No Results Found

The page you requested could not be found. Try refining your search, or use the navigation above to locate the post.

From the deck of my sister’s house on the Oregon coast, I can see the breakers lumbering in as the heavy morning fog slowly burns away. In true west coast style, I brewed a coffee that is strong and pungent and will guide me through my own morning fog. I was reading until late last night in David McCullough’s book, John Adams. John Adams is an interesting character with whom I feel a marked affinity at every turn in the book (a book which has way too many turns!). Maybe it is my distance right now from New England that creates the affinity. I am certainly not a very political person, but I relate to Adam’s need for, and dedication to, his family, his love of walking the countryside, and his practical working of the earth closest to him—an earth replete with stone walls, fields, orchards, rivers, wood-splitting, and escapes to the sea—but most importantly, his escape to “quill and paper” to better expose his vanities and commonality, and to find a pathway to express the depths of his speculative thinking.

Though he often lived low, he always aimed high, and that is the demon and angel I wrestle with every day. With summer almost over, there is as much undone as done. I feel like a waterbug that has skittered across a great expanse of time and water without breaking below the surface to exploit the riches below. There is no new batch of songs, no folio of poetry, and precious few chapters in Hallows Lake, my own—and only—labored attempt at fiction. I can console myself with ten or twelve decent essays and narratives written in support of the writing communities I oversee during the summer months, but not much creative work, which, ironically, is the strongest suit in my deck of writing cards.

Writing is still the time that is stolen from the day and not the purpose of the day itself. My own purposes and instinctual priorities, like Adam’s, are the myriad responsibilities of the lifestyle I lead, but Adams took his life further, wider, and deeper. As a public figure, Adams was prodded and coerced by the dictates of a needy public and the enormity of the political upheavals of his time, while I am only inspired by a vague sense of my potential and a mysterious need to put words to the narrow confines of my own experiences and my own sense of the world closest to me.

At this juncture in my life, I wonder if that is enough? I wonder if I need to put myself on a larger stage and summon the courage to place my life in front of a larger audience and let the chips fall where they may? A week from today I will be back in the classroom in front of sixty 14 year-old boys who I need to inspire to somehow give a damn about everything I ask them to do. My monologues need to be reinforced by a model of hope and action. Too often it is true that we teach what we do not do ourselves; too often we only build a scale model of our true greatness out of brittle plastic and weak glue that can only weaken over time, and too often we don’t answer the clarion of our own callings, and so we sit, smugly satisfied with the diluted reality of our lives.

What we think is only made real through what we say and do. The waves rolling onto the shore in front of me now are barely perceptible to the boats fishing out of Nehalem Bay. The power of the water is only evident where the water breaks and crashes onto the beach. No one is here in Manzanita content to simply look beyond the horizon. We are here because the sea meets the land in a continual expectation of beauty and awe-inspiring power. We walk the beaches in search of both the detritus and bounty of the sea. If that sea gave us nothing; if we weren’t convinced there was not more to be had here than from the confines of our own yards, we would just have stayed at home and gathered the glory of our own gardens.

I have to set to sea and trawl the infinite stew of what I carry within me, and I have to take myself to where those words curl onto a more public shore. I need to take my garden to the sea and spread my wares upon the waves and let the beachcombers gather what they wish to keep.

It is not the history of John Adams I am after.

It is his unflinching and steady spirit.

I have been teaching, writing, playing and performing for over thirty-five years, while during these last ten years I have been given the time and space and support (and funds) to create a classroom and pedagogy that through stops and starts and a deliberate evolution of ideas and practices has come to be known simply as “Fitz English.” I have always been somewhat of a traditionalist in my approach to what I teach, but I have always been driven to improve the classroom experience in a way that empowers students to become more confident, fluent, and engaged readers and writers; moreover, I have never “clung to my ways” or to any “ways” for that matter! When something worked, I tried to make it better. When something did not work, it went into my overflowing bin of teacher trash–and a mighty big bin it is. I can only thank my students and an enlightened and indulgent administration for placing a sacred trust in my hands–for the learning and practice of effective and powerful writing and reading skills is a sacred trust, and a duty that any wise teacher lives through in every class he or she teaches.

I have been teaching, writing, playing and performing for over thirty-five years, while during these last ten years I have been given the time and space and support (and funds) to create a classroom and pedagogy that through stops and starts and a deliberate evolution of ideas and practices has come to be known simply as “Fitz English.” I have always been somewhat of a traditionalist in my approach to what I teach, but I have always been driven to improve the classroom experience in a way that empowers students to become more confident, fluent, and engaged readers and writers; moreover, I have never “clung to my ways” or to any “ways” for that matter! When something worked, I tried to make it better. When something did not work, it went into my overflowing bin of teacher trash–and a mighty big bin it is. I can only thank my students and an enlightened and indulgent administration for placing a sacred trust in my hands–for the learning and practice of effective and powerful writing and reading skills is a sacred trust, and a duty that any wise teacher lives through in every class he or she teaches.

The seven guiding principles of The Crafted Word are the product of my own education in the hardscrabble reality of the classroom. The seven pillars: Read, Write, Create, Share, Collaborate, Assess, and Reflect capture the essence of what it takes to enable a more profound and enriching experience of a sustainable and dynamic literary life. I try to give my students whatever they need to flourish in their next academic year; however, I try even harder to build a foundation and approach to reading, writing and content creation that will serve and guide them throughout the odyssey of each of their respective lives.

For a new person entering my classroom, the most noticeable feature of my classroom is what is missing–desks! There are no desks. There is, however, a large round table around which students can stand or sit on stools (not chairs). It is at this table where we meet to discuss the coming class period, to share the work we have completed, and to prepare for the coming project–and there is always a project to undertake.

There is a large library of books arrayed along one wall surrounded by comfortable chairs. There are a few computers set on a standing bar; there is a widescreen TV on one wall. There is a stage set up with a green screen and mics and lights; there are two alcoves set up as recording studios–but there is no pencil sharpener; there are no reams of paper on a shelf; there are no blackboards or whiteboards, or posters hung on the walls–only guitars and banjos and framed artworks. There is–and there has not been–any paper shared between myself and my students for over ten years. Paper is simply not needed and, for me at least, is simply an inefficient hindrance to the work we do.

For many teachers, the classroom seems like an anathema. The lack of paper seems foolish and unwise. The distractions of technology mixed with students plopped upside down and sideways on the floor and across the arms of comfortable chairs is more than they can handle. Few teachers are jealous of my room, yet I guard it jealously–though I am very eager and willing to share it (and the secrets it holds)–freely and openly.

There is a great fear that real teaching and real learning cannot happen in a room where motion, action, and relaxation intermingle–where sitting takes a distant second to standing, where reading and writing on iPads, tablets–and even phones–is encouraged, where every essay is turned into a video or a podcast, where a blog post is recreated in a multi-media portfolio, and where everything is shared with each other, oftentimes created with each other, and always respected by each other. I

If I sound like I am crowing like a rooster at dawn, I am; and I will keep on crowing until one of my students says, “This is too easy,” “I’m not learning anything,” or “You really should get another job.” I will keep on crowing until a parent can sincerely say, “My child did not learn enough or write enough,” “Where is the rigor or basic skills my child needs?” or “What a waste of a year my child had in your class.”

If I have not crowed so loudly as to turn you away, keep scrolling and let me show you what I mean and how this approach can work in any classroom. I have the gift of a well-created classroom, but the essence of what I am trying to do could be accomplished in my backyard in a circle of pumpkins. The site right now is a work in progress, but please contact me you have any thoughts that can help me continue to build on this approach and, as they say, “Make it better.”

