No Results Found

The page you requested could not be found. Try refining your search, or use the navigation above to locate the post.

Digital Damnation

As teachers, it is critical that we teach our students how to leverage the power of the web to create, cultivate, and curate positive digital footprints in and out of the classroom; moreover, as mentors and role models, we need to do the same. We need to put into action best practices, wise pedagogy, and a well-rounded understanding of the implications, promises, and potential to show thoughtful leadership and take control and realize the dynamic and transformative possibilities of our presence not the web.

Someone is not just looking for you; they are searching for you, and you are only one one regrettable statement or stupid posting away from your judgement, and hence your character, being questioned by an admissions committee, potential boss, or anyone else casually (or intently) searching your name on the web—and it is going to happen! The irony that the only thing worse than a questionable digital presence is no presence at all. While there is some nobility in being off the grid, there may also be precious little else to set your particular genius and passion apart from the masses that are arrayed beside, before and behind you. A powerful and compelling digital portfolio puts your proverbial best foot forward. Your digital portfolio collated and curated over the course of years makes a powerful statement of who you are, what you value, and what you have accomplished. A digital portfolio shows that you give a damn, and that you have been giving a damn for a long time. And that is a powerful reflection of your inner character, your persistence, and your values.

We must teach our students how to leverage the power of the web to create positive digital footprints. We need to put into action best practices and wise pedagogy, to show thoughtful leadership and an understanding of the pitfalls, promises—and potential of digital classrooms by taking control of our digital footprints (and our student’s digital footprints) and harnessing the transformative possibilities of an engaging, and forward-thinking digital curriculum. I will share how ten years of my teaching using blogging communities, online assessment, and ongoing portfolio creation has transformed a generation of teenage students into eager, confident, and capable writers and readers.

I will demonstrate how an online, blog-based curriculum works on a practical and philosophical level to create amazing writing pieces, podcasts, video essays, discussions, and multi-media content, and how students can use blogging platforms, compelling portfolios, and focused social media to avoid digital damnation by creating, collating, and curating an informed, powerful and positive digital footprint in an increasingly connected world.

Appophobia

Appophobia: (n) A lingering fear and distrust of apps

Always do what you are afraid to do.

~Ralph Waldo Emerson

We have evolved into what we are because we have somehow learned to balance mistrust and wariness of danger with a counterbalancing willingness to explore and exploit the rewards of equally dangerous undertakings and adventures. The stories of our histories would be tepid and soon forgotten if not faced with struggle and perseverance that somehow revealed a greater truth and wisdom and courage to live in a higher state of existence. If we do not accept and embrace this, then we may as well just relegate ourselves to a more diminished and ignorant self. Mighty high sounding talk, I know, to lead into a discussion of apps on an iPad.

But, it is what it is…

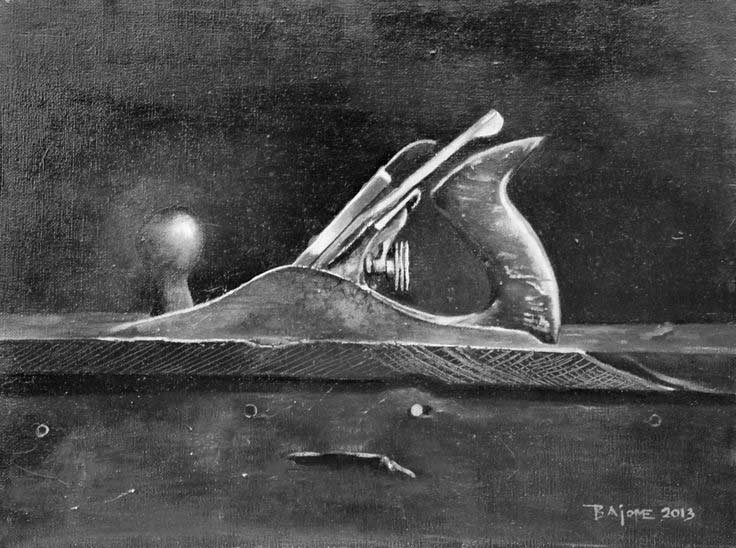

Every folder on my iPad is essentially a toolbox where I keep useful tools. I never let any one toolbox contain more tools that can fit on the cover screen of any folder—usually something like 12 apps, most of which I seldom use, but some that are essential to my daily workflow. It is no different than the toolboxes a I use when teaching shop or managing the various projects I undertake at home.

