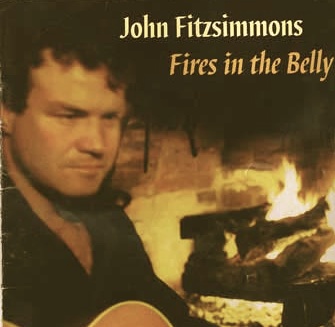

Fires in the Belly

Foreward

Foreward

When I first met John Fitzsimmons in 1989, I thought the Old Man of the Mountains had shaved off his beard, picked up a guitar, and was trying his luck as a folksinger. He was a bit late, covered with small pieces of dirt, and apologized tersely for his condition, saying he’d just finished building a stone wall for a neighbor. He shook my hand and I knew he wasn’t lying, but I wondered what kind of a man prepared for a recording session by handling rough boulders. Several hours, and now several years later, Fitzy still makes me wonder, but I find I’m more often amazed than amused.

His songs seem to come from deep within the New England earth. Sometimes burning with fire and rage, sometimes warm and gentle, but always honest and clear. In a voice that’s equal parts granite and brandy, John etches unsentimental portraits of real people facing life’s struggles and joys the only way they know how. Sometimes the characters manage to find some distant light, but it’s the journey, not the journey’s end, that’s important to John.

What makes this disparate collection believable is the road traveled by the writer. Over the past twenty years John has worked as a sailor, farmhand, logger, woodcarver, musician, storyteller, teacher, wrestling coach, and other jobs he refuses to talk about. For the past twelve years he’s held forth every Thursday night in the back tavern of the Colonial Inn in Concord, (once home to Henry David Thoreau’s family) and the place to go if you want to meet some real swamp Yankees, people who lived in these towns before the yuppie exodus made them suburbs. You’re sure to find these folks there: listening to the music, singing along, sucking down brews, and giving Fitzy a playfully hard time.

The other “voice” on this recording is the inspired production and musicianship of Seth Connelly, who plays far too many instruments far too well for a mere mortal. Seth has worked with John Gorka, Catie Curtis, Ellis Paul, Geoff Bartley and others: and when John hooked up with him a couple of years ago, these songs took on new colors and dimensions. they both share a complete trust in each others vision, as well as a friendship as strong as the songs they’ve created.

So I want you to listen to this friend of mine, John Fitzsimmons. His songs give voice to things we all can hear. Put this on, sit back, and hear for yourself…

Eric Kilburn

12/28/95

Joshua Sawyer

I doubt I’d ever have taken this road

had I known how fallen it really was

to disrepair: driving comically,

skirting ruts and high boulders, grimacing

at every bang on the oil pan.

I tell you it’s the old road to Wendell —

that they don’t make them like this anymore.

We’re bound by curious obligations,

and so stop by an old family plot

walled in by piles of jumbled fieldstone,

cornered to the edge of what once was field.

The picket gateway still stands intact,

somebody propped up leaning on a stick,

an anonymous gesture of reverence.

Only nature disrespects: toppling stone,

bursting with suckers and wild raggedness.

A gravestone, schist of worn slate, leans weathered:

Joshua Sawyer Died Here 1860

Another stone, cracked, has fallen over.

I reset the stone, and scrape the caked earth

as if studying some split tortoise shell,

and have keyed in to a distant birth —

His wife Ruth died young; so I picture him

stern with his only daughter, only child —

speaking for a faith which could defy her.

There’d be no passing onto when she died —

twenty-two, more words beside her mother.

Still these stones and fields you kept in order,

long days spent forcing sharp turns on nature,

accepting the loose stone and thin topsoil.

A Wendell neighbor must have buried you

whispering a eulogy which is as lost

as your daughter, your wife, and this farm:

—Joshua Sawyer

I’ve never been down this road before

I would like to speak with you of faith.

Don't You Ever Let Go of Your Soul

Sometimes yeah.

Sometimes no.

Sometimes it’s somehow somewhere in between.

Sometimes it’s somewhere that no one has been—

no, nobody, nowhere, no nothing can end.

So don’t you let go and hope you’ll find it again.

Don’t you ever let go—

Don’t you ever let go of your soul.

