sign up for this course! Otherwise, feel free to use this workshop on your own.

Welcome to The Crafted Word Paragraph & Punctuation course. I really need to create a better name, but I don’t need to create a greater purpose because learning to craft good paragraphs and to punctuate effectively is the most critical skill a writer needs to practice and master.The P&P course (I like the short version of the name) is an eight-unit series of writing and reading workshops that focus on developing solid narrative writing skills, effective paragraph writing skills, and practical and easy to remember rules for punctuation—especially comma usage, which comprise around 90% of grammatical mistakes in the writing pieces I assess.

Welcome to The Crafted Word Paragraph & Punctuation course. I really need to create a better name, but I don’t need to create a greater purpose because learning to craft good paragraphs and to punctuate effectively is the most critical skill a writer needs to practice and master.The P&P course (I like the short version of the name) is an eight-unit series of writing and reading workshops that focus on developing solid narrative writing skills, effective paragraph writing skills, and practical and easy to remember rules for punctuation—especially comma usage, which comprise around 90% of grammatical mistakes in the writing pieces I assess.

Each unit should take around six-eight hours of time to complete in a thorough manner—maybe a bit more if you really dig into the content, perhaps less if you are already a fairly skilled writer and proficient reader. The basic format for each unit is similar and includes: sentence building exercises, blogging, paragraph construction, and punctuation skills study and practice. Additionally, I like to include at least one short minute meeting via Skype or private tutorial to assess and reflect on your experience with each unit and to help you through any difficulties you may have.

These are the units for Unit One…

- Writing Exercises: Complete the assigned writing exercises using the attached rubrics.

- Blogging: You need to write at least one blog entry for each unit using my rubric for creating a “Fitz Style Blog Entry” rubric and two journaling entries of your own choice, which can include video entries, reviews, podcasts, gallery photos, travel journals, etc. I will offer feedback on each of your entries. All of the assigned written work should be posted on your blog after all of the editing and revision is completed. In this way, you will start to build up a diverse and compelling digital portfolio.

- Narrative Paragraph Writing: The first unit is geared towards “writing about experience.” Complete the first Rubric-based paragraph: “The Power of Family.” You may complete this on your own using whatever word-processing program you wish, though my preference is to use the document sharing program, Quip.com that allows for more collaborative and ongoing feedback.

- Personal Reading Response: Read a short story from my Classic Short Stories website, and then write a personal reading response using the rubric for this assignment.

- Punctuation: Study and complete the punctuation packet for each unit. For Workshop Two, you should study Comma Rules 4-6. If you have an iPad or Mac computer or an iPad, I will send you a link to my Punctuation Workbooks on iTunes. All of my punctuation material is also available on my Punctuation website

- Final Reflection: Write a metacognitive reflection at the conclusion of your workshop.

Unit One: Blogging

Workshop Two: Blogging & Digital Portfolio

The Life of a Writer

Unit One Blogging Requirements: Three Posts

- Daily Journaling: Read the “Writing Genres” piece at the top of the page. Complete at least two journal entries using two of these genres and post to your blog. Use your blog as a place to practice the art of daily journaling. Feel free to write more–especially daily journal type entries–for the more you write without undue pressure, the better a writer you will become.

- Do your best to punctuate, paragraphing proofread as well as you can–but it does not have to be perfect. Writing in your blog should never be an exercise that fills you with anxiety, it should just be a place to write as freely as you wish. For Unit One, you should write at least two daily entries.

- Fitz Style Entry: Use my rubric and create at least one “Fitz Style Blog Entry.” The Fitz-Style entry is a rubric-based approach to creating a casual journal entry that looks great, flows like a good essay, and captures some part of your life in a more disciplined way than a simple journal entry.

Upload a Word Doc Rubric

Upload a pdf version

Use Quip!

You may share your journal entries with me on Quip before posting, and I will help you edit and proofread your post before you publish to your blog.

