Transitions

To Create Effective Transitions in Essay Writing

The Power of a Natural and Logical Flow

The crazy thing about transitions is that we are already masters of transitions. All of us have been practicing and perfecting a natural and logical flow for as long as we have been speaking. So whats the big deal when trying to employ effective transitions in our writing?

In all of my years of teaching and writing, no one has really defined what a paragraph is that has left me feeling like “Whoa, now I know!” When I write, I create new paragraph whenever it “feels” like a paragraph is needed. Where and how that “feeling” happens is the fodder for debate.

For the most part, my shifts are pretty much in line with accepted paragraph usage. I transition to a new paragraph when my thoughts shift in a new direction or there is a change—often even a very slight change—in mood and tone. Sometimes, I’ll even just hang a sentence out in space to give the reader a break or a pause for thought, but never as a break or pause for the writer, which would be like stopping in the middle of a conversation just because you want to rest.

As humans we have a great intuitive sense for how to complete a thought, how to move to a new thought, and how to end a conversation with some degree of grade and normality. A good writer develops the confidence to trust that intuition; a bad teacher hyper-analyzes it.

The annoying thing is that most of us have been taught (usually by that hyper analyzing teacher) that transitions are some kind of visible and mechanical bridge, and without the bricks and mortar of that bridge an essay will fall to pieces and crumble into a disarray of babbled words and incoherency.

Not true! An essay falls apart when the unifying theme of the essay becomes unglued or weighted down by too much extraneous stuff—stuff that does nothing to further your essay, stuff that makes a reader say, “I have no idea what you are trying to say!”

Simply put: know your topic and stick to it. Everything else will fall into place.

There is an Irish story of twin brothers, one who was very studious and the other not studious at all. Their assignment in English was to write an essay about a pet. After the papers were graded, the teacher called the less studious brother aside and said in a chiding way: “ Your essay about your pet dog was exactly the same as your brother’s essay.” To which the he responded, “What did you expect? It’s the same damn dog.”

The point of that story? If the reader knows what you are writing about, and you stay more or less focused on that topic (or topics) your reader will not be confused by how you structure your paragraphs or craft your transitions between paragraphs. If it reads like a conversation from your head and heart, no lasting damage has been done to the fabric of the universe.

But it still might be a lousy essay. And maybe it is lousy because of the way you transitioned (or more than likely did not transition) between paragraphs. Maybe your essay resembles more of a trip down a mountain ski slope in an old VW Beetle with your little brother punching you in the arm and yelling “Punch Buggy” the whole way down the hill.

The bottom line is that an essay needs—as in really needs—a natural and confident flow. A reader needs to feel that the writer is in control from start to finish, and anything that interrupts that flow is more annoying than it is engaging; otherwise, your essay is doomed to that anonymous dropbox in the cloud where most essays go when they die.

So make your essay live. Don’t just write—breathe! Make your essays as alive as you are. Be real and write about what you know, and if you don’t know, don’t fake it—learn what you need to know, and then start writing. And opposed to what many teachers teach, use the voice that is most alive in your head—even if it is the dreaded “I” voice. It is, after all, you who are writing. Be real. Avoid words you don’t already know and use. You don’t want to be one of those “phoneys” that Holden Caulfield singles out in Catcher in the Rye. Be real because you really are real and no one is better than you at being you.

So easy for a wordy English teacher to preach, and I am not the one writing the essay (Oh my god, he used the I voice in an essay!) and you are not the one who assigned the writing prompt, but like Odysseus sailing into the Straits of Skylla, the only way out is through, so write you must.

My long-winded preamble is over, and now I will give you a few tricks to help you create transitions in a traditional five-paragraph essay or any kind of formal essay that might be graded in a traditional and rigorous way by the mighty red pen of academia.