Don’t you ever let go of your soul.

Things they got ways

of slipping by unless you hold—

so don’t you ever let go

of your soul…

Sometimes, man I’d wish

there’d be snakes in the trees,

and I’d just keep this big space between them and me—

I’d say no way Jose’ that ain’t how I’ll be;

but between right and wrong there’s this large mystery;

it makes freedom so hard, so hard to be free.

Don’t you ever let go of your soul.

Don’t you ever let go of your soul.

Things they got ways

of slipping by unless you hold—

so don’t you ever let go

of your soul…

Sometimes when I hear that fate’s back in town,

and it’s working the strings of the prophets and clowns;

and you’re hung and you’re strung

and you’re brung and wore down,

and you hear, Fitz, man, don’t worry,

‘cuz here’s what we’ve found:

fate’s got a chance

when you’re soul’s out of town.

Don’t you ever let go of your soul.

Don’t you ever let go of your soul.

Things they got ways

of slipping by unless you hold—

so don ’t you ever let go

of your soul…

Somewhere North of Bangor

Somewhere north of Bangor

on the run from Tennessee.

Lost in back scrub paper land

in section TR-3.

It’s hit him he’s an outlaw

a Georgia cracker’s son,

who killed a man in Nashville

with his daddies favorite gun.

It’s hit him with the loneliness

of wondering where you are

on a long ago railway

stretched between two stars.

Two weeks shy of nineteen

in 1992,

she got tickets with her girlfriends

for that new band coming through.

She got tickets for the show,

she said, “go on and have a night on town.

I’ll meet you in the morning at

Frannie’s Coffee Ground;”

but she met a backstage roady

from that traveling country band,

and now it’s hard to slow the pain that grows

inside a hurtin’ man.

I took one of Joe’s old Rugers

and the law into my hand.

I borrowed Lance’s Mustang

and a Mobil credit card.

I drove every pot-holed backroad

they’ve got in Arkansas.

By now there was an all points

on a Georgia crackers son

who left on Sunday morning

with his daddies favorite gun.

I heard the church bells ringing, pleading,

pulling on my soul.

I almost turned back—I couldn’t bear to go.

Twenty years of praying

and doing what I was told.

They played three shows in Nashville

and Johnson City for a night.

Two air-brushed old greyhounds

under marquee neon lights.

I followed them to every show

until I found the man

with a tattoo of Geronimo

on the back of his right hand.

I asked him about a gal he met

at Saturday night’s show;

she says that you get kind of rough

and don’t understand no.

I thought that I’d find out myself

just if that be so.

I heard you like to think

you lead your life out on the edge.

You say the way we live our lives

we may as well be dead.

But now that you believe

that you’re the God of your own land

you’ve got to walk a higher road

than any other man.

You’ve got to toe a higher line

and somehow make it real;

you’ve got to learn in disregard

to think hard as you feel.

He pulled his knife,

I took his life—

you’ve got to pay for what you steal.

Now I’m somewhere north of Bangor

on the run from Tennessee.

Lost in back-scrub paper land

in section TR-3.

No more an outlaw

than a Georgia crackers son

you will not play the renegade

trapped or on the run;

and you love the strange wild loneliness

of knowing who you are—

you love the way the patterns lay

stretched between the stars;

and you know that when they find you

they won’t know who you are.

Shane

It’s been too long feeling sorry for myself.

It’s been too long with my life up on the shelf.

Sometimes wish that I was Shane—

shoot Jack Palance, and disappear again;

don’t have no one

don’t want no one

don’t miss no one…

living lonely with a saddle and a gun.

Some men just want to walk behind a plow.

Other men find a different way somehow.

Wish that I could be like Shane:

come this way once

and never come this way again;

don’t have no love

don’t want no love

don’t miss no love:

hell below and the stars above.

Shane, come back Shane.

Prairies dried up

it won’t rain.

You’re a technicolor cowboy I know

but I sure do hate to see you go.

Sometimes I look back and I wonder why

I can’t touch the ground or reach the sky.

Shane would come but he wouldn’t stay.

He’d empty his pistols and ride away;

don’t have no star

don’t want no star

don’t miss no star:

no destination is too far…

Shane, come back Shane.