Have fun and “give a damn…”

Doing something which is “different” does not come easily to most of us. The wrestling team I coach will look at me sideways if I ask them to practice cartwheels. I’ve even heard that some professional football teams bring in dance instructors to teach their behemoth linemen the art of ballet and foxtrot. My point is that practicing “any” athletic sport develops your skill in another seemingly unrelated sport. The same is true in writing. Through practicing the skills and techniques used in different genres of writing, we can enhance the overall quality and effectiveness of the writing we love to do (or are required to do because of schoolwork or employment.) By practicing different styles and genres of writing, we learn to avoid the rut of developing a formulaic, predictable, and downright dull writing style—plus, you might even discover a renewed love and energy for a “new” kind of writing when you practice writing in an unfamiliar genre.

Over the course of the next few weeks, try and write in each of the following genres and styles of writing. I will post more detailed descriptions and writing prompts that span the many different types of writing, but it is up to you to give them a full-hearted try. Good luck and have fun!

1. Your Daily Journal: Every good writer keeps a journal that remembers the daily events of his or her life, no matter how mundane or common. A daily journal is a recording of your life as live it, and as such, it is a treasure trove of memories that you can draw from later in life—memories and snapshots that you can expand upon in a more formal writing piece any time you wish.

2. The Ramble: The Ramble (often called ‘free-writing’) is close related to the daily journal, but it is more of a free-flowing series of thoughts, ideas and experiences. It is a journey with your mind and heart and soul down an emotional and intellectual highway. The ramble does not have to have a formal structure, but it does try to find and focus on a specific theme, and it does try and punctuate and paragraph to the best of your ability. By defining a certain post as a ramble, you are freed from all criticism of your writing style and technique because you are simply on an exploration of yourself, and as such, it is hard to go wrong! Rambles are great fun and an invigorating exercise in writing, but it is what it is. Kerouac aside, it is a misnomer to call a ramble anything but a ramble. I have had many chagrined students who tried to pass off their ramble as a thinly disguised essay.

3. The Personal Narrative: Personal Narratives are the stories of our lives. By habitually practicing the art of storytelling through personal narratives, we practice the basic craft of the Short Story and the Essay. By telling the stories of our lives, we follow the main rule of all writing: write about what you know! I could write all day about the joy of Bungee jumping, and I still couldn’t convince a toad that I knew what I was talking about. But if I wrote about the day I watched people bungee jumping off a bridge, then I could probably get that toad to publish the story for me. I could be the protagonist, and my best friend forcing me to try could be the antagonist; fear of jumping into the unknown could be the conflict; standing up to my friend could be the climax; falling out of a tree when I was young could be my supporting facts; facing and trying to overcome my fears could become the theme of my essay/story, and when a reader can relate to your theme, they are able to recreate your story in their own imaginations. It might force them to think about their own fears, and in doing so, your story effects a powerful transformations in their lives. Every day and every experience is a possible personal narrative. If that experience means anything to you, it will mean the same thing to someone else because we are all tied together by our “common humanity;” we share the same emotional connections, but how we experience those emotions is infinite and infinitely varied—and that is why our libraries and bookshelves are filled, and that is why we all keep returning to the power and creative magic of literature. Think of everything you write as true literature.

4. Memoirs: The way in which a person affects your life is a profound statement of your values and an enduring testament a specific person’s influence on your life. A memoir is a type of personal narrative that paints a vivid portrait of an interesting and worthy character. Through images and actions, thoughts, feelings and memories you, as a writer, recreate the power and magic of someone who has left an indelible mark on your life. Every good novelist and short story writer is a master of the memoir because writing memoirs is the key to developing dynamic, real and empathetic characters, without which a story falls flat on its face!

5. Short Stories: Every writer is essentially a storyteller, but the craft of short story writing requires a discipline and attention to detail that most writers are not willing to undertake. A good short story effectively creates a powerful experience for the reader out of the writer’s imagination and experience. Most beginning short story writers bite off more than they can chew; they attempt to scale a high peak without first learning how to tie their boots. I will write more in a future post, but for now keep it simple: don’t write stories with a bunch of different characters. Two or three characters is all a good short story needs! Make the plot easy to follow, and be sure that there is a clear protagonist and a clear antagonist and a clear conflict. Most importantly, create characters that you can relate to on a personal level. If you are ten years old, make your main character a ten year old, because that is what you know best, and you can recreate experiences for your reader that are compelling and real. And remember that your first draft is never ever your best draft!

6. Poetry: Poetry is the highest art. A great writer is not always a great poet, but a great poet is always a great writer. Poetry is the hardest genre to pin down and say, “This is poetry!” Poetry is the rough gem of life polished to perfection. To write poetry, you need to simply ask yourself: “Why is this a poem?” A poem is more than thoughts expressed in short lines; it is the meticulous crafting, choosing and placing of words, lines, spaces, breaths, and stanzas that defines what you call a poem. This is all up to you as the poet. I can’t tell you what is and what is not a poem, but I can tell you that good poets read the poems of other good poets, and they spend huge amounts of time on their own poetry. With practice comes skill; with skill comes perfection, and poetry will only happen in this order. The first skill of a poet is to ask, “Why am I writing this?” The second skill of a poet is to ask, “Did I tell my reader something, or did I lead them somewhere and show them something?” Don’t give the meaning of a poem away, but do leave clues for the reader to find that meaning.

7. Personal Reflections: I love personal reflections. There are few joys greater than the opportunity to just “think about something.” At the highest level, a personal reflection is an intimate and high-minded conversation with our own self—a conversation that is focused on a particular subject, topic or idea. The personal reflection differs from the ramble because it refuses to jump from thought to thought. Like a ramble, it retains the “I” in the voice; however, it stays fixed on a theme that is expressed in some kind of thesis or guiding statement. It is, by nature, less formal than a topical essay by retaining a spontaneous and unaffected narrative flow that feels to the reader like it is coming directly from your heart. It always has a distinct beginning, middle and end, but it never loses the sense of an open and inquiring mind on a search for truth—and every one appreciates someone who is willing to explore their own assumptions. I often tell my students that a reflection explores the question, while an essay answers the question. A personal reflection asks of each of us: Why am I writing this? What am I writing about? What do I think about my topic? If I come to a conclusion, how did I get there? A well-written personal reflection is as powerful as writing can get; it is the best of your mind offered to the reader as a gift that the reader can share in, think about, and agree or disagree in equal measure. A personal reflection is the best of your thoughts distilled into an experience of words!

8. Literary Reflections: Writing without reading is like an egg without a yolk; the nutrients are there, but the flavor is lacking. Usually, when we finish reading something, we put it away on the shelf and convince ourselves we are impressed, amazed, indifferent, or profoundly moved. The literary reflection is an offshoot of the personal reflection because it does not try and criticize a writing piece solely on its literary merits, but rather it “talks” about something you have read purely on an emotional and intellectual personal level. There is almost no reason to write a literary reflection about something which you didn’t like reading. (That is what a “Review” is for!) Write Literary Reflections about literature that you feel is important for other people to read because you want them—your readers—to experience the same magic that you experienced. It’s like being on a sightseeing whaling boat and someone shouts out “There’s a whale,” and everyone turns to see the whale for himself or herself! They all appreciate your attentiveness, and in turn, you are pleased to point out the magnificence of the moment to them.

9. Reviews: One of the cool things about being in a writing community with your peers is the chance to write about and read about a whole assortment of books, movies, places, games and any other activity people your age love to do. We live in a world of reviews. We avoid movies because they get panned in the Boston Globe. We refuse to eat in a certain restaurant because it only has a three star rating in Gourmet Magazine. What many “reviewers” fail to realize it that what they write directly impacts a person’s very livelihood. The main job of a review is to tell your reader whether or not what you are reviewing lives up to the hype. If somebody is arrogant enough to say they are the best in town, then by all means, hold them to that standard. But if Al at Al’s Diner says he sells cheap burgers, it is up to you to tell us just how cheap his burgers are—and you might want to add in that you get what you pay for. I love reading reviews, but I insist they be honest and fair. Use common sense when writing a review: don’t give away the plot and ending of books and movies; don’t write a review about something someone else can’t experience. (That is what a personal narrative is for!) Make sure to balance out your reviews. If your reviews are all negative, you will soon get the rep as a negative guy; if your reviews are always positive and glowing, people will think you live in la la land.