Unit Two: Writing Exercises

Writing Exercises

How To Write Better Sentences

Exercise #1: Adding Detail: One of the most common problems with sentences is that they just don’t tell the reader enough or give enough detail so that the reader feels informed and edified after reading the sentence. In the same way that any writing piece should always cover who/what/when/where/why, so should sentences—whenever possible. In many cases, this information might be in the sentence before or after, but it is certainly good practice to incorporate who/what/when/where/why into your sentences. Below are two simple rules for helping to make your sentences more informative, detailed, and interesting to your readers. Prompt: Write five sentences that include at least three of the who? what? when? where? and why? Details. The order of who/what/when/where/why is not important. Put the details (who, etc) within parentheses in bold. e.g. The young soldier struggled all night (when) through the jungle (where) to reach his base camp before the enemy could reach him (why). Post these sentences in the dropbox for this assignment.

- Put your sentence here

- Put your sentence here

- Put your sentence here

- Put your sentence here

- Put your sentence here

Exercise #2: Adding Imagery and Action: It is our job as writers to spark our readers’ imaginations! A lot of writers forget that their readers are not “in their heads.” The readers can’t “see” anything that is not “specifically” described. Simply saying, “It was a cold day” can mean something completely different depending on the time of year or place on the planet. So, as you write, be conscious of your readers, and be sure to give them the needed imagery and actions to make your thoughts become more real to your readers. Use specific imagery and actions to make these sentences more image rich. • e.g. Ginny ran into the house. Ginny ran into the house like she was late for a date. (I used a simile to create an image) • e.g. The red car pulled out of the driveway. The classic red Mustang convertible squealed out of the driveway and onto Birch Street. (I added descriptive adjectives and more detailed images and action.) Now do the same for these sentences: Post these sentences in the dropbox for this assignment.

- The tree fell in the woods.

- The plane flew through the sky

- I am not feeling well today.

- The baseball game was fun.

- I like ice cream.

Upload Word Doc

Sentence Building Exercise (Unit One)

Use Quip!

Unit Three: Narrative Paragraph Writing

Narrative Paragraph Rubric

The Power of Place

Moreover, I, on my side, require of every writer, first or last, a simple and sincere account of his own life, and not merely what he has heard of other men’s lives

~Henry David Thoreau

So, here is my formula for writing a good descriptive narrative paragraph. The rubric is slightly different than the rubric in Workshop One, so be sure to study the rubric before writing. This rubric is designed to help writers write more descriptively when writing about the power of a “place.” . In a narrative paragraph, a writer writes from a personal point of view about something “worth writing about” in his or her life. You should also view the videos on “How To Write a Narrative Paragraph” and “How To Use the Narrative Paragraph Rubric.”

Upload Rubric as Word doc P & P Descriptive Paragraph Rubric

Upload PDF Version P & P Descriptive Paragraph Rubric

Use Quip! Access shared Quip document

Which version should I upload…

I have always been a big believer in using the text editing program that you like best. I have my own opinions–as I am sure you do, too! To that end, you have several options:

- If you upload the word doc, it works (of course) with Microsoft Word, and this document can also be opened in Pages (my editor of choice–especially if using an iPad). It will also open in Google Docs, Open Office, and several other popular text editors.

- Use Quip if you want to work on a shared collaborative document, which I do recommend if taking the workshop. Quip takes a little getting used to using, but it works amazingly well on any browser, tablet, or phone. It is similar to Google Docs, though I like the collaborative tools better in Quip–and I really love the clean and uncluttered interface–plus, I am doing some of my teaching in China, which does not allow Google anything right now. But if you are a Google sort, then it is certainly your choice to go Google.

- Upload the pdf if you want to print a hard copy to work with when away from a computer or if you want a version that can be uploaded to your iPad or Kindle as an ebook.

- All of The Crafted Word Rubrics are also located on the Resources and Rubrics page.

- If worse comes to worse, simply copy and paste the rubric directly from this site into the text editor you prefer to use.

Explore the rubric…  This rubric breaks a paragraph down into three areas:

This rubric breaks a paragraph down into three areas:

- The first part of the paragraph introduces and narrow downs a theme from a broad theme (interesting and catchy enough to anyone) to a more narrow and focused theme that a writer can explore and explain in a single paragraph of 350 words or less, (but seldom less than 250 words).

- The central part of the paragraph (the setup and smoking gun) focuses on introducing and describing the experience that captures the essence and importance of your theme in a series of images and actions that tell the who, what, when, where, and why of the experience. (This is similar to text support or facts in expository or analytical writing). It proves the author has the authority and enough experience to write about this theme from the point of view of someone who has lived through the experience—and now has a story to tell that is meaningful, memorable—and above all, written with real and natural narrative voice.