Prairies dried up

it won’t rain.

You’re a technicolor cowboy I know

but I sure do hate to see you go.

It’s not easy living here this way.

I watch the sun come up and go down each day.

Sometimes it helps to ease the pain

to shout ‘Shane, come back Shane.’

don’t have no one

don’t want no one

don’t miss no one

not trying to undo what’s been done…

Shane, come back Shane.

Prairies dried up

it won’t rain.

You’re a technicolor cowboy I know

but I sure do hate to see you go.

*Written by Jimmy O’Brien ©

(I’ve sung this song so much that it feels like a part of my life. Thanks, Jimmy!)

Somewhere North of Bangor

I know your name. It’s written there.

I wonder if you care.

A six-pack of Narragansett beer,

Some Camels and the brownie over there.

Every day I stop by like I

Got some place I’ve got to go;

I’m buying things I don’t really need:

I don’t read the Boston Globe.

But I, I think that I

Caught the corner of your eye.

But why, why can’t I try

To say the things I’ve got inside

To you ….

You’re new around here, but in a quiet way.

How long you gonna stay?

Your baby sleeps by the porno rack

And you car’s got Michigan plates.

Winter here’s a lonely time:

snow piles, and generally a pain.

I blew the tranny on my pickup truck,

So I’m driving that rusted-out Fairlane.

But I, I think that I

Caught the corner of your eye.

But why, why can’t I try

To say the things I’ve got inside

To you ….

Pretty soon, she knew my name;

She’d say, “Hey, John-O, how ya been?”

I’d bring her toys that I’d whittled up

To hang over our little baby friend.

I felt myself all changed up somehow,

And I worked like I’d never worked before,

Dropping trees and bucking logs,

All the while thinking of that store.

But I, I think that I

Caught the corner of your eye

But why, why can’t I try

To say the things I’ve got inside

To you ….

But it all ends up kinda’ like you think it might. I got all spiffed up and headed on over to the store. I get there a little later than I usually do. I’d been home whittling up this Canada goose— little thing with wings that flap, so we could hang it over the baby’s crib and she should slap at it—and it would look like it was flying.

Anyways, I get there and Frank is behind the counter reading one of them magazines, all of a sudden I felt myself getting real small, and kinda drifting away. I could hardly even hear him saying, “Yeah, that’s too bad about Carol. She was a real good girl. But I told her not to worry none, that there’s plenty of folks around looking for work, but it would be hard to find one just like herself. Fact is, John-O, she was waiting around here for you to show up; but seeing as how you were so late in coming, and that fellow she was with kinda looked like he wanted to get going, she just wrote down this here note for you. Asked if I’d give it to you here….”

“What’s she say, John-O?”

“Not much, Frank, It just says, …

Dear John-O,

Thanks a lot for everything you did for me this winter. It really meant a lot to me, and I really do wish we could have gotten to known each other better. But life just takes quiet, crazy turns sometimes, and you never know.”

No address. Michigan somewhere, I guess.

So I stuck my head in a Field & Stream magazine so Frank wouldn’t see me. But, like all the folks around here, he knew. It just all seemed kinda weird: Frank, over there, behind the counter saying “Hey, John-O, check out this one over here….”

Damn, damn it I

I had the corner of her eye.

But I…

I didn’t try.

Last of the Boys

Come on over here

and I’ll buy the next round:

cold beer and some shooters

for the boys on the town;

Darby ain’t drinkin’

so let’s live it up

‘cause he’ll drive us all home

in his company truck

Jesus Christ, Jimmy,

man you say that you’re well;

I say we drive into Boston

and stir up some hell;

put a cap on the weekend,

a stitch in the night,

watch the Pats play on Sunday

and the welterweight fight.

That’s all she wrote boys,

there ain’t any more;

that’s why we’re standing here;

that’s what it’s for.

That’s why we all go on working all day

busting our ass for short pay:

~Hey…

Wally there thanks

for the call yesterday;

Yeah, I do need the work

but those people can’t pay;

they’re all pie in the sky

with their heads in the clouds:

the high-talking yahoos

that fill up this town.

Fill up this glass

one more time there old man;

sneak one for yourself

I know that you can.