10. Expository Essays: Everyone likes to be right, and the expository essay is the perfect vehicle to define what is—and what is not—right and true! The word essay comes from the French word, “essai,” which means “to try.” A good essay tries to defend a certain point (called the “thesis”) using logic and supporting facts, not personal opinion. You can’t say in an expository essay that the 2008 Celtics are the best team in history because they make you feel good about yourself (great for a personal reflection) but you can say they are the best team in history because the Celtics are the first team to go from last in the league to champions in a single year!

The Art of Collaboration

Danny, Jimmy & Me

I

Mrs. Roeber never seemed to let Jimmy go outside, which, to my thinking as an 11 year old, was why he was so smart. Most days after school, I’d rush two houses down the street and get Danny Gannon to come out and play. Then the two of us would go to Jimmy’s house next door. If Mrs Roeber answered, she would always be polite and say something like, “Jimmy needs to catch up on some science work. Perhaps he can play later.” If Jimmy answered, he’d usually be out of breath from running upstairs from his basement “office” and plead with us not to give up on him—or at the very least go out back and talk to him through the basement window.

So me and Danny would sneak out back and lay on our stomachs on the pokey grey gravel outside his basement window. Five feet below, Jimmy would be doing his work at his workbench (which, in all honesty, was a pretty cool place). I always wished I was smarter, so I could do his work for him and get him outside to play. I was better than Jimmy at a lot of things, but those things never got graded, and most of those things you couldn’t appreciate until “later in life.” But, to my Tom Sawyer way of thinking, I preferred being outside and average to being inside and smart. Danny was an outside kid, and smart, too, and that always troubled me, but not enough to let it call my inside/smart: outside/not smart philosophy into question. Danny’s voice was always the one that tried to tell me that the sledding jump was too high, or that branch would not support my weight, or those snakes would bite, or that we couldn’t run faster than a nest of bees we just destroyed.

Once we got Jimmy outside, he was like a mad scientist: ”We’ll, just have to see how high Fitz can go on his sled,“ or, ”I’ll distract the snake so Fitz can grab it from behind,“ or ”Bees have been clocked flying at 80 miles per hour.“ Looking back, we probably seemed like the gang that couldn’t shoot straight, and we did tend to go our different ways as we grew older, but we always still manage to reconnect somehow, and it doesn’t seem like we are a day older. It’s kind of hard to put into words because Danny and Jimmy might not be the best friends of my daily life, but they will always be the best friends I need.

Just thinking of the three of us together is like a window opening to a cool and welcome breeze. And the coolest thing is the window is always there. It might be that the only thing we actually had in common was living next door to each other, but still, we made it work; we made it real, and we made it last.

No choice. No problem. We did it together.

II

Life was pretty simple with Danny and Jimmy and me. There was no forethought in doing things together. It was more just some manifestation of a primordial DNA strand that we responded to with a visceral enthusiasm bordering on mania. We are born to be tribal in nature. We expect and need to be a part of a community, for we know in our bones and marrow that we really can’t go it alone. There is no Huck without Jim; there is no Odysseus without Athena, and there is no you without some hand that will pull you out of the muck you have made of your life. Thank God for the primitive man patiently stalking some larger prey to have the primitive women scrounging for tubers, berries, grains and millet, which no doubt provided the greater sustenance. We live and breathe a collaborative atmosphere of trust and unfathomable magnanimity.

Then why I did I always hate group projects, but, more telling: why did I change my mindset and my actions?

I hated group projects because they never seemed like group projects. What seemed in theory to be group work was really like some industrial factory spewing its incessant belching of traditions with an unequal and unsatisfying distribution of work and wealth, where the smart kids continued to be rewarded the lion’s share of honors, while the poor students (myself especially) continually paired themselves with a misfit tribe of friends who accepted the inequities of the classroom as a normal and an immutable reality of life.

Danny, Jimmy and I went to the same schools: Jimmy was—and still is—brilliant beyond my wildest dreams. Danny, too, seemed way smarter than me and probably smarter than most of the smart kid, though tempered with a shy and steady reserve (which by teacher default kept him from the brilliant crowd) that often forced him into our regressive and unrepentant tribe. As close as the three of us were in the ecosystem of our townie neighborhood, our schools erected barrier after barrier to keep us apart. While in school those walls did an admirable job of keeping us apart, and so we were only able to collaborate in our feral joys outside of school. Jimmy was smart, but not arrogant, and never willingly sought the tribe that formed around him, for when the academic birds of a feather were called to gather together, he was soon surrounded by the peacocks and strutting roosters of Concord, all brilliant in their own ways and inclinations, while my tribe and I wore our B’s and C’s and D’s like gang tattoos on our bruised and battered torsos.

Really, not much has changed between now and then, and while kids nowadays are more polite and empathetic, and at least begrudgingly inclusive, the iron curtains in our classrooms are still there–just more subtly erected. The academically accomplished kids are almost insanely driven to preserve the status quo—and if paired with the less accomplished, they will go to extreme lengths to do all of the work themselves. They do not want their brilliance to be diminished by including the less accomplished, less fortunate, and less able, and they will labor far into the night to correct the sloth and ineptitude of their partners. Ironically, it is an ignominy that they will suffer in silence, mostly because “collaboration” is part of the rubric—and in the end they all need to say it was a collaborative effort, and kids like me who simply sprayed the red paint on a smoke-spewing model of Mount Vesuvius remained mute in the complicit code of silence that dictated our lives.

So the rich preserved their wealth, while the poor squandered the chance to make a mark on their yardstick of time. The paradigm was set long ago: one law for the rich; one for the poor. It always seems strange and telling that the rich suburban and private schools constantly tout the quality of their students and teachers, when in reality that are just exposing the “quantity” of wealth and resources at their disposal. It used to piss me off, and I was satisfied in a smug way that at least I saw through the smoke and mirrors, until a point in time not long ago when I realized that, as Jesus said, “There will be poor always,” and I just needed to redefine what wealth really is and how it is spread around a classroom. I needed to unearth the inherent wealth in every kid I taught and see every one of my students as a treasure trove of possibility and make everything they did together engage that same passion of Danny, Jimmy and me hucking stones at bee’s nests. Every kid has to have a pile of stones to throw at the nest and the legs to run as fast as he or she can; otherwise, there is no skin in the game, no shared risks—and, ultimately, no shared triumphs.

III

Every classroom in every school on the planet is a blessed mix of possibilities—rich or poor, enriched or impoverished—with a mix of talents, drive, will—and more than a share of abnegating responsibility. As a kid, I hated group projects, and this hatred has fed my myopic biases for the past fifty years. They sucked as a student because I was never a full part of the group—and as a teacher, the group projects sucked because I would see the same inequities I despised perpetuated in my own lame assignments. I kept unleashing the same monster that swallowed me in my childhood. I was stuck in the stream of my own inbred traditions, though convinced I was nobly doing my duty as a teacher.

My epiphany came when I realized that I never really taught what the word collaboration means. None of us can grasp the wisps of what we don’t understand, but I had aways just assumed that we had a common understanding of the word—to do things together (whatever that really means) but while reading and teaching Moby Dick with my ninth grade classes, I found myself one day discussing the crew of the Pequod—and what a wild mix of nationalities it is: native american harpooners, dreamy adventure seeking deckhands, carpenters, sail menders, lookouts, blacksmiths, cooks and mates all bound up in a common adventure. Roles were defined, but in the fray of the chase every man took to the boats towards a common and fathomable goal. And what a success it was until the monomaniacal Ahab stepped to the deck and pointed the Pequod in his obsessive direction—to kill the White Whale. What was collaboration became duty and fate.