- The last third of the paragraph (the head & heart and the conclusion or transition) explicates (which means to explain in detail) how the theme works within the experience the author just described. In the diagram you can see how the triangle starts small (narrow) and expands back towards a solid base. In practice, the writer should focus first on the parts of the experience that show the theme in action. Towards the end of the paragraph, the writer can (he or she does not have to) write about the importance of the theme in a more universal way.

- The closing line or transition will either be a brief and pithy conclusion or a sentence that transitions to a new paragraph that is logically linked together with the paragraph just completed.

NOTES Read each section carefully to be sure you are following the flow of the rubric. A narrative writing piece needs to have the natural flow of human speech to be effective. If it is too choppy, it will be an ineffective piece because it won’t feel or sound real. Remember that no writing piece is ever “done.” It is abandoned, and every minute before that time is a good time to “change” your paragraph for the better. Before you abandon this piece, let it sit for a couple of days, then go back to it with fresh eyes and a fresh mind and do what you need to do to make it more perfect—at least in your mind. This rubric, if used wisely, is essentially a brief essay—and a damn good one if you give it the time and focus that well-crafted writing needs. Paragraph Prompt: The Power of Family

No matter how a family is created, it is, for better or worse, the most universal theme and common thread that binds us all together as humans. Every family develops its own dynamic, their own way of doing things that they borrowed from traditions, religions, cultures, and often trial and error; but the basic fabric of a family is the same the world over—it is a group of people who are somehow brought together and figure out what it means to be a family.

Think of your own family and use this rubric to write a one paragraph reflection on some aspect of your experience with your family that illustrates the theme of the power of your family in a single experience in your life.

STEPS OF THE RUBRIC: Read each section carefully and try to follow all of the steps of the rubric. Read each section out loud or use text to speech and proofread carefully. A narrative should “sound” just like you would speak. Except better. 1. THE MAJOR THEME: Writing out your theme as a single word or short phrase is a good way to help keep focused as you write the paragraph. Put your one word or short phrase theme centered on the page. It should constantly remind you that THIS is the theme you have to stay focused on throughout your paragraph! The Power of Family

[Put your theme here]

2. GUIDING QUOTE: If you are only writing a single paragraph, I think it is a great idea to put a quote above the paragraph that captures the mood, tone, and theme of your paragraph. For example: if I wish to write about the power of family, I could use a quote like this, put in italics, with the author’s name below the quote. Home is where when you get there, they have to let you in. ~Robert Frost [Put your text quote here] 3. BROAD THEME: Write a short declarative statement that touches on a broad theme that all of us can relate to in some way or other. This acts as a “hook” that will attract your reader’s attention. Despite what you might wish, no one really cares about you when they read; a reader cares primarily about himself or herself. This broad theme is a theme that almost any person can relate to on some level, and hopefully it is intriguing enough to make your reader want to read on. Do not mention you or your family in this sentence! For example: if you want to write about the importance of family, here is an example of a broad theme:

- It is only our immediate family that gives us unconditional love.

[Put your text here]

4. NARROW THEME: Narrow down your theme by writing a phrase or sentence using the theme word that captures how your chosen theme is used in a specific way in the experience you are going to write about. Make sure it is “clear, concise and memorable” because this is what you want your readers to remember “as” they read your paragraph. This is the sentence that “steers” your reader in the direction you want your paragraph to go, and in that sense, it is what your paragraph is going to be about. YOU should be in this sentence; otherwise a reader may be misled into thinking you are merely writing about the importance of the theme, not about an experience you have had. For example:

- It was my family that I turned to when I had no place left to go.

[Put your text here]

5. ONE/TWO PUNCH: Follow your topic sentence with one or two more sentences that add detail or explanation to your topic sentence. These sentences can (and maybe should) be longer sentences. This helps to “narrow down” the focus of your paragraph so that you only have to write what can be fully explained in one paragraph. For example:

- When I was alone in the world; when nothing was going my way, I knew that the door of family would always open always open for me and welcome me back into the arms of those people who love me without reservations.

[Put your text here]

6. SET UP: The setup is the lead-in to your smoking gun. It prepares your reader for the description of your experience in the smoking gun by giving context to the experience.

- Who is there?

- What is happening?

- When is it happening?