Nick man come here;

come on tell me it’s true—

you won the college bowl pool

and the trifecta too.

That’s all she wrote boys,

there ain’t any more;

that’s why we’re standing here;

that’s what it’s for.

That’s why we all go on working all day

busting our ass for short pay:

~Hey…

Rogue what you say,

come on tell us the one

about the dog and the bull

and the ministers son;

you told it to Willy,

who told it to me,

who told the whole team

down the alley last week

Well it’s hard to believe

you’ve been married since June.

It seems just yesterday

we’d go piss at the moon—

piss at the moon

and somehow we’d get by

with a pocket of cash

and a piece of the sky.

That’s all she wrote boys,

there ain’t any more;

that’s why we’re standing here;

that’s what it’s for.

That’s why we all go on working all day

busting our ass for short pay:

~Hey…

It seems kind if strange

the quiet of the room;

everyone had to be

leaving so soon.

It seems kind of strange

they got families at home;

I’m the last of the boys;

I’ll have one more alone.

One more rye Howie;

straight up is fine;

I’m okay to drive home,

I’ll just take my time;

keep all the change.

You treated us well;

I’m just trying to figure

if this is heaven or hell.

Heaven or hell

or some pitstop for man,

where we all just pull over

to do what we can.

You do what you can,

and you hope that your right:

I’m the last of the boys

to tie one on tonight.

That’s all she wrote boys,

there ain’t any more;

that’s why we’re standing here;

that’s what it’s for.

That’s why we all go on working all day

busting our ass for short pay:

~Hey…

Many Miles To Go

I see it in your eyes

and in the ways you try to smile;

in the ways you whisper—I don’t know—

and put it all off for a while;

then you keep on keeping on

in the only way you know:

you’re scared of where you’re going

and who’ll catch you down below.

We walked down to the river

to the maples hung from shore

where we talked and laughed

and skipped the stones

that spoke of something more:

five skips for tomorrow,

six skips make a year;

ten skips and forever

there will be nothing left to fear.

And it’s one step and you turn;

two steps and you know

there’s many steps that make a mile

and there’s many miles to go.

There’s many miles before us,

and there’s many a hard won day

and too many lies that tell you why

and keep you from your way.

We dangle over darkness,

over depths we’ll never know:

making faces at reflections

and wondering where to go—

and wonder where the river goes,

and where it all began;

or to just jump in and sink or swim,

for we both know that we can…

And it’s one step and you turn;

two steps and you know

there’s many steps that make a mile

and there’s many miles to go.

There’s many miles before us,

and there’s many a hard won day

and too many lies that tell you why

and keep you from your way.

So don’t fall for your reflection,

for what should be left behind;

a day has never come and gone

without giving back some time:

there’s time for what we know,

and there’s time for moving on;

but this ain’t the time to let slip by,

for it whispers and it’s gone…

And it’s one step and you turn;

two steps and you know

there’s many steps that make a mile

and there’s many miles to go.

There’s many miles before us,

and there’s many a hard won day

and too many lies that tell you why

and keep you from your way.

Trawler

We leave the fog stillness

of a cold harbor town,

and cup our hands

‘round the warm diesel sound—

leave while the children

are calmed in their dreams

by light buoys calling:

“Don’t play around me.”

The kids think their daddy

is so sure where to steer;

they throw in our holds

what they catch from the pier—

they throw in our holds

their after-school days;

what our nets couldn’t drag

will still be okay.

Okay keep your head up

and take care of the home;

I’ll call you next week

on the radiophone.

You say: “Yo, Captain Joe,

on the Marilyn Joe.

Make a beeline back home

on the Marilyn Joe.

Creaking and groaning

play it for me.

We’re the whitecapped and crazy

slaves of the sea—

haul away

heave away

keep what you will;

with a fire in your belly

the holes that you fill.

We leave the bay shallows—

be a waste of our time

to drag empty waves

for a pure lucky find.

We leave the bay shallows

for the edge of the shelf

where the warm waters slide

to a cold deeper self.

There on the edge

we drift nets in the night;

we winch and we pray

and bitch for the light.