Technique #1:

Connecting Thoughts

SOYET ANDOR NORFORBUT

My little acronym is meant to sound like a Russian spaceship, but it is merely a disguise for the all of the hidden coordinating conjunctions—those cool little words that connect independent clauses to create longer compound sentences, and which tie together two or more “related” thoughts.

That’s the main point: “two or more related thoughts.”

Now here is my little trick: “If” you could (thought you won’t actually do it) add a conjunction to the end of one paragraph and lead into the opening line of the next paragraph you have created a logical transition—a bridge between paragraphs that a reader can cross to your new thought without falling into the roiling water of confusion.

For Example:

Huck Finn escapes society by escaping from his abusive father, but Jim seeks freedom from slavery for himself and his family.

The transition sentence at the end of the paragraph is:

Huck Finn escapes society by escaping from his abusive father.

The topic sentence or narrow theme of the next paragraph is:

Jim seeks freedom from slavery for himself and his family.

Technique #2:

Stealing and Thievery

Technique number two uses the coordinating conjunction trick and takes it one step further.

Steal a theme, a topic, an idea—or even just a word—from one body paragraph and use it to start your next paragraph.

For Example:

The cunning deceits of Odysseus help him overcome the trials he faces while trapped in the Cyclop’s cave, [but] without bravery, Odysseus could never pull off his cunning plans.

The transition sentence at the end of the paragraph is:

The cunning deceits of Odysseus help him overcome the trials he faces while trapped in the Cyclop’s cave.

The topic sentence or narrow theme of the next paragraph is:

Without bravery, Odysseus could never pull off his cunning plans.

Technique #3:

The Conjunctive Adverb Trick

Like a coordinating conjunction, conjunctive adverbs connect two or more related independent clauses—but even better, conjunctive adverbs show the relationship between those independent clauses.

Conjunctive adverbs are words and/or phrases like:

accordingly, furthermore, moreover, similarly,

also, hence, namely, still,

anyway, however, nevertheless, then,

besides, incidentally, next, thereafter,

certainly, indeed, nonetheless, therefore,

consequently, instead, now, thus,

finally, likewise, otherwise, undoubtedly,

further, meanwhile, in spite of, on the other hand,

in contrast, on the contrary, ETC…

In the same way as techniques one and two, “if” you could put a conjunctive adverb at the end of a body paragraph and lead into the first sentence of the next paragraph, you have an effective transition—as long as you are using the conjunctive adverb correctly.

For Example:

In Walden, Thoreau urges us to live more simply and thoughtfully; moreover, Thoreau gives an example of his own life and his own idea of simplicity and thoughtfulness through his experiment on Walden Pond.

The transition sentence at the end of one body paragraph is:

In “Walden,” Thoreau urges us to live more simply and thoughtfully.

The opening sentence of the next paragraph is:

Thoreau gives an example of his own life and his own idea of simplicity and thoughtfulness through his experiment on Walden Pond.

Technique #4:

The Dangling Paragraph

This technique can save an essay from itself. Oftentimes, we have a paragraph or thought that is hard to connect to the next paragraph. The dangling paragraph comes to the rescue.

A dangling paragraph is a paragraph that is very brief compared to the body paragraphs it is sandwiched between. It’s effect on the reader is meant to be clear, concise and compelling—and even startling. It can be a statement, a question, or just a philosophical pondering.

For Example:

Because I can imagine myself sailing in a twilight breeze across Pleasant Bay, I will put up with these days of gluing, screwing and painting, varnishing and rigging my old sailboat. Sometimes I wish I had the money to just buy a boat that doesn’t need so much of my time, but like anything else in life that steals my time, I must figure it’s worth it—and it is. I do other things with my time where I don’t have the same clarity of purpose. It is a rare moment of quiet in my house; the kids are all off with Denise somewhere, and though the grass is absurdly high; the van desperately needs an oil change, and the gutter is hanging by a twisted coat hanger, I sit here and force a few words out of emptiness. A part of me wants to show the folks in my writing communities that I practice what I endlessly preach to them—face the empty page! But it’s not that simple; I’ve been doing the same thing for almost thirty years, seldom with any goal but the action of writing itself.