- Where is it happening?

- Why is it happening?

[Put your text here]

7. SMOKING GUN: When writing about a personal experience, chose a specific personal experience (or even a smaller part of an experience) that explicates, illustrates, and amplifies the theme of your paragraph. This personal experience is proof that you have been there and done that, which is why we call it the smoking gun! It is evidence that you are the one who had the experience that only YOU can write about with full authority. When you write the smoking gun, be sure to include as much detail as needed—the who? what? when? where? and why?—to fully capture the theme of your paragraph. For example:

- At no other time in my life was this more obvious than when I returned to my family home in Concord after a long journey to the China to discover the essential truth about life. Broke, disheveled, and disenchanted, I stood on the doorstep and tentatively rapped on the door. No smile was wider than my mom’s; no arms were wider than my dad’s as they pulled me into their arms and into the living room I left so long ago.

[Put your text here]

8. HEAD & HEART: Show your reader your thoughts! Write as many more sentences as you “need” (but at least three more) to illustrate and elaborate upon whatever you introduced in your theme-setting sentences. This is where you reflect upon your experience and describe the ways that your experience reflects your broad and barrow theme. For example:

- It didn’t matter that I left home without even telling them where I was going. It didn’t matter that I had once criticized their lives as dull and meaningless, and it didn’t matter that I never called and never wrote. It only mattered that I was home again with my family.

[Put your text here]

9. GET OUT or GO ON! This sentence either wants to close out your thoughts or “transition” to a potential new paragraph. For example:

- For me, it only matters that I will never turn my back on my family again because when times are tough, family is all that really matters.

[Put your text here]

10. Copy and Paste Completed Paragraph Here: In sit amet nulla semper, sodales eros vel, porta dolor. Aenean tincidunt accumsan tortor ut scelerisque. Nunc interdum risus eu magna consequat, eu elementum nisl commodo. Curabitur ut ullamcorper mi. Pellentesque quis suscipit metus, vel lobortis nunc. Duis semper neque et libero fringilla, euismod tempor lacus dignissim. Morbi nec dui ipsum. Nulla quis pellentesque erat. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Mauris eget ex diam. Phasellus eu justo eu tortor convallis lobortis.Duis non dignissim sem. Etiam accumsan gravida fringilla. Morbi lacinia malesuada posuere. Vivamus posuere tortor risus, ut placerat orci interdum commodo. Aliquam nec molestie quam, pharetra luctus orci. Nullam non finibus turpis, quis euismod quam. Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Cras vehicula augue quis lectus lacinia, sit amet fermentum massa condimentum. Praesent pulvinar est lacus, sit amet mattis sem pretium eu. Sed nec bibendum erat. Curabitur vitae lorem felis. Nullam mauris nibh, consectetur a tortor non, interdum porta nunc. Quisque elit justo, volutpat ut hendrerit vel, mattis in mauris. Etiam risus quam, volutpat eu augue sed, posuere pellentesque lectus. THE POTSAID RULE OF THREE: Proofread, Edit, Revise, & Submit

- Literature is abandoned, not finished! Go back and re-read what you have written.

- Find three areas or sentences that you can make better. If you can’t or won’t do this, then you are light years away from being a writer.

- Often you can find a better broad or narrow theme sentence somewhere else in the paragraph. You can almost always find a more clear and effective way to write a sentence than you wrote on your first try.

- If the rule of three was too easy (meaning you easily found mistakes) do it again…and again if you have to.

*When you are convinced you have done all you can, submit your final review as required by your teacher or editor.

Unit Four: Personal Reading Response

Personal Reading Response

How To Write a Literary Reflection

I am sure that many of you have been asked to do in-class or summer reading of some sort—and I bet, too, that your teachers will ask you to write something about a book, poem or story—or even just a chapter—that you have read. My Personal Reading Response Paragraph Rubric can help you write an awesome and meaty paragraph that is insightful, well-organized, and interesting. Try it! A personal reading response needs to feel and sound like you speaking at your very best, and it needs to be both honest and thoughtful. Being thoughtful means that you are careful and considered and real in your writing. Being honest means being authentic. Genuine praise is enlightening to a reader; false praise reeks of arrogance. You can use this rubric when you are asked to—or desire to—craft a “personal” response to a piece of literature. Read the descriptions of each step of the rubric on the left side, and then insert your sentences into the boxes on the right side of the rubric. When you are completed, paste the full paragraph below the rubric. Your completed response should be between 300-500 words. 1. Assignment Details:

- Follow all of the formatting requirements .