In discussing that twist of the plot, we started a conversation about what collaboration really is, and by the convolutions of discussion, we extended the metaphor of Moby Dick to help us define what is meant by collaboration. Collaboration is a shared adventure with shared rewards wherein every person is due his or her rightful share—the share agreed upon before setting foot on deck. No collaborative effort is inherently equal, for our skills and strengths on any given project are too disparate—nor will the rewards ever be the same for we will alway reap in proportion to what we sew and tend and what we sign on to do—but the journey and the chase can and should be exciting and rewarding for everyone, and no one person should ever be allowed to alter the common purpose of the voyage, and every person has to accept the mundane roles on quiet seas and rise from the forecastle when all hands are needed on deck, and every man has to drop everything and pull on the oars in precise rhythm when chasing the whale—and, most importantly, every person needs to be on that ship for the length of the voyage.

The Pequot’s crew was hoping to sail home to Nantucket with a belly full of oil that could be measured and assessed down to the last drop, and every part of that motley crew would know and expect, and receive a fair share of the reward.

So now I not only love group projects, but I believe that they are the heart and soul of my classroom. They are what binds us together as a community. They are opportunities to share strengths and work through weaknesses and differences. They help us recognize and respect the dynamic power of uncommon backgrounds pushing towards a common dream—not merely a goal. They help individuals find new and deeper sources of strengths that he or she never fathomed before.

But collaborative projects are not all roses and perfume. As a teacher you have to accept that it will take twice as long as you planned, and if you can’t be flexible, you are no better than Ahab—while at the same time your students need you as a captain who is stern and unforgiving and expects duty to be dutiful, who gathers the crew on deck when need be and frees them to their chores without being meddlesome, and when the blubber of the whale is being boiled down in the tryworks, your classroom will be a bloody mess. And just as in life, people will bitch and moan and convince themselves that their individual effort and persistence is what is keeping the boat afloat–and if that happens, call the crew on deck again–and again if needed. True collaboration is an honest day of hard and dirty work, not a bunch of friends trying to pass off sloth as substance.

And well all is said and done, and your students are tired, bloody, and bruised, give them their fair share of the split—and reward them, damn it, reward them.

Teaching Traditional & Modern Skills for Reading, Writing, Creating & Sharing in a Digital World

Create a Better Classroom

for You & Your Students

Teaching Traditional & Modern Skills

for Reading, Writing, Creating & Sharing in a Digital World

Video Essays

Creating video essays out of traditionally constructed essays bring a whole new dynamic and range of possibilities for every student. A hard wrought and well-crafted essay is no longer a static piece of paper tucked away in a teacher’s desk or stashed in a crowded hallway locker. It is a multi-dimensional project that is shared with the world. Check out some of these that were created by my eighth and ninth grade classes.

It’s Over: A Final Reflection

~Paul, Eighth Grade

A Trip with Thoreau

~Charlie, 9th Grade

A New Way of Creating Rubrics

No longer will the term “rubric” create dread in your students. The Crafted Word Rubrics are not checklists; they are guides to help students respond to almost any assignment in a clear and confident way.

Try them out!

The page you requested could not be found. Try refining your search, or use the navigation above to locate the post.

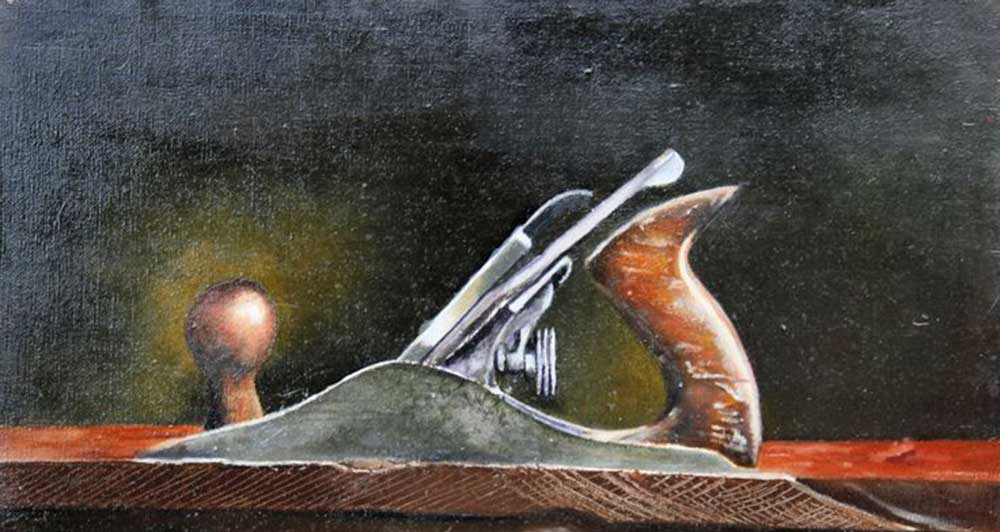

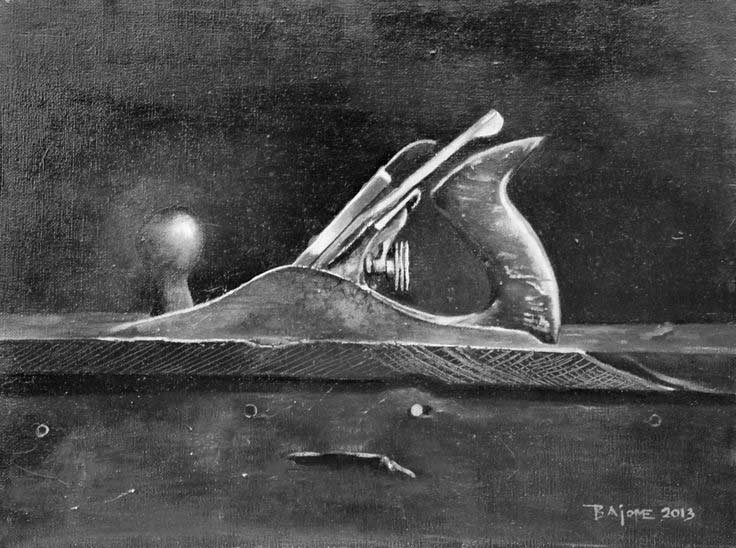

Few of us can do well if we don’t feel confident in what we are doing, but neither can that confidence be a misplaced confidence that is more succinctly called arrogance–a presumption of skill rather than an actual skill. Every time I create a teaching unit or plan a lesson–or even when I sit down to write something like this–I have to ask myself: “Do I really know what I am teaching, and am I teaching what I know in a way that all of my students are learning what I presume I am teaching?” I have to keep asking myself if I am the sage on the stage or the guide on the side; I have to keep asking if I am teaching essential skills and content or am I teaching what some reading workbook or English composition textbook says I should teach. Thankfully, at heart, I am still the shop teacher I have been for almost twenty years, but I am also the writer and teacher of writing I have been for more years than that.

Teaching shop is pretty cool because every kid comes into the shop with an untamed enthusiasm and eagerness to build something that is already in his or her head, and they are remarkably unfazed by their limited woodworking skills or by the scope of their dreams. I remember well an old student of mine who came into seventh-grade shop some years ago with detailed plans for building a one-man submersible submarine (as if you could build a non-submersible submarine:) and he begged me to give him a chance to try and build his design. Somehow he settled for something like a knapkin holder, but I heard the other day that he is now in Navy Seal training, so his ultimate dream never died; however, he learned that dreams can be realized and built out of a series of steps, an accumulation of skills forged out of the iron of real life and a dogged clinging to a vision of what he ultimately wanted to build.

Young writers (all writers) need that dream and vision, too. They need to love the possibilities that writing offers to build something as awesome and real as a six-board chest or a sparrow whittled out of a piece white pine. They need to go to the empty page with the same sense of possibility as the kid walking into the woodshop, and they need to want to learn the skills that will get them to a place they want to be as craftsmen and craftswomen of words and sentences and paragraphs and stories. Most importantly, they need a place and a way to learn and practice those skills: a workshop of their own to walk into and dream and learn and create.

