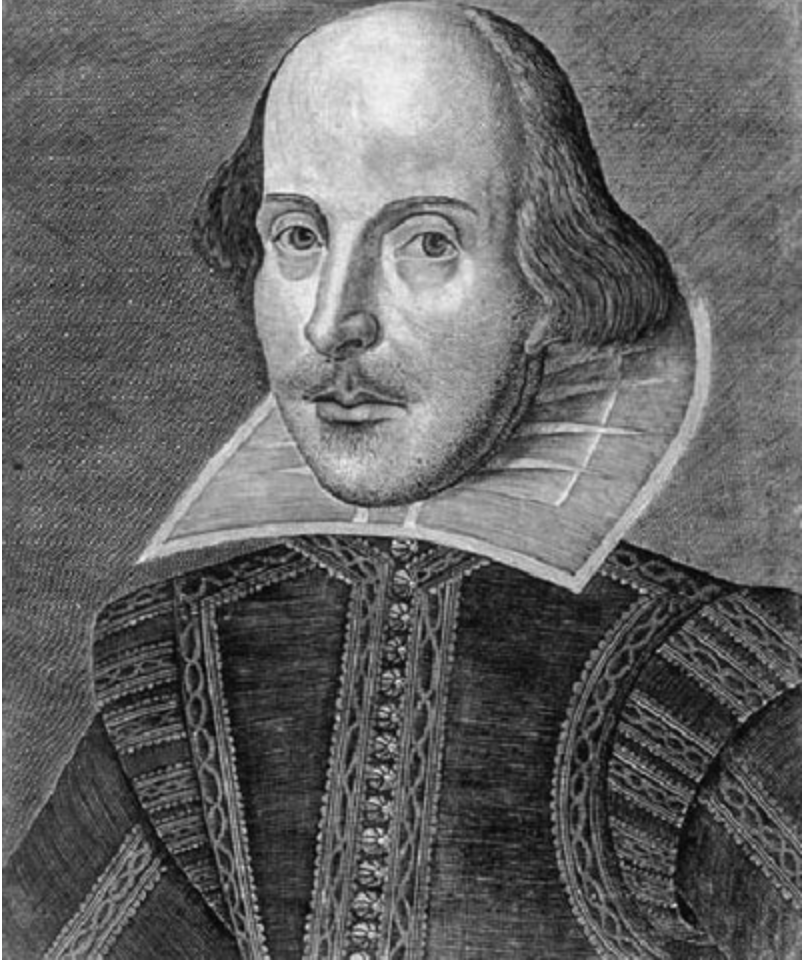

How to write a shakesperian Sonnet

You might be the next Shakespeare. Write a sonnet!Terms to know:

- Iambic Pentameter

- Iamb

- Quatrain

- Couplet

- Rhyming Couplet

- Sonnet

- Meter

- Metrical Line

- Scansion

- Foot

Download The Rubric PDF

It is a cruel task master who asks his or her students to “do” what he or she has not done themselves—and so it is with the writing of strict sonnets—but it is a task I will also undertake if only to know the difficulties I am forcing upon you. After years of coaching football and wrestling, it is all too obvious to me that lazy practices make for lazy athletes. By the same logic, tough practices make for better (though not necessarily happier) athletes. Writing a good sonnet is going to be a tough practice—for me, too. I have written “unrhymed sonnets” (See below) that follow the thematic and metric structure of sonnets, but I have only written a few classical Shakespearean or Italian sonnet. The one I include here I wrote for Mrs. Ward’s retirement celebration.

Sooo, what is a sonnet? In writing sonnets, the emphasis is placed on exactness and perfection of expression. A sonnet, the way I am first teaching you [Shakesperian Sonnet as opposed to the Italian Sonnet, which came first)], is a fourteen line poem that is written in “rhymed, iambic pentameter,” meaning it has three rhyming “quatrains” [four lines of poetry] followed by a single rhyming “couplet.” [two lines of poetry, usually with the same rhyme]. (See how I am able to get in all of my fun poetry vocabulary!)

Other more modern poets use different rhyme schemes to write their sonnets, but all adhere to the basic fourteen line model. What is cool about sonnets is that it forces a poet to be incredibly precise with their language, and it creates a brief and melodic form of poetry that is pleasing to the ear, enjoyable to read, and which deals with some great philosophical truth that all people can (or should be) able to relate to on a deep emotional and intellectual level.