- Follow the directions for each step of the rubric.

- Be sure to “try” and match what you write with the directions for each stage of the rubric.

2. The Broad Theme (Opening Paragraph) The Hook Every writing piece needs a good and pithy “hook” to gain and grab the readers attention.

- Without even mentioning the title, write a brief, single sentence that tries to capture the attention of your audience by stating the major theme of your personal reading response.

- The way you craft this sentence sets the direction, tone and mood of the reflection that follows.

[Insert your text here]

3. Narrow Theme: (Opening Paragraph) Get Specific

- In the second sentence, introduce the piece of literature, the genre of the piece, and the author, as well as the major effect the writing piece had on you personally.

- Remember that book titles are italicized.

- Short story, song, and poem titles are put in quotes.

[Insert your text here]

4. One/Two Punch: Opening Paragraph What is the Author Trying To Do? Every writer writes for a reason, and when doing so he or she tries to get the reader to feel or think in a certain way.

- Write two or three more sentences that tells your reader what “you” feel the author is trying to do in the writing piece.

- For added emphasis and support, you could also include a researched quote from another source to back up your thoughts.

[Insert your text here]

5. Smoking Gun: (Second Paragraph) Summary & Text Reference Briefly, using three to five sentences, summarize the story, poem, or song. It is important to give a brief summary of the writing piece because it helps your reader put the writing piece in context. This does not mean, however, to give away all of the details and spoil it for your reader.

- Who: who is or are the major characters?

- Where: where is the action happening?

- When: when is the action taking place?

- What: what is the main conflict that is happening?

- Why: why is this conflict happening?

[Insert your text here]

6. Head & Heart: (Third Paragraph) Metacognition Remember that in a personal response, you can’t be wrong―as long as you are truthful. In this section of your paragraph write honestly from your head and heart about your experience reading and understanding the text. Below are some ideas for how to approach this paragraph, but please expand the list to suit your response. Here are some ideas, but don’t answer these like a list of questions! Weave them into a narrative paragraph that flows “conversationally.” You can’t be wrong here, but you can write in a way that is dull and boring to your readers.

- How did the writing piece affect you? Was it exciting, boring, interesting, dull…why?

- What emotions did it make you feel?

- Did you relate to the content or the characters in some way, shape or form?

- Did it challenge you to think and feel in a different way?

- Did it change any part of your own world view?

- Did it bring up memories of other books or authors you have read?

[Insert your text here]

7. Get Out: Fourth Paragraph Elevator Review Conclusion The conclusion is as important as the hook, so do your best to make the end of your paragraph as interesting and refreshing as your opening sentence.

- Imagine that someone in an elevator asked you about what you are reading, and you only have ten seconds to respond.

- You can touch on what you have already written, but don’t use the same words again.

- Really, it should not take more than ten seconds to read this last paragraph!

[Insert your text here]

8. Paste, Proofread & Publish Do What Writers Do Paste each step of the rubric in the space below. Proofread, edit and revise as needed. Publish as required by your instructor.

- The rubric is a guide, not a rigid structure. If it sounds too academic it will lose the power of a narrative essay.

- Revise your sentences and paragraphs to create a narrative voice that mimics your real voice.

- Pay close attention to formatting, punctuation, grammar and mechanics.

- Add more paragraphs if you feel it will be more effective for your readers.

- Have fun with your words, and your readers will have more fun reading!

[Insert your text here]

Unit 5: Punctuation

Punctuation

Comma Rules 1-3

Study the punctuation rules below and complete the assigned quizzes and exercises. If you have an iPad, you may download my book “Fitz’s Top Ten Comma Rules” and use that as an interactive approach to learning the major comma rules.

Comma Rule #4: Parenthetical Elements

Parenthetical Elements

Things to know…

- Parenthetical elements are words and phrases that add detail to a sentence, but which are not “essential” to an understanding of the sentence.

- A parenthetical element is a non-essential element, meaning it “could” be enclosed in parentheses and left in the sentence, or it could be removed from the sentence.

- If you want your reader to read the parenthetical element without emphasis, use commas.