Thoughts…

Thought…

How do you help teachers who are struggling to engage their students? How do you help teachers let go and grow and love and cope and change?

Points…

Reflections…

Writing an essay for me is relatively simple. I choose what I want to write about, and I start writing. There is not a soul in the world who is expecting anything out of this essay—or even know it is being created, which will be great if it dies an early and ignominious death. I don’t have a teacher pushing me in any one direction–like I am pushing you. The writing prompt and the inspiration is already in me; but, though I try to write well, there are no real-life repercussions when I don’t write well. My audience for this (which is you—my upper school English class) is remarkably small and polite, and as much as I’d like to think that you are captivated by my writing, I know that in reality you are a “captive” to my writing, because, as my students, you are a prisoner in my classroom. You are somewhat doomed to read what I write, but your actual freedom to write is hobbled by a teacher who is intent on extracting (by what must sometimes feel like any means possible) what you know and think about a narrow range of literature–in this case, the first chapter of Walden: the essay called “Economy.” Throw into the mix your other classes and what do you get: a few more books, an era or two of some history; some idea of why leaves turn red; a handy way discerning volume from the breadth and width of a fruit–a smattering of Spanish words or Latin roots: a bookshelf from shop and an abstract oil painting for your wall. Don’t forget your soccer and football teams, the school play, band, and student life, and now your day is completely filled.

But is it full?

It is certainly filled with an exhausting range of activities designed and structured to educate, enlighten, inform, and inspire. Your teachers are a diverse mix of people who really do give a damn about you and who spend more time than you might ever imagine trying to create and perpetuate this living and breathing machine called school, but, as Thoreau writes, “we[teachers and students] labor under a mistake.” We fill the day, but we rarely fulfill the possibilities of each day, and we never will until we remove the blinders that keep us on the beaten path. Frightening as it sounds, the lunatics must run the asylum: students must be allowed to take the reins and become learners and explorers, while teachers and administrators must adapt or die. “New ways for the new; old ways for the old.” (HDT) The world really is a different place now. The “noosphere” or “omega point” predicted by Pierre Teilhard de Chardin almost a hundred years ago is becoming a reality. People can be–and are–connected in ways unimaginable to the visionaries and teachers who broke the backs of tradition to create the schools we have today. But times have changed. The desk is more a ball and chain of myopic restraint, while our opportunities for true learning–for all of us–have never been greater.

Something has to give. Society and its schools have become as much slaves to assessment as we are creators of destiny. Measuring someone by “the content of their character” seldom makes it onto report cards. Instead, we measure your progress and achievements with a reptilian calculation of the merits and deficiencies of your responses to specific inquiries and lessons we are convinced we have taught well. We critique what and how you write, but rarely consider why you write. Though we seem compassionate and practice empathy, we still erect a barrier that only a few of you can get over unscathed–and those are the celebrated few: the smart, hard-working, and diligent students who somehow manage to do it all. Everyone else plays catch me if you can, and so this paradigm is set in motion, and it becomes the foundation of almost every school and university in the world. The gifted student becomes a recognizable icon, sculpted, shaped, and polished by the whims of academia. As parents we stumble over each other trying to weave our child’s place on the honor roll or his or her SAT scores–or even the average score of the whole town in comparison to every other school in the district–into the most casual of conversations. On the flip side of this coin, these honors are hardly as respected by peers and classmates (perhaps because they sense the inherent fraud and advantage to the system) and past prowess as a student soon makes for unsavory and indelicate talk even just mere hours after graduation.

Maybe doing well in school is not such an impressive accomplishment. It is pretty cool that we have a black president raised by a single mom–and we use this as praise for what educational opportunities can do; but history is full of great individuals who rose from humble beginnings. It is a recurring theme of humanity itself. It is part and parcel of what Joseph Campbell has termed “The Heroic Cycle.” Schools do not create greatness; our primal need to be great is what creates greatness. No one reading this is precluded from realizing his or her individual greatness. We don’t have to be Telemachus facing up to the rowdy suitors in his house, but all of us have challenges that are unmet and untested, and we must meet them and we must test them if we want to be a hero. There is courage and strength of each of us, but not as much motivation, perhaps because the tools we use in school are not the best motivators. We instill as much fear as desire, and there is a subtle paralysis that takes hold. Only if the doors open wider and the walls fall down will we see the expanse of our opportunities–and only if you give enough of a damn to reach for the dream at hand, and then only if you see the dream. Realizing your dream should be your accomplishment, and layering dream upon dream should be your life.

Life has a way of doling out hardship in unequal proportions, but school should not be one of them. There is certainly very little that is fair about who goes to what school, but that is the unspoken inequity. We praise the notion of an egalitarian educational system, but we shudder at the thought of implementation. Few of my Concord friends would ship their sons and daughters to our schools in Maynard because…well, just because. Ironically, few of my Maynard friends would feel comfortable with their sons and daughters trying to mingle in a Concord milieu. And so we keep up a pleasant caste system that feeds off the tension between the rich and the poor. It’s like the old camp song: “Don’t chuck your muck in my backyard/my backyard’s full,” but because of the internet, our backyards have merged; the demarcation line is blurred, and there really is a chance for every kid to play on the same field–if we let them. Caesar accidentally burned down the Royal Library at Alexandria; we shouldn’t do the same with our new library of knowledge. During the first solo circumnavigation of the world, the Afrikaners in South Africa scoffed at Joshua Slocum’s claims that the world was round, even as he was ninety percent of the way around the globe! Wouldn’t it be ironic if our schools lost the race for knowledge because we dithered at the starting gate?

I certainly did not start this narrative with any plans to take on our educational system. Sharper minds than mine could tear this essay apart, but only because they have had so many generations to practice. The hurricane yesterday gave me a rare gift of time today, so I was just hoping to give you a few words to help you get started on your Walden essay. Words have that effect on me. Maybe my own rereading of Walden made me listen more closely to the drumbeat of my heart no matter how measured or far away; maybe in these political times of gloating, bitching, and belittling I didn’t want to be one of the thousand hacking at the branches of evil; I wanted to be the one striking at the root. The beauty and bane of Thoreau’s words is how easily they can prove either side of an argument, and my mind is so scattered that I could never get around to organizing all the facts; instead, I’ve simply scattered some seeds among the compost of my experience. Hopefully, one or two will be like the mustard seeds in that parable of Jesus. If not, I’ll have to till again and plant more thoughtfully.

All I know is what I sense: change is coming, and if you have your wits about you, you will be riding the edge of that wave.

Few things in life are more important than having a passion for something. It is an offshoot of “give damn.” To have a life without a focus on some something or somethings to do and explore and develop on your own is a pretty pitiful life. When I was your age, I had a rock collection that filled a bazillion egg crates with chippings and scrapings I hammered off ; I had snake and reptile aquariums that had specimens of most any cold-blooded creature in the White Pond area of Concord. I had a shortwave radio that I made with my father–and a huge antenna on the roof to help pick up conversations happening anywhere in the world. I had a collection of fishing poles and rods and reels and lures and baits to somehow tease trout, bass, horned pout, kibbers, pickerel and anything else out of the Concord River, Walden Pond, the Assabet, Nashoba Brook and Warner’s Pond. Best of all my family had a plywood sailfish sailboat my father built in our garage from plans he got in somehow to magazine, and in that 12 feet of arc, I got my first taste of sailing–a taste that is as strong today as it was back then. My bedroom was a mess of magazine both strewn and piled–but always read: Boy’s Life, Popular Mechanics, Popular Science, Field and Stream, Sears Roebuck, National Geographics and any other magazine, book, or journal that fed my passions. Most of those publications are still around to buy in some way today, but there is an even larger world of bloggers out there who cover everything those magazines covered–and a whole lot more. These blogs and websites are where people go to feed their passions and develop their own knowledge and skills. It is where you go and where I go, and the better the blog or the better the site, the more often we return, and the more we return–the more of a mark that writer has left on the world. And that mark says something about that person. You. Something good, I hope.