We winch and we pray

and bitch for the day—

“Hook on to the rail

and get out of my way!”

“Get out of your bunk’s mates,

and get up from below.

Get into your oilskins—

she’s coming up slow:

We’ll say: ‘yo, Captain Joe,

on the Marilyn Joe.

Bring her into the wind:

Oh, the Marilyn Joe.”

Creaking and groaning

play it for me.

We’re the whitecapped and crazy

slaves of the sea—

haul away

heave away

keep what you will;

with a fire in your belly

the holes that you fill.

We gut all the night,

and pack all the day;

count down to each man

this feast of the waves.

Some take it back

to some love they have found;

some like the wind

they’ll just blow around town.

Six days on the Banks,

our eyes heavy as stones,

we chart a course

that will take us back home.

Docked at the pier,

with our kids by our sides,

we bitch about haddock

the market won’t buy.

We’ll sing: “Yo, Captain Joe,

on the Marilyn Joe:

when will we go

on the Marilyn Joe?

No I don’t mind the rain,

or the wind or the snow—

We’ll set out the trawl

on the Marilyn Joe.”

Creaking and groaning

play it for me.

We’re the whitecapped and crazy

slaves of the sea—

haul away

heave away

keep what you will;

with a fire in your belly

the holes that you fill.

Essex Bay

This house makes funny noises

when the wind begins to blow.

I should have held on and never let you go.

The wind blew loose the drainpipe,

and you can hear the melting snow.

I’ll fix it in the morning when I go.

I’ll fix it in the morning when I go.

I should call you and tell you

how the frost heaves were this year.

You’d laugh and say, “Keeps the riff-raff out of here.”

You’d laugh and say, “In a funny way,

the whole place is kinda queer.”

You know, the State’s finally begun to thin the deer.

Yeah, the State’s finally begun to thin the deer.

And I know the way the tides,

they come and go and flow,

and I know the Essex River

and the clam flats down below.

But there’s something I don’t know

about living all alone

without you …

I sold the lot that looks out,

that looks out past the bay.

Just a pile of sand that’s worth too much to save.

We said we’d beat the greenheads

and build a dreamhouse there someday;

but I got three times the price I had to pay.

Yeah, I got three times the price I had to pay.

And I know the way the tides,And I know the way the tides,

they come and go and flow,

and I know the Essex River

and the clam flats down below.

But there’s something I don’t know

about living all alone

without you …

This house makes funny noises

when the wind begins to blow.

I should have held on and never let you go.

The wind blew loose the drainpipe.

You can hear the melting snow.

I’ll fix it in the morning when I go.

I’ll fix it in the morning;

I love you every morning;

I still miss you every morning when I go …

Jonathan & Elaine

Jonathan McCarney of 37 Brookside Lane

lived for forty years with his wife Elaine;

retired now for twelve years,

he spent his waking hours

wondering if she’d ever be the same—

The same as before

as the pictures by the door.

The same as before,

Christ, I’m asking nothing more.

Then there came the days

when your mind begun to haze,

and you couldn’t remember

the little things no more.

It came on kind of slowly;

the doctors they all told you:

“Not to worry Dear,

it’s just a part of growing old.”

I’d laugh and say: “My sweet dear,

don’t cry and spill your warm tears—

we’re just a pair of old coots all alone.”

Then one day you went down

to the pharmacy in town;

two days later they found you

wandering around.

I put new locks on the door

and swore forever more

I’d never leave you

or let you come to harm.

So for five years I have cared for you—

cradled you and bathed you

and though my eyes are gone

my heart keeps racing on.

I know I cannot blame

but if just once you’d say my name;

My God, I dearly love my poor Elaine.

Then one cold October morning

they came taking you away—

“We’re sorry Mister McCarney,

you can’t care for her this way.”

They took her down the road—

just another aging load.

I swore that I would be with her each day.

Your home is now on Balls Hill,

the state pays your bed bill;

my pension helps to buy you a single room.

I sit down in the chair—

so far away I cannot dare—

Elaine we’ve got to be together soon.

Then Elaine I went home

and I prayed with all my might;

I don’t know if he’ll forgive me,

there’s just so much more wrong than right.

It fit well beneath my coat—

there’s no need for any note.