- If you want to whisper or say something as an aside, use parentheses.

- If you want to shout or add a lot of emphasis use double dashes to enclose the element.

Parenthetical elements are words and phrases that add detail to a sentence, but which are not “essential” to an understanding of the sentence.

- I heard his car, clanging and banging like pots and pans, coming down the street. [“clanging and banging like pots and pans” is added detail that is not necessary to understand the sentence. It is simply a phrase that adds vivid, but not essential, detail.]

A parenthetical element is a non-essential element, meaning it “could” be enclosed in parentheses and left in the sentence, or it could be removed from the sentence.The kid in the back row, who loves grammar, took all of the quizzes and studied the comma use web page. [The parenthetical element is included in the sentence]

- The kid in the back row took all of the quizzes and studied the comma use web page. [The parenthetical element is NOT included in the sentence

If you want to whisper or say something as an aside, use parentheses. ~The kid in the back row (who loves grammar) took all of the quizzes and studied the comma use web page. If you want your reader to read the parenthetical element without emphasis, use commas. ~The kid in the back row, who loves grammar, took all of the quizzes and studied the comma use web page. If you want to shout or add a lot of emphasis use double dashes. ~The obnoxious kid in the back row—who loves grammar—took all of the quizzes and studied the comma use web page!

#2: Commas with Coordinating Conjunctions

Things to know…

- So, yet, and, or, nor, for, and but are the seven coordinating conjunctions

- A comma and a conjunction can always be replaced with a period or semi-colon instead of the comma and conjunction.

- Soyet Andor Norforbut only work as conjunctions if they are connect two or independent clauses together

- If the sentence is brief, a comma is not required before the conjunction

Commas with conjunctions must have an independent clause (meaning, the clause can stand alone as a sentence) BEFORE and AFTER the conjunction and comma.

- e.g. I need to buy a new computer, so I am going to the mall.

- e.g. It is a cold day, yet it is a beautiful day on the mountain.

- e.g. Sally is happy today, and she is feeling better.

- e.g. I am either going to climb the mountain, or I am going to die trying.

- e.g. I am neither talented, nor is there a place for me on the team.

- e.g. Do not show up at my house, for I am not going to be home today.

- e.g. I am not a good basketball player, but I am an amazing baseball star.

A comma and a conjunction can always be replaced with a period or semi-colon instead of the comma and conjunction.

- It is raining, so I am not going to school. [comma and conjunction]

- It is raining; I am not going to read. [semi-colon]

- It is raining. I am not going to study comma usage. [period]

Soyet Andor Norforbut only work as conjunctions if they are connecting two or more independent clauses together to create a compound sentence; otherwise, they are being used in different ways.

- e.g. You are so cool! [Here “so” is being used as an adverb]

- e.g. I am not done, yet. [Here yet is being used as an adverb that indicates time.]

- e.g. I play soccer and tennis in the summer [Here “and” is being used to connect a series of two items]

- Here are some more example where a comma is “not”needed:

- e.g. I don’t like fish or fowl.

- e.g. I don’t like swimming nor sailing. [Here nor is being used as a conjunction to negate the ???

- e.g. Finally, my car is for sale!

- e.g. She loves everyone but me.

If the sentence is brief, say eight words or less, it is perfectly fine to leave out the comma as there

- e.g. I don’t want to and you don’t want to!

- e.g. Give it back or you’ll regret it.

- e.g. She’s pretty but she’s not happy.

- e.g. Give me some money so I can go!

#3: Commas with Introductory Elements

Introductory Elements

Things to know…

- An introductory element is any word, phrase or dependent clause that comes before the main independent clause of the sentence

- Introductory words are usually names, adverbs, salutations or interjections

- Introductory phrases set up or place in context the main clause of the sentence, and so are usually prepositional or adverbial phrases

- Introductory clauses are always dependent because the clause contains a subject and a verb, but it is not a completed thought

An introductory element is any word, phrase or dependent clause that comes before the main independent clause of the sentence.

- Introductory words are usually names, adverbs, salutations or interjections

- e.g. Actually, Fred can take the test. [introductory adverb]

- e.g. Fred, be careful taking the test. [introductory name]

- e.g. Oh, Fred should be careful taking the test. [interjection]

- Introductory phrases generally act to set up or place in context the main clause of the sentence, and so are usually prepositional or adverbial phrases.