I have a toolbox for plumbing supplies and tools. I have a toolbox for painting supplies. I have a toolbox for woodcarving. I have a toolbox for working on my car and bus and boat. All of these are kept in my workshop and in my shed along with benches, shelves, vices and hooks and hangers.

Not once has someone said to me: “Fitz, you have too many tools in too many boxes in too many places.” I simply have what I need and what has evolved to serve the purposes and tasks of my everyday life. And still I sometimes have to go to Tom Cummings shop or a friend’s garage or another friend’s shed to “borrow” what I need, but don’t have.

So why the incessant hubbub I hear about too many apps on a student’s iPad? If they are useful to him or her—or me as their teacher—it is a useful app, regardless of how often a specific app is used. My shop students routinely come to a shop filled with all manner of tools—most of which those students are clueless about how to use.

And the funny thing is that it never seems to bother them or their parents or the school because everyone intuitively trusts that what is there is a useful and an ultimately necessary part of a dynamic and well-equipped shop.

And many of them are extremely dangerous tools! Way more dangerous than GarageBand, Book Creator, iTunes U and iMovie. This appophobia is as senseless as it is crippling, and the clarion call to forbid these apps is being led by people who have no clue how to use and exploit these tools for academic benefit.

The usual fallback for declaring an app to be useless is to lament that learning new apps is confusing and distracting and the sign of an out of touch teacher. With that logic we should throw out quadratic equations, the krebb’s cycle and the causes of The Civil War, and the proper use of conjunctive adverbs. We should ban backpacks with more than three textbooks, any loose sheaves of paper and calculators with any kind of trigonometry functions. We shouldn’t give a lecture that is more than five minutes long or occasionally ask kids to just remember the assignment—as in just remember the conversation we had at the end of class.

Imagine the horror of so many when the first pencils with built in erasers tumbled off the assembly line. Mistakes could now be hidden with a simple flick of the wrist. How could teachers even begin to know what students did and did not know? Imagine a school allowing students to use textbooks to supplant the power of a teacher’s oration on any given subject matter?

Education is like a shark: if it does not continue to move forward, it dies. If education does not move in the direction of its prey, it ultimately weakens and dies. If we put myopic restraints on a teacher thing to put new and dynamic power into the hands of his or her students and forge a new and better way of learning, then education dies. No fish can ever be caught without stirring the waters, so we should embrace the messiness of learning as the tailings of a miner’s labor.

Which brings me back to this iPad of mine tapping away in the stillness of a late September night. It is my poets hoe, my pick axe, chisel and plane. It is doing what I need it to do at this given point in time. In a few minutes (I hope) it will be the final chapter in a good book. Tomorrow it may record my songs, film my video, craft my essay, fill my journal, create my quiz, model my discussion, post my assignment, paint my canvas, grade my homework—and when I don’t want it or need it, or feel if is useful, it simply disappears.

Back into my shed, my toolbox, or some dusty shelf…

The iPad is not a tool or a device or a thing. It is an enabler of possibility. Apps are not a panoply of evil undertakings; they are merely shovels and spades that let us dig deeper and faster and cut our corners as clean and square as Mike Mulligan and Mary Anne.

And I do not have a problem with that.