Is it worth it? [This is the dangling paragraph!]

Everything that I write returns to me obliquely. I’ve never written for a publication; I’ve never even tried to get anything published, save for a small book of poetry and a couple of CD’s. I’m a whiz when it comes to writing recommendations, and I can write a decent song or poem for any occasion, but I still can’t say that I write out of a labor of love or because I have some over-arching goal. I write because it gives purpose and meaning and clarity to my life. It stills me when I need to be still, and it roils me out of my ignorant slumber when I need to wake and see the light of day. Used wisely, writing humbles my arrogance and helps me open my arms and doors when I might otherwise retreat into a self satisfied shell of complacency. It is worth a long day on the water to be there when the wind and tide help beat the way to a new harbor.

My goal with my short dangling paragraph was to shift my topic and to get my readers to ask the question with me. It’s purpose is to get the reader to stop, read, rethink and shift gears—as in to redirect the topic of the next paragraph. It allows a writer to avoid an otherwise messy transition and move his or her essay in a new direction.

Make sense to you?

That last paragraph is an example of another dangling paragraph! Used with care and discretion, it is an effective technique.

Used as a habit, it will soon become a bad habit.

Openings & Closings…

Both 8th grade and 9th grade are working on opening paragraphs, and I bet more than a few of you are a bit stumped on how to start. Some of you may even be working on a conclusion.

Wouldn’t that be nice.

My best advice is to use the latest version of my iBook “Fitz’s Literary Analysis Rubric.” The latest version is in the Materials section of your course on iTunes U. If you do not have the latest version, simply delete your version in iBooks and upload the new version.

You can also go to the Opening Paragraphs site on my Resources and Rubrics Page, which has essentially the same information as in my iBook.

Here is a good opening paragraph for The Odyssey already turned in by Ahbinav Tadikonda. It might give you an idea of what might work for you–in your own words and ideas!

Everyday is the same: Odysseus travels the vast seas with his crew in hope to return home only to be disappointed day after day. Enduring the pain of a thousand men Odysseus keeps moving on, being the hero he is. But what is a hero anyways? When most people think of a hero, they think of a tall, muscular, and handsome being that could do no wrong; however, Odysseus is not all that perfect. Odysseus, is often rude, disrespectful, and not always the most attractive male. However he is still a hero. He shows he is a hero by the way he handles difficult times. For Odysseus disaster as constant as the sun rising everyday. Even getting out of bed has become dangerous for him. From battling cyclops’s to being away from family for over 17 years, it really makes you ask: how is it that through all the terrible times Odysseus still shows his maturity, bravery and courage?

For you ninth graders, check out this opening written by Mike Demsher a couple of years ago:

Throughout human history, we have advanced. Whether it is electronically, medically or socially, we have moved forward to a better society; however, could we be moving in the wrong direction? We have advanced our lives to a point where we are constantly hurrying with everything we do. We have been moving into a world where there is no real thought. We are in a philosophical dark age. The only way to snap ourselves out of it is to slow down and think. We must live deliberately each day and remember who we are meant to be. In Henry David Thoreau’s Walden, Thoreau urges us to live our lives purposefully and to not give up who we are. He wants us to live with our eyes open and not to fall into the blur that society is moving towards. Henry David Thoreau wants us to live deliberately.

Done with all that…?

If you are working on your conclusion, go to my “Essay Conclusions” website and see the rubric there, which is geared towards concluding a literary anlaysis essay.

Please steal my rubric from me!

For the ninth graders writing an essay on Walden, the example essay on my “How to Write Literary Essays” site uses a Walden essay ( and a fine one) as an example of how to put together an entire essay.

It’s a big project, and I am really only hoping that your write carefully and use the rubrics carefully. If you do, you will do well.

I hope this helps!