I’ll turn down the heat

I’ve no use for tonight.

Jonathan McCarney, and his dear wife Sue Elaine,

were waked today at their home on Brookside Lane.

Father Clark prayed on their grave,

Mrs. Blodgett cried and waved—

wondering if they’d ever be the same

Zenmoyang Ni

I lost the time I hardly knew you,

half-assed calling:

“How you doing?

Laughing at my hanging hay field;

I never knew the time

that tomorrow’d bring,

until it brung to me.

Yuan lai jui shuo: “Zenmoyang ni?”

Xianzai chang shuo: “Dou hai keyi”;

Xiexie nimen, dou hen shang ni.

Xiwang wo men dou hen leyi

Dou hen leyi

Dust has blown and snow has covered.

Shorter days been passed by longer.

Poplar trees have dropped their flowers

And spread them on the ground

And then the leaves unfold

Just like I told you so…

Yuan lai jui shuo: “Zenmoyang ni?”

Xianzai chang shuo: “Dou hai keyi”;

Xiexie nimen, dou hen shang ni.

Xiwang wo men dou hen leyi

Dou hen leyi

Love you, damn you, see right through me.

Eyes are scared, a soul is healing.

Paint yourself a wall of feeling

And bring the world around

To the way you are.

It would be a better start.…

Yuan lai jui shuo: “Zenmoyang ni?”

Xianzai chang shuo: “Dou hai keyi”;

Xiexie nimen, dou hen shang ni.

Xiwang wo men dou hen leyi

Dou hen leyi

Knowing time’s no great arranger

It’s getting hard to ‘see you later.

I’ll never meet another stranger

knowing there is something

that we all could know—

you got to let it go…

Yuan lai jui shuo: “Zenmoyang ni?”

Xianzai chang shuo: “Dou hai keyi”;

Xiexie nimen, dou hen shang ni.

Xiwang wo men dou hen leyi

Dou hen leyi

This is my somewhat rough translation:

[Early on I just said, “How are you?

Now I always say, I’m doing awesome.

Thank you, both of you, you are in my heart

I hope we will always have happiness.]

Thoughts…

The folks in this song were a couple named Li Xin and Zhang Hong Nian. They were both artists in Beijing in the early 1980’s where I was attending the Beijing Teachers College. During winter break I tried to visit the parents of a friend of mine. They lived on a commune outside of Shanghai, but, as so often happened back then, my bus was stopped by security forces and I was not allowed to continue, as we were traveling through a “restricted area.” At that time in China, there was only a handful of Americans in the whole country. I didn’t have a lot of money to start with, and most of what I did have I spent on things like cigarettes, whiskey, peanut oil, and fabric to give as gifts. Since the police would not let me go to the commune, I foisted my huge bag of gifts on an old man who had met me in in Shanghai and was to be my guide. The Chinese passengers on the bus (mostly peasants and factory workers) harassed and berated the security men for being rude and petty and for not allowing me to see the all important state secrets: like how many water buffaloes they had in their district.

So, I had to go back to Beijing to a virtually empty campus. The great irony for me is that this rich American was pretty much broke with three weeks to kill (and survive) before school would start again. With no one to hang around with at school and precious little money to spend, I became something akin to a vagabond wanderer meandering the cold streets of Beijng in the winter. I remembered meeting a young a couple named Zhang Hong Nian and Li Xin very briefly earlier in the fall. They had an apartment in a concrete building just north of our campus. I found them, and they took me in with huge open arms. And so I hung out with them and their artist friends for the next couple of weeks.

It was a pretty cool time in my life: I helped Li Xin’s mother—a still fiery follower of Mao Zi Dong— open a hot dog stand; the first one in all of China. She railed against the communists who had lost their spirit. She told me passionate stories about her and her husband and The Long March. She took me to a secret disco she had organized in the warehouse district where a huge crowd was waiting for me (who would much rather be listening to Woody Guthrie) to show them how to dance disco style. I think it was my first experience in performance art. With my new friends, we walked the cold, dusty, and coal smoked streets of Beijing, eating yams cooked over fires in barrels and haggling for scarce chicken and cabbage. I met Chinese poets and writers and thinkers who somehow managed to survive and smile amidst a completely humorless political system. I sat with Zhang Hong Nian for a complete day as he changed a scene in one of his paintings from farmers with sun baked faces to coal miners loading coal into carts (smiling of course). The party officials who had commissioned the painting thought the sun baked faces implied that the farmer’s lives were too hard.