Don’t Do It

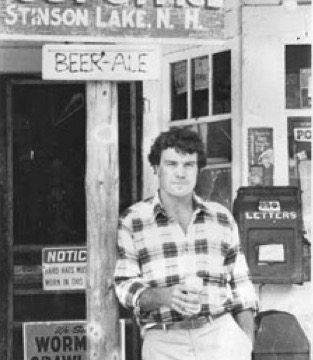

I was eighteen and designing a production line for making stepladders at Fitchburgh State College—the only college I could afford, and probably the only place that would have me. I remember thinking, ‘Man, this ain’t no life for me.’ I barely had a working idea of what life meant, but I was pretty sure it meant I didn’t have to do something without any meaning or purpose—and I certainly didn’t want to spend my life designing a better stepladder.’

But, what did I want to do? Did I have the courage to even make a change in my life? If I had read The Odyssey, I might have known what to do; I might have known that I was on a heroic journey and that my call to adventure was the churning confusion in my gut, and I might have known to look for a helper and an amulet to get me over the threshold—that no quest is real until you realize that you cannot go it alone.

My helper was my English professor. I can’t even recall her real name, but she was old and sweet, and so we called her Aunt Bee—and she was sweet enough to ask me to stay after class to meet with her one day early in the fall. (Although I was petrified she was going to have me expelled for charging five dollars to any kid in my dorm to write their English papers for them.)

Instead, she held a paper in her hand that I had written, and a paper in which I actually cared about what I wrote. The day before she had told us to take a walk through the city and then write about the walk. Most of my classmates stayed in the dorm, laughed about how naive Aunt Bee was, and wrote some insipid scrawls that they thought would qualify as an essay—or they tried to get me to write an essay for less than five dollars.

But I took the walk. I wandered through the poorest streets in Fitchburgh; I sat on front steps with little kids and old men; I sat with drunks and dreamers, and I wondered. I wondered if my walk was actually real, or if I was even real, and then wrote some story about a kid who couldn’t tell if he was awake or dreaming or even which state of mind he wanted to live in. Aunt Bee shook this paper in my face and said bluntly, “You shouldn’t be an industrial arts major. This [shaking the paper even closer to my face] is your gift!”

Never once had anyone told me I had a gift of any sort, except perhaps for whittling birds out of scraps of soft pine. I don’t think Aunt Bee knew how ready I was for a change—any change. I seemed to take her off guard when I responded, “Okay. So what do I do?”

“Leave this place,” she answered.

So I left.

Never had a decision been so easy and so hard at the same time. It was easy because I knew in my heart that Aunt Bee was right, but it was hard because my parents thought I was throwing my life away—and I was: I threw my old life away and charted a new course into a world of words and literature—a world that I really knew nothing about.

That decision in 1976 is the reason I am writing this to you today. It has been the proverbial long and winding road, but I have never been let down by a book or hobbled by anything I wrote, even though much of what I’ve written is pretty dumb and forgettable.

There was very little academia in my new journey. I learned to write by writing. I learned to write better by listening to what people thought and felt about my writing. I joined some writing workshops where each week each person would bring in some poem or story to share with a circle of other would be writers. I learned what worked in my writing and what didn’t work—at least to the small universe of my writer’s circle. I never thought I was a good writer, and so I was never really bothered by what people said. I just thought, ‘Cool. I guess I should change this….’

Even after a few workshops, I still never thought I was a writer, until I one day a friend introduced me to his friend by saying, “This is Fitz. He’s a writer.” I protested that I was not a writer, and my friend just said, “Then what the hell else are you?”

“I don’t know. An apple picker, I guess,” for at the time I was picking apples with a crew of Jamaicans in a New Hampshire orchard.

“At any rate, Fitz is a better writer than he is an apple picker. That much I’m sure,” my friend said, sealing the deal and sealing my fate—a fate which, by and large, has been good to me.