Hope To Write a Literary Analysis Paragraph

To help you prepare to write our “Thoreau Essay,” please read through the iBook I uploaded to iTunes U. You can also visit my web page on how to write a literary analysis paragraph.

We will “start”our first paragraph tomorrow in class, though you are free to get started tonight if you wish.

The first paragraph is due on Monday.

Finishing Walden…sort of…

We are not finishing Walden, but we are finishing a good chunk of some of Thoreau’s influential passages and philosophical statements.

Before class on Thursday, upload the full abbrieviated Walden 1-4 and read the “rest” of the book slowly and deliberately. Highlight what you feel is the most important sentence or section from each paragraph. Restate (riff) it in your own words. You must be able to show me your work. If you reach an hour’s time working on this, you may stop and finish it for Friday.

We will discuss these paragraphs in class and try to discover the most basic “things” that Thoreau is trying to get at.

We will use these “things” to begin an essay that explicates several themes from the parts of Walden we have read–“or” you can focus on a single theme developed in one of the four chapters.

Getting Things Done…

You guys are a great class. I mean that sincerely. What you do need to work on is getting your work turned in when and how I want it turned in.

By this point you should have turned in the Literary Reflections for the class periods so far this week. We can work on the next one in your next class. It is frustrating when the work is not there to be graded “when” I am doing the grading. It is frustrating when you do not comment on my blog posts as I have no idea whether you read them or not and if you have any questions.

The semester is winding down and these reflections are your final grades–an easy sixteen points in my book.

All you need to do is to write sincerely using “paragraphs;” use quotes to back up your thoughts, and spend a bit of time editing and proofreading and you turn in a pdf which looks good and reads fluidly and naturally–like your voice when you speak with me. Post it to your blog and make sure it looks just as good!

If you put in the time and effort now, you will be amply rewarded when we begin our next major essay after break.

Did you read this and get it. For your comment all you need to do is write a number between 50 and 100. Nothing else.

If you don’t, you have “failed” this test!

And you will be sad…

(These 250 words or so took me five minutes to write)

Paragraphs…

From what I have read so far, I have really loved the reflections. Hopefully, you have posted these to your blog, so every can see and read the diverse—but focused—way each of you has approached the assignment. There is one thing that many of you need to do—

Paragraph!!!

A big part of this reflection writing is for you to practice paragraph writing, to learn when you are shifting to a new thought and/or direction, and to do the proofreading and editing needed to make your reflection publishable: meaning, fit for people to read.

The document you turn in to iTunes U should also look good and be publishable.

I want you to write the reflections in class. Leave fifteen minutes for editing and publishing. This will give me a good idea of what a good production rate is for each of you.

As it is, I am asking you to write a bit less than fifteen words a minute. Not a lot, but not a little either. There is not a lot of room for screwing around.

So get to work…

In my Rocky story, Rocky is amply a metaphor for you guys writing without a rubric.

Some Thoughts about Your Haiku…

I have had a go0d read so far reading your haiku. I have a couple of thoughts…

I never quite know how to teach how to use specific imagery. When I say “specific” maybe I mean “real.” because every reader–wants to “see” what you are seeing in a real way.

- avoid anything generic that might mean something totally different depending on who and where you are. The ocean is different all of the world. There are a million types of flowers, so give your flower the name: rose, tulip, dandelion. What is in the field? What bug is it? The art of the haiku is in creating an image and then creating a mood, a meaning, or an insight.

- Emotions are tricky to write: joy and sadness, pain, sorrow don’t mean much on their own. Use specific imagery to create the sense of joy, sadness–or whatever emotion you are trying to capture in your haiku.

- Get rid of ALL unneeded words!

Here is Basho trying to capture “persistence”

Autumn moonlight–

a worm digs silently

into the chestnut.

Here is Issa capturing beauty:

Blooming Garden

Moonlit Wind Blowing

Silver Fragrance

Here is Buson capturing the essence of manual labor:

Blow of an ax,

pine scent,

the winter woods.