I lived enormously because of their friendship. Li Xin had a wisdom and sincerity that remains unmatched by any other in the thirty years since I spent that time in China. She knew—she simply always knew. It was never that she had an opinion about something. She just spoke directly from her heart— softly, humbly, with a smile if it needed to be tempered, or with an icy directness if it was a truth that had to stand.

I apologize if a native speaker of Chinese hears me singing the chorus of this song. As it was, I had a hard enough time speaking a full sentence much less find a way to make them rhyme. I spent an awesome and inspiring year in China from 1981-82. I went back again in 1989 and spent a good part of the winter in Beijing, but left a couple of months before Tiananmen. Things had changed. I had changed. Li Xin had died from cancer. Zhang Hong Nian moved to New York.

It was eerie for me as I knew that the whole scene in Tiananmen would end badly. I learned from my artist friends eight years earlier about the tenuous balance between freedom and survival. I knew that the same leaders were still in power, and that they would not flinch in the face of a challenge. But political leaders seldom listen to artists. If they did, i t would have ended differently: Li Xin would have found the middle ground and pointed to the truth all around them. Zhong Hong Nian would have painted flowers bursting out of the guns. It might have ended differently.

If any of my old friends from those days find this song let me say: Xiexie nimen; thank you all again.

Searching for an Alibi

Here I am out on the road again.

It feels longer than it was back then;

when I was younger, man, it saw me through—

now it don’t do

what I want it to—

Too ra loo ra loo ra lady I—

I’m just out searching for an alibi

Too ra loo ra loo ra lady I

I’m just out searching for an alibi.

Drinking tea in some dirt village square,

I start to wonder what I’m doing there;

in hard worn skin and gentle peasant eyes

there’s nothing left that I can idolize…

Too ra loo ra loo ra lady I—

I’m just out searching for an alibi

Too ra loo ra loo ra lady I

I’m just out searching for an alibi.

I tease the children and drink with the men,

and we’re all glad that I’ve come back again;

and we all laugh about our crazy lives—

I feel the woman—just to feel alive.

I’ve got no time ‘til the train is gone,

I’ve got no time, but I can’t get on.

I know there’s no way

to check the speed;

but, I know the motion

is all I need…thinking—

Where were you

when you had the chance?

or do you shrug it off as circumstance?

Where were you when you felt inside

some other soul you could realize?

Where were then—

where are you now:

looking back forgetting how?

But look into the eyes of other men—

everywhere the same thing happening…

Too ra loo ra loo ra lady I—

I’m just out searching for an alibi

Too ra loo ra loo ra lady I

I’m just out searching for an alibi.

~Southern China, 1989

Ghetto of Your Eye

I wrote this song back in the winter of 1989 in the dining car of a steam driven train, somewhere along the Trans-Siberian railway, after meeting a group of Russian soldiers fresh from battle in Afghanistan—that poor country that has been a battleground for way too long.

We stare together hours

at the snow whipped Russian plain—

rolling in the ghetto of your eye.

We share a quart of vodka

and some cold meat on the train—

you know too much to even wonder why;

I see it in the ghetto of your eye.

He turns to me and asks

if I’ll play a song about our war.

I know the war,

no need to tell me more—

asking with the ghetto of your eye.

So I play the most of Sam Stone,

in words he cannot understand;

still the tears fall as from a man—

falling from the ghetto of your eye.

I pass to him my guitar:‘Man, I know you’ll play a song;

something where nobody plays along—

no, nobody play along.’

His friends they gather ‘round

and put their arms around

the shoulders of the soldiers of the war,

their cold and crazy mountain war.

His song is barely spoken;

it’s more a whisper in the night:

whistles blow, trains pass each other by—

riding in the ghetto of your eye.