But be careful, for you, too, might become a writer; and once you become a writer, you can’t turn back; you can only turn away. Such is the power and allure of writing. If schools really knew what happens when a kid becomes a writer, they would ban the teaching of writing. It’s like giving a ten year old the keys to a bad-ass car; it’s like pointing across a canyon and screaming, “Jump!” It’s like opening the window and pointing in every direction and saying, “This is all you need to know and everything you’ll ever try to know.”

Writing is unfettered and audacious freedom.

Don’t do it.

Online Learning 1.0

Yikes! We teachers are being asked on the fly to be ready to shift to “online learning.” Schools might be—and some already are—closing their doors for as yet undefined periods of time. The Luddites amongst us are aghast while those geeky, trendy teachers are suddenly, and perhaps unwillingly, in vogue. Sheaves of paper need to be transformed into readily accessible online documents and new digital platforms need to ready—like right now—to engage and empower HUGE numbers of students and countless schools. Teachers, administrators, students and parents have to step to the plate and deliver, but this is a fastball across the corner of the plate, and it’s a small ball we have to hit. Though I don’t consider myself geeky, I have run a fair share of online classes. Hopefully, this mish-mash of thoughts might be helpful as we face this collective challenge.

Don’t be intimidated. You are probably already engaged in some variant of online learning. Anytime you post an assignment online you are making the first step. Attach a worksheet, a link, a video a quiz, a powerpoint—or any other kind of digitized or multi-media resources, and you are practically a pro. The first learning curve is to know what you can—and can’t—upload to and access from your school’s learning management system, aka LMS. This takes a bit of practice, discernment and organization. Every LMS is different, with different capabilities, so I can only say “embrace the beast” as well as you can. Leverage the strengths and work around the limitations of whatever platform you have in your hands. Even the most limited LMS can be augmented with other online platforms and apps: use shared docs to write essays and assignments, explore topics of interest in discussion forums, create class blogs, watch YouTube videos, make podcasts and utilize quiz-making software. You are only hindered by not trying. It’s a brave new world and, reluctant or not, you are its creator.

Look to the horizon and define (and sometimes limit) your expectations. Online classes require a different scope of focus. As the teacher, you are no longer the “Sage on the Stage.” You are the “Guide on the Side.” This transition can be difficult for educators used to being on stage in front of students leading an energizing classroom dynamic. Online teaching requires teachers to step to the side and be a subtle, guiding presence. As the teacher, you don’t, however, need to lose your commanding role as the leader of your class. Create a podcast, screencast or video that introduces the unit in a succinct (not too long) way that defines the focus, direction and expectations of what you hope to accomplish. Prepare them for battle, but don’t lead the charge.

Visualize your students’ experiences. By now, you have a pretty good idea of your student’s strengths and weaknesses; hence, your curriculum needs to paint both broad strokes that inspire the capable students, yet interspersed with enough precise detail to guide the more challenged students in a way that helps these students feel a sense of empowerment and defined purpose. Visualize these possibilities across the spectrum of your class. Juggle and adjust the details so that “everyone” has the power in their hands to be engaged and productive in their peculiar bents of genius in genuine ways.

Temper expectations with wise reality checks. Online assessments can become a black-hole of drudgery for you and a drag on the spirit of your students. Use shared docs for writing assignments and give appropriate and realistic feedback. This where you are the guide on the side. The temptation is always to give too much feedback, which is a sure-fire path to online burnout. I use a series of text shortcuts that highlight common errors as well as common phrases and comments of praise. By and large the kids are appreciative of short and personal comments, and they need a pat on the head as much as a kick in the behind.

Finally, don’t listen (or at least don’t give in) to those students who argue they can’t figure things out—that it is too complicated and too unfamiliar. At the same time, know your enemy and follow the KISS principle: keep it simple, stupid… Start with small steps and grow your online course in depth and breadth as your students become more adept as online students and you become more comfortable in this wild and worthwhile land of online learning. In the end, you will be amazed at what kids—and you—can do.