My haiku techniques should really be accompanied by you searching out the haiku of the Japanese masters. Check out this site and see what mean!

Literary Analysis Paragraph Mistakes

The devil is always in the smaller details, and it is these details that jump off the page when a reader is reading, a teacher is grading, or your boss is wondering why the heck he or she hired you in the first place.

I should not have to give you a checklist as all of these details are explained in the literary analysis paragraph rubric. It is as easy to make these mistakes as it is to avoid them.

First Look

Formatting

The most glaring errors—and the errors I catch most easily—are simple formatting errors and omissions of detail. Here is a list of the most common mistakes in formatting a literary analysis paragraph.

- The document has the wrong file name.

- Assignment information is missing or incomplete

- The title is not centered

- The quote is not centered, not in italics, or you do not cite the source of the quote.

- You do not tab in your first sentence.

- Book titles not capitalized or italicized.

Opening Paragraph

GUIDING THEME

This comprises the first third of your paragraph and guides the reader in the direction your paragraph. The three parts act together to clearly state the reason your paragraph exists.

- Broad Theme: The most common mistake is to make this a long and complicated sentence. The only purpose of the broad theme is to “engage” the readers interest by introducing an enduring theme and tying it into your narrow theme.

- Narrow Theme: The most common mistake is to omit the one word theme and a specific reference to the literary piece in the sentence. This sentence shows how the broad theme is used in the literary piece.

- One/Two Punch: Don’t go back to your broad theme here; this is the place to narrow down your narrow theme even further to a specific character, event or observation—and be sure to reference your theme word or phrase again.

Body Paragraphs

TEXT REFERENCE & SUPPORT

This should fill up the center third of your paragraph. It is the physical proof of your theme working within the text of your literary piece.

- Setup: Oftentimes a writer does not provide enough specific detail for the reader to fully understand the context of the coming quote (the smoking gun). Be sure to fully create the “image” a reader needs to “see” by including a meaty and specific who, what, when, where, why leading into the actual text support,

- Smoking Gun: This can only be the actual text from the literary piece. The most common mistake is to forget to cite the source of the quote, or to forget to italicize the quote–or to forget to block quote the selection if it is longer than two lines on the page.

EXPLICATION & EXPLANATION

Head and Heart: This is the foundation of your paragraph. Without it, your paragraph will be as empty as it is shallow. It shows and tells the reader how your theme is relevant to your text reference. It makes reading your paragraph a worthwhile (edifying) experience.

- Head and Heart: By far the most common mistake here is to write about the theme itself instead of how the theme is specifically used in the piece of literature you are analyzing–and even more specifically how the theme is used in your text reference.

- The first sentence of the head and heart should explicate the quote.

- Never write anything along the lines of “This quote shows…” Or “What this quote means is…” Quotes don’t mean anything! The way the plot unfolds means everything, so refer to the action in the piece of literature.

- Do not tab the first sentence of the head and heart because it is not a new paragraph.

- Check this section and make sure that “every” sentence refers back to the literary piece (and your narrow theme) in some way shape or form.

Finishing Clean

TRANSITION OR CONCLUSION

This part of your paragraph should signal your readers that they have either reached their destination or you are talking the next exit off the highway. There is no reason to be wordy here. Too many words is like trying to clear a muddy puddle with your hand.

The most common mistake here is referencing your broad theme without referencing the piece of literature you just finished analyzing.

- Get On: The biggest mistake when transitioning to a new paragraph is when there is no logical flow between paragraphs.

- My rule of thumb is that I “should” be able to put a conjunctive adverb (moreover, finally, however, etc) or a conjunction (so, yet, and,or, nor, for, but) between the last line of one paragraph and the first line of the next. If you can’t do that, there might be something more you need to do….

- Get Out: It is critical to end a final or single paragraph with a sense of finality, so my advice is to finish it clean.