And Pasha, the young soldier,

whose strange and childish smile,

breaks down wailing like a child:

He tears his shirt; the shrapnel is all gone:

“Pasha, boy, the shrapnel it’s all gone—

Pasha boy, the shrapnel is all gone.”

Drunk to hell I leave,

and then I lay awake all night

waiting for the sunrise on the plain—

cold and snow-whipped Russian plain.

Songs of love and brotherhood

blow like rags of empty wind—

blowing through the ghetto of my eye;

building the ghetto of my eye;

staring from the ghetto.

Garden Woman

I woke today and had my tea

and at the window spent the morning:

the same scene I’ve seen so many times

is each day freshly born;

from the ground I turn each spring and fall

come the flowers they are blooming;

you disappear among the weeds—

you are the garden woman.

Long ago you learned to know

the passing of the moons:

to pull the seeds before they’ve sprung

squirreled in bowls around the room.

I laugh to think how many times

I’ve tried to coax a dying flower

to give one more unfolding

to return some precious hour.

I love the hand that weaves the land

from sunshine knits to flowers;

who waters rows of thirsty souls

until they find their hidden power;

but the roots will hold and time will grow

and leave moss upon our stone;

and with every passing season

the mosaic of a home.

When you disappear the sun will bear

how the wind has shaped your beauty;

how in long walks through ancient woods

we stepped both sides of cruelty.

But the tree’s that lean all mean to fall

to give space to free the breathing;

and working through the tangled land

where hope is filled with meaning.

Yeah, I woke today and saw the way

you see the light of morning;

from the ground that pulls us down

there’s a new life freshly born in.

From the ground I turn each spring and fall

let bloom with beauty blooming

the blessed weeds and bowls of seeds:

I love you garden woman.

Metamorphoses

It’s something I‘ve hardly ever thought of:

this simple and rattling old diesel

has always gotten me there and then some;

and so at first I think this sputtering

is just some clog, and easily explained:

some bad fuel maybe, from the new Exxon,

or just shortsightedness on ma intenance.

I’ve always driven in the red before,

and these have all been straight highway miles —

(Except for that short trip out to Zoar Gap

to catch the last of the late season trout,

surprised to find them still rising, sipping

my high hackled Humpy’s and Coachman’s

from dark pools in glazed and shimmered twilight.)

But that was nothing and of no account.

I drove Tuesday down to the town meeting,

and argued about the new town landfill

and proposed cutbacks in school athletics,

and then to Sears for a fifteen amp fuse.

At any rate there is no way around it.

I can only smile sheepishly, glad

that I’m really not in any hurry.

Still I feel like a fool out flagging trucks,

gesturing for help I can’t give myself,

hoping that my lines don’t need to be bled,

and I would have to spend that time thinking

of some way to explain this empty tank

to someone who probably knows better:

You know I always thought that maybe

something like this could happen to me —

but not now, not yet…

Waterfall

You say: “Hey,”

I’ve seen your handprints on the wall;

you’re so damned afraid it’s going to fall;

then you let it go and it didn’t move at all;

and you find life ain’t hard, it’s just a waterfall

You say, “Hey,”

who are you to say that you’re the one

to go telling me just where I’m coming from.

You can have your cake

but don’t frost me ‘til I’m done.

I can’t be fixed and I can’t afford to stall;

because life ain’t hard it’s just a waterfall.

Sometimes it happens we,

we like to play the one-eyed fool,

so we can act like we don’t know what to do—

but it’s a sad-eyed mask

and it’s never really true;

I’ve seen you backstage at the hall,

trembling before the curtain call,

and you know life ain’t hard; it’s just a waterfall.

And you feel it how

it’s coming at you now;

and you feel it how

it’s all around you now—

and you’re loving and you’re feeling

maybe mixed up,

maybe stealing

a little time

I’m just amazed

that somehow we keep dealing…

You and me we spin, we drift,

we’re daring to be free:

in a mirrored calm time echoes

like a sneeze—

and just when you think it’s all a dream:

and everything you are has already been—

just when you think you’ve seen it all

a boiling wind comes screaming in a squall

and you say life ain’t hard,

it’s just a waterfall—

yeah, life ain’t hard; it’s just a waterfall—

life ain’t hard; it’s just a waterfall.