It’s what we—the grand and indefatigable we—have to do. It is not a choice.

I’m sitting here thinking of that old baseball movie where Kevin Costner builds a baseball field in some remote cornfield, and by the magic of the game itself, people begin to flock to that reinvigorated part of the earth. I’m wondering if the same magic can, could, or will happen here. Writing is as exciting as baseball–isn’t it?

Probably not, but it’s worth a shot.

Up until now, this site has been pretty much just a place for my students at The Fenn School to collect assignments, find the rubrics for writing and to engage in the discussion forums–but it has never really been open to or geared towards the general public.

My brother Tom, a successful business executive, once remarked that my approach to marketing is like a man opening a sushi restaurant with a big sign outside that say’s “Cold, Dead Fish for Sale.” And he is pretty close to the truth in that assessment, for my love for my music, writing and teaching has always been (and always will be) rooted in that one word–love. I do love what I do, and I “love” sharing what is quintessentially “me,” warts and all.

I added the “Welcome” essay to my site not to be self-deprecating, but simply to emphasize that I am not proclaiming this site to be anything more than it is–one man’s attempt to share who I am, what I do, and why I like doing what I do.

I have been a family prolific blogger for the past ten years, though my blogs have been spread around my private blogs I share with my students, a Typepad blog that I used for many years, and a blog I have kept intermittently on my music website JohnFitz.com. My hope is to now keep everything here. My larger hope is to host blogging communities directly on this site so that people who want to blog with a community of like-minded writers, musicians, poets and journalists (as in folks who simply want to share the art of journaling) can find a safe, supportive, and dynamic place to engage in the art and craft of what they like doing–and if that is something that interests you, I would be happy to have you as one of my first bloggers!

This is essentially “day one” for me, and it is pretty good to be here right now doing this. How it unfolds (and in some cases, I’m sure, folds) is the big unknown, but as Thoreau once wrote, “You only hit what you aim at, so aim high.” My highest aim is to realize the loftiness of my dreams–and to cling to those dreams however attainable or unattainable they may be.

So it begins…

Assessment is a terrifying word. I know my students fear it is just a softer term for the harshness of grading–an even more terrifying word, but if we do not assess everything we do, we become the proverbial bearers of repeated mistakes. There are few things that tick my students off more than to get a grade that seems pulled out thin air, riddled with inconsistencies, and is more punitive than enlightening or helpful—but grade we must. It is the Sysyphean chore and duty of every teacher—but does it have to be? Do we teachers have to be final arbiters of fate in this regard? Is there enough room and the grading house to allow the students in? Do our students have to always live like criminals turning themselves over to the authorities for every miscue and misdemeanor in their academic lives—and short of perfection, it seems to be their lot in life. But, if we do not let them in, and if we insist on being their judge and jury, we have squandered the greatest skill they need to master—to be able to to deconstruct their efforts with clear eyes, moral candor, and infinite hope of betterment. In short, let our teaching teach how to assess. Invite students in and let them share and dialogue and assess with us and with each other.

Research shows that we retain little of what we hear in the classroom. The odds increase somewhat (though not dramatically) when we also read what we are supposed to learn; however, learning increases dramatically when we need to present what we learn—and even more dramatically when asked to teach what we have learned. My own students know me as a bit of a pious bear when it comes to learning punctuation; however, as soon as I get on my podium and start talking about punctuation, the room is soon filled with what I call “grammar gas,” which always—as in always—works its way into the very souls of my captives until even the most focused, grade grubbing scholar fades from view and into their own solipsistic reveries—and sometimes simply slip into a hypnotic trance that actually mimics paying attention.