- The most common mistake here is to introduce a new thought that you haven’t already discussed in your paragraph–or you forget to refer back to your one-word theme AND the literary piece.

- Never refer back only to the broad theme. This final sentence needs to capture your narrow theme PLUS the added insight of your explanation and explication about the piece of literature you are analyzing.

Final Thoughts

I am not so vain as to think that my rubrics are the end all/ be all of how you should write or present a writing piece, but it is massively important that you learn to answer a writing prompt or assignment with meticulous attention to the details that are important to your “boss” (whatever shape that boss takes). If you are working in a supposed “collaborative” group and your partners are not exactly collaborating, you need to take control of the final product before it is presented to “the boss.”

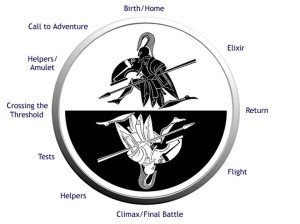

The Heroic Cycle

The hero cycle is not a rubric created for storytellers; it is the primal urge of all people—across ALL cultures—to experience within their own lives the transformation of being a hero. Every ancient culture that has had its history recorded has some epic poem or story to guide its people. The heroic cycle represents the power of hope over despair; it gives us all the chance for redemption—even in the hardest of times. It is a recognition that without agnos (pain) there is no aristos (glory), and, in that sense, it validates even the most common and hard-bitten of lives by making the lives of every man, woman and child that has ever lived uncommon, unique, and worthwhile.

The hero cycle is not a rubric created for storytellers; it is the primal urge of all people—across ALL cultures—to experience within their own lives the transformation of being a hero. Every ancient culture that has had its history recorded has some epic poem or story to guide its people. The heroic cycle represents the power of hope over despair; it gives us all the chance for redemption—even in the hardest of times. It is a recognition that without agnos (pain) there is no aristos (glory), and, in that sense, it validates even the most common and hard-bitten of lives by making the lives of every man, woman and child that has ever lived uncommon, unique, and worthwhile.

It is not an absurd idea to recognize the greatness and possibilities of our own lives. It is not absurd to think we have an epic tale worth telling, and it is certainly not absurd to examine every experience through a reflective lens and to start to appreciate the implications of transformation which heroic poetry represents. As human beings, we are hard-wired to need this epic poetry. We can’t just read the epic as a story and move on. We have to know the story and build and incorporate the allegory into our own lives; otherwise, we will run from the battles of life; we will avoid the straits of Skylla and the lair of the Cyclops; we will shun the Gods who come disguised to us and coddle the children given to us; we won’t shed tears for common friends, and we will lock out every stranger and blame our mishaps and misdeeds on the gods.

In short, we will not be remembered, and no songs will be sung about us. The saddest part is that you may think this is all exaggeration and hyperbole. But, it is not! Our lives are full of stories that use and embody the heroic cycle. In fact, I have a hard time trying to think of any “great” movie, book, or story that in same way, shape or fashion

Try to come up with a book or movie that you feel is a meaningful and powerful story that follows this heroic cycle. Fill in the blank boxes with a brief description of the scenes that best illustrate the use of the hero cycle in the story.

The assignment will be posted on iTunes U. If you have any problems, you can use this rubric. Open it in Pages.

Download the rubric:

Freshman: A Trip To the River

It seems like somethings is always obscuring view. My eyes try to wrap around the gnarled trunks of swamp maple lining this river. My poor students are somewhere between lost, aggravated and confused. What is the river to them? Perhaps it is just a string of water: cool because it is fall, or maybe just cool because I we are not in class. Or are we. I usually feel a bit boxed in in the classroom, while outside my mind does not wander, it embraces what is impossible to embrace: these woods, waters, bogs and trails that crisscross this, my childhood home. I wonder what great disservice I would do to my students if I simply opened the door of the classroom and pointed them toward this river and said, “Go, explore, think, write and learn what those woods have to teach. Come back to me in June and tell me of your time!” Nature makes me make promises I seldom keep. I don’t come back as often enough as I say I will. And that ain’t right.