In ancient Rome there was a saying: “De gustabus non disputantum,”otherwise known as “There is no accounting for taste,” which is a good thing because it keeps the world to this day interesting, diverse, and dynamic. We don’t have to like what other people like, nor are there any compelling reasons why we should–but we should like something; we should want to be knowledgeable about something, and be good at something, and to constantly be getting better at something. Think of your passions, and think of what you can do to live out that passion or passions and share it with the world. Think of what you are going to leave behind as your footprints in this life. You do not want to be like the drunk sailor Elpenor who fell off the roof and died a death that no one remembers or cares about. As Odysseus himself said: “No songs will be sung about him.” Your “digital footprint” is the song that is sung about you.

When I first started blogging with my classes–now close to ten years ago–most people were paranoid about kids names being “on the internet,” and so we built firewall on firewall behind private servers to keep you safe and removed from the real internet. In most ways it has been great. It gives you guys a safe place to practice living and sharing in the digital world without the dangers of anyone knowing you are out there. But times have changed. Soon you are going to want your name be out there–and out there in a good and positive way. You are not going to want someone to google your name and come up with…nothing. I am really proud to have discovered that it is relatively hard to study haiku and not come across my website at some point in your studies. I like that if someone googles my name they get the best of me and not the worst of me. I want that for you, too.

If you’ve got a passion, then keep learning and practicing and experimenting, and then share it with the world. If the seed dies with the flower, there is no beauty left behind.

Thoughts on Assessment

Assessment is a terrifying word. I know my students fear it is just a softer term for the harshness of grading–an even more terrifying word, but if we do not assess everything we do, we become the proverbial bearers of repeated mistakes. There are few things that tick my students off more than to get a grade that seems pulled out thin air, riddled with inconsistencies, and is more punitive than enlightening or helpful—but grade we must. It is the Sysyphean chore and duty of every teacher—but does it have to be? Do we teachers have to be final arbiters of fate in this regard? Is there enough room and the grading house to allow the students in? Do our students have to always live like criminals turning themselves over to the authorities for every miscue and misdemeanor in their academic lives—and short of perfection, it seems to be their lot in life. But, if we do not let them in, and if we insist on being their judge and jury, we have squandered the greatest skill they need to master—to be able to to deconstruct their efforts with clear eyes, moral candor, and infinite hope of betterment. In short, let our teaching teach how to assess. Invite students in and let them share and dialogue and assess with us and with each other.

Research shows that we retain little of what we hear in the classroom. The odds increase somewhat (though not dramatically) when we also read what we are supposed to learn; however, learning increases dramatically when we need to present what we learn—and even more dramatically when asked to teach what we have learned. My own students know me as a bit of a pious bear when it comes to learning punctuation; however, as soon as I get on my podium and start talking about punctuation, the room is soon filled with what I call “grammar gas,” which always—as in always—works its way into the very souls of my captives until even the most focused, grade grubbing scholar fades from view and into their own solipsistic reveries—and sometimes simply slip into a hypnotic trance that actually mimics paying attention.

But (the proverbial “but”) when I free them to practice punctuation by watching my videos or laboring through interactive self-grading quizzes and worksheets, they will work endlessly until every single answer is right, and they will then strut around the classroom proud as peacocks to pronounce victory over a dreaded foe. The underlying magic in this approach is that they “see” what they need to do, and while they will never use the word “assess” they are actually living the experience of assessment. They have control of their respective destinies, and they intuitively know where and when they are screwing up and what they have to do to rectify the screw-ups. Putting these newfound skills into future writing pieces is another ballgame, but at least when that red pen circles the comma splice, they are the ones to take the blame, and they can look deeper into themselves for a solution instead of lamenting that I was grading them on something I barely taught!

During exam weeks, I am always amused by teachers who proclaim that no one in their class got higher than a C on his or her exam, as if it were solely the fault of the lazy students who did not prepare for the exam. I bite my tongue and never actually say that they had the whole year to teach what was on the exam. I shudder to think that my back surgeon needed to cram before boring into my spine with a drill! Knowledge needs to be organic. It needs to grow from a well-tended garden fertilized by a continual attention to what makes the fruits and flowers blossom and grow—but instead of a garden, too many students finish the year trying to make sense of a weed-patch of information until they hardly know the weeds from the crops. We move through our curriculums as if driven by a dark force that knows no other way. We teach. We assign. And we grade. And the vicious cycle leaves little room for true and effective mastery. We give what we think is helpful feedback and helpful criticism, but more often than not it is simply degrading commentary that diminishes more than it develops. None of us needs to be assessed more than we—students and teachers alike—as the creators of our works need to assess with skills and techniques that are helpful, hopeful, effective and practical in sustainable ways.

I am better at pontificating than problem solving, and I am loathe to have anyone come into my space and tell me what I should and should not do in my class. I am amazed every day by the sheer dedication I see in my colleagues in preparing their curriculums, grading great sheaves of papers, meeting with lost and wayward students, and easing the minds of over-anxious parents. But we are prey to our own inertia in all endeavors of life, and we need to rethink and retool the grading paradigm and channel our limited energies towards teaching students how to assess and how to move forward after assessing his or her work.

The bear that lurks in the corner of every classroom is the beast of time. No sooner has one task been completed when another rises from the ashes. The lesson planner becomes the tail that wags the dog, and to paraphrase Thoreau: we do not ride the railroad as much as the railroad rides upon us. Our destination is distant and our direction is fixed. The very notion of giving time to students to asses and reflect upon their work is a path fraught with peril and ambiguities, and so even the most well-intentioned and experienced educator is caught in the tangle of duty, obligation and tradition—and ultimately the energy for transformative change remains more dream than reality.

But you can’t jump a canyon in two jumps. We need to make the decision to change the way we grade, and our students need to learn to assess their own work in practical, pedagogically sound and sustainable ways—and we need to make the leap, or at least some of us have to make the jump, if only to show what is possible. All I know is that a good portion of my life is spent reading, marking up, and grading essays. In the crunch times of the year, this amounts to several hours at night when I should be watching NCIS with my kids. It’s crazy, as it seems we grade as if we are the ones being graded—and we are! These marked up essays make their ways into the critical banter in the hallways; they fall into the hands of parents who will dissect and parse our responses more than their children’s work, and we become the fodder of their disdainful gossip. In that sense, my way of grading works. I receive relatively few complaints and more than a share of praise for the efforts I put in, but I no longer think I am doing the right thing. I need to focus on teaching, not assuming a role as sole assessor and arbiter of right from wrong.

In my nostalgia for times gone by, I remember my days as a shop teacher when my most anxious moments at night was to remember to pick up ten 2×4’s at the lumberyard on the way to school—but maybe the approach in the woodshop is a better way. When working in the shop, I never grade their projects; I grade the process of the creation, which certainly levels the playing field. Most importantly, a show student “knows” what the final product is supposed to look like. They work from drawings, plans, and blueprints; there is a logical and structure and sequence to the workflow, and they can palpably “see” when something is or has gone wrong. These bumps in the road are never a time for criticism—and the student willingly and eagerly seeks the help they need–but more of a time to “figure out” what is going wrong and how to fix it. The do not take the project home to work on the mistakes; they come to the next class ready to work through and overcome the setback. It is a lesson in teaching that can be built into any academic classroom.