- An adverbial phrase simply modifies some sort of action (a verb) by telling a reader:

- when some action happened

- where some action happened

- how some action happened

- how much some action happened

- e.g. Without thinking, he ran into the burning building and saved his goldfish. [This is an adverbial phrase: the word without modifies the verb thinking]

- e.g. Before dinner, I plan on taking a nap. [This is a prepositional phrase: the word before modifies the noun dinner]

- as far as comma usage goes, knowing whether the phrase is a prepositional phrase or an adverbial phrase does not really matter.

- All that really matters is that you–the writer–reccognize the phrase as a phrase introducing and/or modifying the independent clause that likely follows.

- whether or not the comma is “needed” can be the choice of the writer depending on if you want the reader to pause at that point in time.

- e.g. Without a second thought he saved his goldfish.

- Only a fool or a pedantic old teacher would be perplexed by the lack of a comma in this sentence.

- Introductory clauses are always dependent or subordinate clauses (different name for essentially the same thing) because the clause contains a subject and a verb, but it is not a completed thought. To muddy the water even further, some folks call these clauses restricted or unrestricted clauses.

- e.g. Because it is snowing, I am not going to school.

- e.g. After the snow falls tonight, school will surely be canceled tomorrow.

- e.g Provided our headmaster is a wise man, we will surely get the day off tomorrow

- e.g. Since you don’t seem to care, we will have school tomorrow!

- A dependent/subordinate/restricted clause always has a “word” before the clause (marked in red in the example). This is often called the dependent marker word.

- Below is an incomplete list of possible dependent marker words introducing a dependent clause:

- rather, even though, once, whenever, although, until, if only, whereas, as long as, because, before, as if, after, whether, etc…

[cap_iframe_loader type=’iframe’ width=’100%’ height=’600′ frameborder=’0′ src=’http://www.thecraftedword.org/wp-content/uploads/adobe_captivate_uploads/Dependent_and_Independent_Clauses2/index.html’]

Punctuation Quizzes & Exercises

The punctuation quizzes and exercises for Workshop One will be posted in here.

Unit Six: Metacognition

When you finished all of this work, write a metacognition of at least 300 words using the narrative paragraph rubric to help guide the structure and flow of this reflection on your experience. Post the finished reflection to your blog. And you’re done. Congratulations. It is time to move on the next workshop.

Check out some more Crafted Word Offerings…

The Crafted Word Blog…

Remember the Time

Write what you know. ~Mark Twain I don’t always practice what I preach, especially when it comes to the simple, unaffected, and ordinary “journal entry.” Much of my reticence towards the casual journal entry is the public nature of posting our journal writing as...

Remote Learning 2.0

Explore, Assess, Reflect & Rethink How to move on to a better tomorrow... For most of us teachers, our first crash course in remote learning is done, and the wise work now is to separate the wheat from the chaff and truly assess what works and what can be...

The Farmer, the Weaver & The Space Traveler

Words matter. Words carefully crafted and artfully expressed matter infinitely more. There is something compelling in a turn of phrase well-timed, arresting image juxtaposed on arresting images; broad ideas distilled into clear, lucid singular thought. For the...

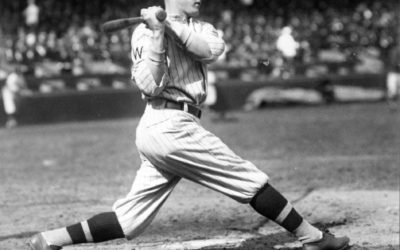

Swing, dammit, swing…

What’s so important about this literary analysis paragraph thing? Maybe you won’t be spending your life analyzing literature. Maybe this is some academic exercise that is ultimately no big deal in the greater scheme of your life.Or maybe it is…You will always be...

Embrace the Beast

The Rules of Punctuation If you don’t use it, you lose it... ~Fitz What do you really need to learn? What teaching and what practice will help you learn what you “really need to learn” in a way that will somehow stay with you and be useful and necessary to...

Ten Tips for a Great Narrative Essay

So much depends on the red wheelbarrow glazed with rain water beside the white chickens. -William Carlos Williams It was funto be swimming and clambering around with my kids yesterday in a remote stream in the Berkshires and thinking: "This would be a cool...