It seems like somethings is always obscuring view. My eyes try to wrap around the gnarled trunks of swamp maple lining this river. My poor students are somewhere between lost, aggravated and confused. What is the river to them? Perhaps it is just a string of water: cool because it is fall, or maybe just cool because I we are not in class. Or are we. I usually feel a bit boxed in in the classroom, while outside my mind does not wander, it embraces what is impossible to embrace: these woods, waters, bogs and trails that crisscross this, my childhood home. I wonder what great disservice I would do to my students if I simply opened the door of the classroom and pointed them toward this river and said, “Go, explore, think, write and learn what those woods have to teach. Come back to me in June and tell me of your time!” Nature makes me make promises I seldom keep. I don’t come back as often enough as I say I will. And that ain’t right.

Later… It was great fun making our way down to the river. Really, so much of my childhood was spent cavorting up and down the river with friends and often alone and old canoes and rowboats. It is something we should continue doing throughout the year. I hope that you got something out of our trip today that is just a little bit different than you would get in the normal class day. I know we only spent a short time sitting by the river, stepping over gnarled roots, and lifting our feet high enough to avoid the poison ivy, but we’ll know that in a day or two:) I hope you were able to get a few thoughts down yourself that you can expand upon tonight or tomorrow and craft into a journal entry that you can savor years from now. Most of my old journals are lost, and it is one of the true sole regrets of my life. Memories are great, but the ravages of decades of time take its toll on true remembrance. And this is what I am trying to give you: the chance, the opportunity, and the time to create your own remembrances of a blessed time in your lives. What you make of this opportunity is up to you. A good writer writes “fully,” meaning, he or she crafts words that are recreated in the mind with the imagery rich and exacting, with nuanced thoughts articulated

And this is what I am trying to give you: the chance, the opportunity, and the time to create your own remembrances of a blessed time in your lives. What you make of this opportunity is up to you. A good writer writes “fully,” meaning, he or she crafts words that are recreated in the mind with the imagery rich and exacting, with nuanced thoughts articulated with clarity and energy, and with actions and sounds pulsing with the original force. This is not something that just happens. It is painstaking work sometimes; other times the words flow as if from a flooded spring. But it is always worth it. Try to get your two journal entries posted to your blog before class on Thursday. I am eager to read them and share in your evolution as a writer and thinker. If you have pictures, post them too! I always had a pad of paper and a pen and rather horrible sketching skills. Do you remember what the sassafras leaf looked like? The Virginia Creeper? Can you remember the white pine from the red pine? The oak from the maple? And what of the burrs and scratches you were probably covered in? All time is

Do you remember what the sassafras leaf looked like? The Virginia Creeper? Can you remember the white pine from the red pine? The oak from the maple? And what of the burrs and scratches you were probably covered in? All time is

All time is important time. Remember time in words, not hours.

Remember time in words, not hours.

Fitz-Style Journal Entry

Upload the Fitz Style Journal Entry Rubric

How To Create a Fitz Style Journal Entry

Set the Scene & State the Theme; Say what you mean, and finsih it clean

When writing a blog post, is important to remember that a reader is also a viewer. He or she will first “see” what is on the screen, and that first impression will either attract their attention and interest—or it may work to lose their attention and interest; hence, a bit of “your attention” to the details will go a long way towards building and maintaining an audience for your work. Plus, it gives your blog a more refined and professional look and feel—and right now, even as a young teenager, you are no less a writer than any author out there.

So act like a writer. Give a damn about how you create and share your work and people will give a damn about what you create! It is a pretty simple formula.

The “Fitz Style” journal entry is one way to do it well! I call it “Fitz Style” only because I realized that over time my journal posts began to take on a “form” that works for me. Try it and see if it works for you. You can certainly go above and beyond what this does and add video or a podcast to go along with it—and certainly more images if it is what your post needs. Ultimately, your blog is your portfolio that should reflect the best of who you are and what interests you at this point in your life presented in a way that is compelling, interesting, and worth sharing.