Here, a picture is worth a thousand words:

We’ll use Shakespeare’s Sonnet XXIX

Sonnet XXIX

When in disgrace with Fortune and men’s eyes, (A)

I all alone beweep my outcast state, (B)

And trouble deaf heaven with my bootless cries, (A)

And look upon myself and curse my fate, (B)

Wishing me like to one more rich in hope, (C)

Featured like him, like him with friends possessed, (D)

Desiring this man’s art and that man’s scope, (C)

With what I most enjoy contented least, (D)

Yet in these thoughts myself almost despising, (E)

Haply I think on thee, and then my state, (F)

(Like to the lark at break of day arising (E)

From sullen earth) sings hymns at heaven’s gate, (F)

For thy sweet love remembered such wealth brings, (G)

That then I scorn to change my state with kings. (G)

~Shakespeare

Like a lot of people, your first response may be, “I have no clue what Shakespeare is writing about—something about being a king, maybe…” So, it takes a bit more digging, deliberating, thinking and mind-opening to understand that this sonnet is about how being in love (and simply remembering that love) trumps everything and makes a person forget how or her woes and sorrows and his or her misfortunes and jealousies and makes him or her happier and wealthier than any king—and unwilling to change places with anyone on earth.

And that is pretty cool and powerful!

Understanding Poetry

To understand a poem, deconstruct it and analyze how the poem is “put together.” (Kind of like that TV Show “How Things Work.”) This deconstructing is called “scansion” because you are literally scanning the poem to see if there is a pattern that creates the “sound” of a poem. Of course, there is more to scansion than that, but for the here and now that is our definition.

Now, use my rubric (actually, it is probably Shakespeare’s rubric) and create your own sonnet!

1. Notice the rhyme scheme of the poem:

a b

c d c d

e f e f

g g

The first three rhyme patterns are in quatrains (four lines). The last two (GG) are a

2. Notice the meter of the poem:

Each line of poetry is written in iambic pentameter: Five ba-booms per line (or five unstressed/stressed “feet” in real poetry terminology) basically equaling ten syllables per line–though there are some exceptions to this definition, such as when writing with a pattern of two unstressed syllables followed by a stressed, which is called an Anapest.

For example…

Sonnet XVIII

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate:

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer’s lease hath all too short a date:

Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,

And often is his gold complexion dimmed,

And every fair from fair sometime declines,

By chance, or nature’s changing course untrimmed:

But thy eternal summer shall not fade,

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st,

Nor shall death brag thou wander’st in his shade,

When in eternal lines to time thou grow’st,

So long as men can breathe, or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

3. Notice the Thematic Development of the poem:

The thematic development is how the story of poem unfolds. Ultimately, this is left up to the writer, but in traditional

First Quatrain:

Set the Scene and State the Theme:

Rhyme Scheme: ABAB

Use the first quatrain to set the scene and tone and to point your reader in the general direction your poem is going to go.(Similar to the broad theme and narrow theme in the paragraph rubric.)

Second Quatrain:

Show the Theme in Action

Rhyme Scheme: CDCD

Use the second and third quatrains to develop your theme by using real-life examples and descriptions or a deep reflection.

Third Quatrain:

Add a Cool Twist:

Rhyme Scheme: EFEF

Use the third quatrain to add a cool twist or to pose a conundrum—a seemingly unsolvable problem or dilemma—or a paradox, which is a statement that apparently contradicts itself and yet might be true…

Final Couplet:

Craft a Memorable Couplet

Rhyme Scheme: GG

Use this last couplet to create a profound and memorable statement that tries to capture the spirit, theme, and intent of the poem.

This is my Sonnet #3 that I wrote for Mrs. Ward, a beloved teacher at my school, which I recited at her retirement party.

The parting is the hardest part of fate—

The slow untangling knot still left unwound;

We pause as if the hour is too late

To divvy fair the treasure we have found.

Our words like fingers pointing at the moon;

Whose light reveals the shadows that you teach;

And this goodbye that seems to come too soon

The pulsing tide returns you to our reach.

With each soul you shaped the morphable clay

And lay to rest the fickle thorns of time;

You gave us all an ordinary day

Below some harsh summit we could not climb—

I never asked, but wonder how and why

You somehow manage to teach frogs to fly.

~Fitz

The sonnet form can and should be adapted to other forms of poetry.

Here is my unrhymed sonnet I wrote in in fourteen lines of blank verse, using five “ba-booms” for each line.

The Bottom Line

Around my cabin they are dropping trees—

the tall white pines that sentinel these woods,

that crack and thud before being dragged

to the landing, and then bucked and loaded

onto a top-heavy pile of harsh truck.

Every so often the machines will stop and I’ll hear the loggers

and I’ll hear the loggers gam and cuss:

“Ah, for Chris’-sakes, these have all got heart-rot.”

Pissed, probably, they went and bid so high

for what the mill owners will just laugh at.

The slash is piled high and the ground scarfed.

I dip my pen and turn back to my work.

Piecing together the best of our wood

none of us will make a killing today.

Explore more of The Crafted Word Rubrics