The lightbulb for me is to do the heavy work in the classroom where a teacher has oversight of the process and approach—be it writing an essay, completing a lab report, compiling a presentation—or most anything! Homework needs to be what can realistically be completed at home and should be very specific to the needs of the work being done. With seven kids of my own, I have seen firsthand time and time again homework that requires to much processing time and not enough practice time. There is no reason that homework should be a source of massive anxiety, failure, and trepidation—it needs to be doable and calculated to take a certain amount of time, not a list which will take some 10 minutes and others thirty minutes, and it needs to be directly related to the work being done in the classroom. Now, when I assign thirty minutes of reading for homework, I make sure it is thirty minutes by providing audio that is thirty minutes long. If it is an essay or writing piece of some sort, I provide a detailed rubric (blueprint) for them to follow where I only expect a certain type of content not quality of content. If it something I want them to learn and practice by rote, I make sure it is measurable and limited using self-graded flashcard programs and interactive presentations and quizzes. If I grade any one piece of an assignment, it is the writing of a metacognition, which is a brief reflection on a students experience of the process. The refining of the content is always down in the shop…I mean, class.

I realize that to many teachers, my epiphany is no great thrust of genius, and it has been their common practice for years. It is a cornerstone of the flipped classroom, but it is certainly not an approach welcomed or practiced by the majority of teachers I know—some who are stubbornly clinging to the tried and true, some who sincerely disagree with me, and some who are too strapped for time to realistically rethink and retool what they do. The downside of my approach is the time and effort it takes to front-load the classwork and homework; the upside is a more empowered, confident and engaged student. Administrators would be wise to spend less time meeting with teachers and more time spent leading workshops and giving teachers the tools and time to develop and sustain this approach.

By doing the down and dirty work in the classroom, assessment becomes a natural and engaged action down with and through each student in an empowering and rarely punitive way. As teachers we need to see how and where a student struggle with our own eyes, mind and heart—and help them when needed, and we need to free them to figure it out when appropriate and, again, doable, which can only be done in the heady and invigorating dynamic of the classroom—the place where we as teachers have control and where out expectations can be carried out with a semblance of clarity and purpose. We cannot and never will be able to control the dynamic of the home environment. Never.

As always, I drone on. Sorry, but I get pumped just thinking of the possibilities of teaching that are more profound and enduring. Changing my ways (stubborn as I am) was a leap across a wide canyon, but the view from the other side is a pretty awesome view.

To assess is to progress. It is that simple.

Digital Damnation

As teachers, it is critical that we teach our students how to leverage the power of the web to create, cultivate, and curate positive digital footprints in and out of the classroom; moreover, as mentors and role models, we need to do the same. We need to put into action best practices, wise pedagogy, and a well-rounded understanding of the implications, promises, and potential to show thoughtful leadership and take control and realize the dynamic and transformative possibilities of our presence not the web.

Someone is not just looking for you; they are searching for you, and you are only one one regrettable statement or stupid posting away from your judgement, and hence your character, being questioned by an admissions committee, potential boss, or anyone else casually (or intently) searching your name on the web—and it is going to happen! The irony that the only thing worse than a questionable digital presence is no presence at all. While there is some nobility in being off the grid, there may also be precious little else to set your particular genius and passion apart from the masses that are arrayed beside, before and behind you. A powerful and compelling digital portfolio puts your proverbial best foot forward. Your digital portfolio collated and curated over the course of years makes a powerful statement of who you are, what you value, and what you have accomplished. A digital portfolio shows that you give a damn, and that you have been giving a damn for a long time. And that is a powerful reflection of your inner character, your persistence, and your values.

We must teach our students how to leverage the power of the web to create positive digital footprints. We need to put into action best practices and wise pedagogy, to show thoughtful leadership and an understanding of the pitfalls, promises—and potential of digital classrooms by taking control of our digital footprints (and our student’s digital footprints) and harnessing the transformative possibilities of an engaging, and forward-thinking digital curriculum. I will share how ten years of my teaching using blogging communities, online assessment, and ongoing portfolio creation has transformed a generation of teenage students into eager, confident, and capable writers and readers.

I will demonstrate how an online, blog-based curriculum works on a practical and philosophical level to create amazing writing pieces, podcasts, video essays, discussions, and multi-media content, and how students can use blogging platforms, compelling portfolios, and focused social media to avoid digital damnation by creating, collating, and curating an informed, powerful and positive digital footprint in an increasingly connected world.

Appophobia

Appophobia: (n) A lingering fear and distrust of apps

Always do what you are afraid to do.

~Ralph Waldo Emerson

We have evolved into what we are because we have somehow learned to balance mistrust and wariness of danger with a counterbalancing willingness to explore and exploit the rewards of equally dangerous undertakings and adventures. The stories of our histories would be tepid and soon forgotten if not faced with struggle and perseverance that somehow revealed a greater truth and wisdom and courage to live in a higher state of existence. If we do not accept and embrace this, then we may as well just relegate ourselves to a more diminished and ignorant self. Mighty high sounding talk, I know, to lead into a discussion of apps on an iPad.

But, it is what it is…

Every folder on my iPad is essentially a toolbox where I keep useful tools. I never let any one toolbox contain more tools that can fit on the cover screen of any folder—usually something like 12 apps, most of which I seldom use, but some that are essential to my daily workflow. It is no different than the toolboxes a I use when teaching shop or managing the various projects I undertake at home.

I have a toolbox for plumbing supplies and tools. I have a toolbox for painting supplies. I have a toolbox for woodcarving. I have a toolbox for working on my car and bus and boat. All of these are kept in my workshop and in my shed along with benches, shelves, vices and hooks and hangers.

Not once has someone said to me: “Fitz, you have too many tools in too many boxes in too many places.” I simply have what I need and what has evolved to serve the purposes and tasks of my everyday life. And still I sometimes have to go to Tom Cummings shop or a friend’s garage or another friend’s shed to “borrow” what I need, but don’t have.

So why the incessant hubbub I hear about too many apps on a student’s iPad? If they are useful to him or her—or me as their teacher—it is a useful app, regardless of how often a specific app is used. My shop students routinely come to a shop filled with all manner of tools—most of which those students are clueless about how to use.

And the funny thing is that it never seems to bother them or their parents or the school because everyone intuitively trusts that what is there is a useful and an ultimately necessary part of a dynamic and well-equipped shop.

And many of them are extremely dangerous tools! Way more dangerous than GarageBand, Book Creator, iTunes U and iMovie. This appophobia is as senseless as it is crippling, and the clarion call to forbid these apps is being led by people who have no clue how to use and exploit these tools for academic benefit.

The usual fallback for declaring an app to be useless is to lament that learning new apps is confusing and distracting and the sign of an out of touch teacher. With that logic we should throw out quadratic equations, the krebb’s cycle and the causes of The Civil War, and the proper use of conjunctive adverbs. We should ban backpacks with more than three textbooks, any loose sheaves of paper and calculators with any kind of trigonometry functions. We shouldn’t give a lecture that is more than five minutes long or occasionally ask kids to just remember the assignment—as in just remember the conversation we had at the end of class.

Imagine the horror of so many when the first pencils with built in erasers tumbled off the assembly line. Mistakes could now be hidden with a simple flick of the wrist. How could teachers even begin to know what students did and did not know? Imagine a school allowing students to use textbooks to supplant the power of a teacher’s oration on any given subject matter?

Education is like a shark: if it does not continue to move forward, it dies. If education does not move in the direction of its prey, it ultimately weakens and dies. If we put myopic restraints on a teacher thing to put new and dynamic power into the hands of his or her students and forge a new and better way of learning, then education dies. No fish can ever be caught without stirring the waters, so we should embrace the messiness of learning as the tailings of a miner’s labor.

Which brings me back to this iPad of mine tapping away in the stillness of a late September night. It is my poets hoe, my pick axe, chisel and plane. It is doing what I need it to do at this given point in time. In a few minutes (I hope) it will be the final chapter in a good book. Tomorrow it may record my songs, film my video, craft my essay, fill my journal, create my quiz, model my discussion, post my assignment, paint my canvas, grade my homework—and when I don’t want it or need it, or feel if is useful, it simply disappears.

Back into my shed, my toolbox, or some dusty shelf…

The iPad is not a tool or a device or a thing. It is an enabler of possibility. Apps are not a panoply of evil undertakings; they are merely shovels and spades that let us dig deeper and faster and cut our corners as clean and square as Mike Mulligan and Mary Anne.