One of the hardest parts of writing is finding a way to make sense of what you want to say, explain, or convey to your readers–especially when facing an empty page with a half an hour to kill and an entry to write (or a timed essay or exam writing prompt). The Fitz Style Entry is a quick formula that might help you when you need to create a writing piece “on the fly.” At the very least, it should guide you as your write in your blog, and at the really very least, it will reinforce that any essay needs to be at least three paragraphs long! I’ve always told my students (who are probably tired of hearing me recite the same things over and over again): “If you know the rules, you can break them.” But you’d better be a pretty solid writer before you start creating your own rules. The bottom line is that nobody really cares about what you write; they care about how your writing affects and transforms them intellectually and emotionally as individuals.

If a reader does not sense early on that your writing piece is worth reading, they won’t read it, unless they have to (like your teachers), or they are willing to (because they are your friend). Do them all a favor and follow these guidelines and everyone will be happy and rewarded. Really!

Formatting

How something “looks” is important. Never publish something without “looking” to see the finished product in your portfolio or blog.

Interesting Title

After the initial look, the title is the first thing a reader will see. The title should capture the general theme of your journal entry in an interesting and compelling way.

Interesting Title

After the initial look, the title is the first thing a reader will see. The title should capture the general theme of your journal entry in an interesting and compelling way.

Eye-catching Image

An image embedded in your post is the final touch of the formatting. A picture really does paint a thousand words and this final touch prepares your readers and entices them to read the important stuff—the actual writing piece you create.

Opening Paragraph

The “Hook!”

A hook is just what it says it is—a way to hook your reader’s attention and make him or her eagerly anticipate the next sentence, and really, that is the only true hallmark of a great writer!

Set the Scene

Use your first paragraph to lead up to your theme. If the lead in to your essay is dull and uninspired, you will lose your readers before they get to the theme. If you simply state your theme right off the bat, you will only attract the readers who are “already” interested in your topic. Your theme is the main point, idea, thought, or experience you want your writing piece to convey to your audience. (Often it is called a “Thesis Statement.)

State the Theme

I suggest making your theme be the last sentence of your opening paragraph because it makes sense to put it there, and so it will guide your reader in a clear and, hopefully, compelling way. In fact, constantly remind yourself to make your theme be clear, concise and memorable. Consciously or unconsciously, your readers constantly refer back to your theme as mnemonic guide for “why” you are writing your essay in the first place! Every writing piece is a journey of discovery, but do everything you possibly can to make the journey worthwhile from the start.

Body Paragraphs

Say What You Mean

Write about your theme. Use as many paragraphs as you “need.” A paragraph should be as short as it can be and as long as it has to be. Make the first sentence(s) “be” what the whole paragraph is going to be about.

Try and make those sentences be clear, concise and memorable (just like your theme) and make sure everything relates closely to the theme you so clearly expressed in your first paragraph. If your paragraph does not relate to your theme, it would be like opening up the directions for a fire extinguisher and finding directions for baking chocolate chip cookies instead!

And finally, do your best to balance the size of your body paragraphs. If they are out of proportion to each other, then an astute reader will make the assumption that some of your points are way better than your other points, and so the seed of cynicism will be sown before your reader even begins the journey

Conclusion

Finish It Clean

Conclusions should be as simple and refreshing as possible. In conversations only boring or self important people drag out the end of a conversation.

When you are finished saying what you wanted to say, exit confidently and cleanly. DON”T add any new information into the last paragraph; DON’T retell what you’ve already told, and DON’T preen before the mirror of your brilliance. Just “get out of Dodge” in an interesting and thoughtful (and quick) way.

Use three sentences or less. It shows your audience that you appreciate their intelligence and literacy by not repeating what you have already presented!

Now give it a try!!!

Recent Comments