But (the proverbial “but”) when I free them to practice punctuation by watching my videos or laboring through interactive self-grading quizzes and worksheets, they will work endlessly until every single answer is right, and they will then strut around the classroom proud as peacocks to pronounce victory over a dreaded foe. The underlying magic in this approach is that they “see” what they need to do, and while they will never use the word “assess” they are actually living the experience of assessment. They have control of their respective destinies, and they intuitively know where and when they are screwing up and what they have to do to rectify the screw-ups. Putting these newfound skills into future writing pieces is another ballgame, but at least when that red pen circles the comma splice, they are the ones to take the blame, and they can look deeper into themselves for a solution instead of lamenting that I was grading them on something I barely taught!

During exam weeks, I am always amused by teachers who proclaim that no one in their class got higher than a C on his or her exam, as if it were solely the fault of the lazy students who did not prepare for the exam. I bite my tongue and never actually say that they had the whole year to teach what was on the exam. I shudder to think that my back surgeon needed to cram before boring into my spine with a drill! Knowledge needs to be organic. It needs to grow from a well-tended garden fertilized by a continual attention to what makes the fruits and flowers blossom and grow—but instead of a garden, too many students finish the year trying to make sense of a weed-patch of information until they hardly know the weeds from the crops. We move through our curriculums as if driven by a dark force that knows no other way. We teach. We assign. And we grade. And the vicious cycle leaves little room for true and effective mastery. We give what we think is helpful feedback and helpful criticism, but more often than not it is simply degrading commentary that diminishes more than it develops. None of us needs to be assessed more than we—students and teachers alike—as the creators of our works need to assess with skills and techniques that are helpful, hopeful, effective and practical in sustainable ways.

I am better at pontificating than problem solving, and I am loathe to have anyone come into my space and tell me what I should and should not do in my class. I am amazed every day by the sheer dedication I see in my colleagues in preparing their curriculums, grading great sheaves of papers, meeting with lost and wayward students, and easing the minds of over-anxious parents. But we are prey to our own inertia in all endeavors of life, and we need to rethink and retool the grading paradigm and channel our limited energies towards teaching students how to assess and how to move forward after assessing his or her work.

The bear that lurks in the corner of every classroom is the beast of time. No sooner has one task been completed when another rises from the ashes. The lesson planner becomes the tail that wags the dog, and to paraphrase Thoreau: we do not ride the railroad as much as the railroad rides upon us. Our destination is distant and our direction is fixed. The very notion of giving time to students to asses and reflect upon their work is a path fraught with peril and ambiguities, and so even the most well-intentioned and experienced educator is caught in the tangle of duty, obligation and tradition—and ultimately the energy for transformative change remains more dream than reality.

But you can’t jump a canyon in two jumps. We need to make the decision to change the way we grade, and our students need to learn to assess their own work in practical, pedagogically sound and sustainable ways—and we need to make the leap, or at least some of us have to make the jump, if only to show what is possible. All I know is that a good portion of my life is spent reading, marking up, and grading essays. In the crunch times of the year, this amounts to several hours at night when I should be watching NCIS with my kids. It’s crazy, as it seems we grade as if we are the ones being graded—and we are! These marked up essays make their ways into the critical banter in the hallways; they fall into the hands of parents who will dissect and parse our responses more than their children’s work, and we become the fodder of their disdainful gossip. In that sense, my way of grading works. I receive relatively few complaints and more than a share of praise for the efforts I put in, but I no longer think I am doing the right thing. I need to focus on teaching, not assuming a role as sole assessor and arbiter of right from wrong.

In my nostalgia for times gone by, I remember my days as a shop teacher when my most anxious moments at night was to remember to pick up ten 2×4’s at the lumberyard on the way to school—but maybe the approach in the woodshop is a better way. When working in the shop, I never grade their projects; I grade the process of the creation, which certainly levels the playing field. Most importantly, a shop student “knows” what the final product is supposed to look like. They work from drawings, plans, and blueprints; there is a logical and structure and sequence to the workflow, and they can palpably “see” when something is or has gone wrong. These bumps in the road are never a time for criticism—and the student willingly and eagerly seeks the help they need–but more of a time to “figure out” what is going wrong and how to fix it. The do not take the project home to work on the mistakes; they come to the next class ready to work through and overcome the setback. It is a lesson in teaching that can be built into any academic classroom.