And I do not have a problem with that.

Don’t Do It

I was eighteen and designing a production line for making stepladders at Fitchburgh State College—the only college I could afford, and probably the only place that would have me. I remember thinking, ‘Man, this ain’t no life for me.’ I barely had a working idea of what life meant, but I was pretty sure it meant I didn’t have to do something without any meaning or purpose—and I certainly didn’t want to spend my life designing a better stepladder.’

But, what did I want to do? Did I have the courage to even make a change in my life? If I had read The Odyssey, I might have known what to do; I might have known that I was on a heroic journey and that my call to adventure was the churning confusion in my gut, and I might have known to look for a helper and an amulet to get me over the threshold—that no quest is real until you realize that you cannot go it alone.

My helper was my English professor. I can’t even recall her real name, but she was old and sweet, and so we called her Aunt Bee—and she was sweet enough to ask me to stay after class to meet with her one day early in the fall. (Although I was petrified she was going to have me expelled for charging five dollars to any kid in my dorm to write their English papers for them.)

Instead, she held a paper in her hand that I had written, and a paper in which I actually cared about what I wrote. The day before she had told us to take a walk through the city and then write about the walk. Most of my classmates stayed in the dorm, laughed about how naive Aunt Bee was, and wrote some insipid scrawls that they thought would qualify as an essay—or they tried to get me to write an essay for less than five dollars.

But I took the walk. I wandered through the poorest streets in Fitchburgh; I sat on front steps with little kids and old men; I sat with drunks and dreamers, and I wondered. I wondered if my walk was actually real, or if I was even real, and then wrote some story about a kid who couldn’t tell if he was awake or dreaming or even which state of mind he wanted to live in. Aunt Bee shook this paper in my face and said bluntly, “You shouldn’t be an industrial arts major. This [shaking the paper even closer to my face] is your gift!”

Never once had anyone told me I had a gift of any sort, except perhaps for whittling birds out of scraps of soft pine. I don’t think Aunt Bee knew how ready I was for a change—any change. I seemed to take her off guard when I responded, “Okay. So what do I do?”

“Leave this place,” she answered.

So I left.

Never had a decision been so easy and so hard at the same time. It was easy because I knew in my heart that Aunt Bee was right, but it was hard because my parents thought I was throwing my life away—and I was: I threw my old life away and charted a new course into a world of words and literature—a world that I really knew nothing about.

That decision in 1976 is the reason I am writing this to you today. It has been the proverbial long and winding road, but I have never been let down by a book or hobbled by anything I wrote, even though much of what I’ve written is pretty dumb and forgettable.

There was very little academia in my new journey. I learned to write by writing. I learned to write better by listening to what people thought and felt about my writing. I joined some writing workshops where each week each person would bring in some poem or story to share with a circle of other would be writers. I learned what worked in my writing and what didn’t work—at least to the small universe of my writer’s circle. I never thought I was a good writer, and so I was never really bothered by what people said. I just thought, ‘Cool. I guess I should change this….’

Even after a few workshops, I still never thought I was a writer, until I one day a friend introduced me to his friend by saying, “This is Fitz. He’s a writer.” I protested that I was not a writer, and my friend just said, “Then what the hell else are you?”

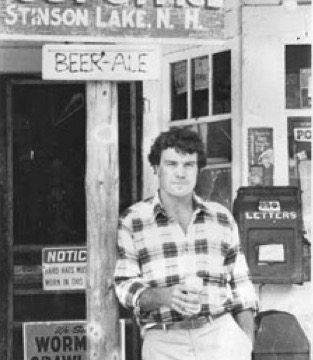

“I don’t know. An apple picker, I guess,” for at the time I was picking apples with a crew of Jamaicans in a New Hampshire orchard.

“At any rate, Fitz is a better writer than he is an apple picker. That much I’m sure,” my friend said, sealing the deal and sealing my fate—a fate which, by and large, has been good to me.

But be careful, for you, too, might become a writer; and once you become a writer, you can’t turn back; you can only turn away. Such is the power and allure of writing. If schools really knew what happens when a kid becomes a writer, they would ban the teaching of writing. It’s like giving a ten year old the keys to a bad-ass car; it’s like pointing across a canyon and screaming, “Jump!” It’s like opening the window and pointing in every direction and saying, “This is all you need to know and everything you’ll ever try to know.”

Writing is unfettered and audacious freedom.

Don’t do it.

So, you finished your “poem” in whatever genre of poetry you are writing, and you turn it in and proudly think, ‘There is no way any teacher can grade me down after I poured my heart and soul onto the page!” And you know, I do have a hard time deducting points from poetry. I know how hard it is to write good poetry that works for other people as much as it works for the poet itself (and yes, a published poet, after abandoning a poem to posterity, is an “it”) so I tread that fine line between encouragement and helpful prodding.

My solution is twofold: one, I ask you to write a metacognition that explores what you are trying to accomplish in the poem and how you do this. Second, I beg, plead and cajole you into going back to the poem like a wall builder goes back to a stonewall to see where the gaps are too large or the stones too small to support something as timeless as a wall. As poets, (unlike with true wall builders) there are plenty of stones laying around from which to find a better stone to build a better wall.

For those of you who hate my metaphors, this means to relook at every line and rethink every phrase and reexamine every word; otherwise, you have no right to call yourself a poet. A

In practical terms, this means to look at how your words power the poem. Are you simply trying to convey an idea or thought, or are you manipulating the actual words and lines to create an effect in a reader? Are you employing anything from the long list of poetic terms and rhetorical techniques that have proven themselves for, in some cases, thousands of years? Are you creating phrases—the literary equivalent of riffs and chords and bass runs in music—in ways you have never heard or seen before?

In short, do you give a damn?

If you do, do it.

If you don’t, it won’t.

The Power of Descriptive Writing

Tell Your Story

Our minds shift gears when filled with imagery: either we slow down and smell the flowers or we shift into a higher gear, and our minds become alive with the power and rush that only images and actions can initiate to such great effect—but either way we, as readers, are more alive, ready, and willing to move in a new direction. The writer who does not realize this runs the risk of becoming an erudite prude at best and a self-centered mouthpiece at worst because his or her words remain untethered to the real world of the reader who instinctively wants and needs to be anchored to a place that gives full breath and breadth to the senses. It is through engaging the senses that a writer engages the reader. To learn the art and craft of descriptive writing is to learn how to tell good story—and in the end, all writing is simply storytelling, good and bad.

Our minds shift gears when filled with imagery: either we slow down and smell the flowers or we shift into a higher gear, and our minds become alive with the power and rush that only images and actions can initiate to such great effect—but either way we, as readers, are more alive, ready, and willing to move in a new direction. The writer who does not realize this runs the risk of becoming an erudite prude at best and a self-centered mouthpiece at worst because his or her words remain untethered to the real world of the reader who instinctively wants and needs to be anchored to a place that gives full breath and breadth to the senses. It is through engaging the senses that a writer engages the reader. To learn the art and craft of descriptive writing is to learn how to tell good story—and in the end, all writing is simply storytelling, good and bad.

“This is such bull!” I can almost hear the academic writers crying out in opposition. “We are empowered by ideas and the synthesis and explication of these ‘thought provoking’ nuances of a brilliant mind working towards a solution of a specific and fascinating thesis…” Yeah, they got me there—but only if they got me interested in the first place; only if the tree of my life is already leaning in the direction of that thesis, and only if my mind is ready and willing to plow through the muddy slough that seems to be the field of what is blithely and blindly called “essays.” For me at least to keep plowing through, I need to be reached not only an intellectual level but also on the real and palpable visceral levels that completes the fullness of my being human—the blood, flesh, and bones that keeps the intellect alive. Good, descriptive writing is the vital core that captures not just the mind, but the pumping heart and manifest soul of the reader.