The lightbulb for me is to do the heavy work in the classroom where a teacher has oversight of the process and approach—be it writing an essay, completing a lab report, compiling a presentation—or most anything! Homework needs to be what can realistically be completed at home and should be very specific to the needs of the work being done. With seven kids of my own, I have seen firsthand time and time again homework that requires to much processing time and not enough practice time. There is no reason that homework should be a source of massive anxiety, failure, and trepidation—it needs to be doable and calculated to take a certain amount of time, not a list which will take some 10 minutes and others thirty minutes, and it needs to be directly related to the work being done in the classroom. Now, when I assign thirty minutes of reading for homework, I make sure it is thirty minutes by providing audio that is thirty minutes long. If it is an essay or writing piece of some sort, I provide a detailed rubric (blueprint) for them to follow where I only expect a certain type of content not quality of content. If it something I want them to learn and practice by rote, I make sure it is measurable and limited using self-graded flashcard programs and interactive presentations and quizzes. If I grade any one piece of an assignment, it is the writing of a metacognition, which is a brief reflection on a students experience of the process. The refining of the content is always down in the shop…I mean, class.

I realize that to many teachers, my epiphany is no great thrust of genius, and it has been their common practice for years. It is a cornerstone of the flipped classroom, but it is certainly not an approach welcomed or practiced by the majority of teachers I know—some who are stubbornly clinging to the tried and true, some who sincerely disagree with me, and some who are too strapped for time to realistically rethink and retool what they do. The downside of my approach is the time and effort it takes to front-load the classwork and homework; the upside is a more empowered, confident and engaged student. Administrators would be wise to spend less time meeting with teachers and more time spent leading workshops and giving teachers the tools and time to develop and sustain this approach.

By doing the down and dirty work in the classroom, assessment becomes a natural and engaged action down with and through each student in an empowering and rarely punitive way. As teachers we need to see how and where a student struggle with our own eyes, mind and heart—and help them when needed, and we need to free them to figure it out when appropriate and, again, doable, which can only be done in the heady and invigorating dynamic of the classroom—the place where we as teachers have control and where out expectations can be carried out with a semblance of clarity and purpose. We cannot and never will be able to control the dynamic of the home environment. Never.

As always, I drone on. Sorry, but I get pumped just thinking of the possibilities of teaching that are more profound and enduring. Changing my ways (stubborn as I am) was a leap across a wide canyon, but the view from the other side is a pretty awesome view.

To assess is to progress. It is that simple.

The page you requested could not be found. Try refining your search, or use the navigation above to locate the post.

This is perhaps the biggest thunderstorm that I haven’t been in. The lightning is flashing and bolting to the ground, and the thunder is booming in every direction—though it is all five miles away. Here there is no wind or rain. The sky is bright directly overhead, but the tall pines on the far side of the field are backdropped in roiled, dark clouds.

Strange. There is a shift in the clouds. They are coming towards us now from the northeast….

I had to run from under the comfortable shelter under the awning of our RV and take some “shelter from the storm” as a huge gust of wind and pelting rain came at us from this strange direction. Just as suddenly, it shifted again and renewed its course to the southwest leaving me perplexed and dampened.

Writers often do the same thing with their writing. They build up a storm of unimagined intensity and create a looming confrontation between the opposing forces whom have been long at battle in their story line. Readers sense the impending conflict that will finally resolve the richly thickened plot; the wind whips, lightning flashes, thunder crashes and…

The storm takes a new direction—blows all hell and fury in another direction—and then returns to its insidious and relentless march to the sea (in New England, all thunderstorms march to the sea!) but the reader is no longer in the path of the storm; they are stranded like a desperate mariner on a now lonely shore watching the clouds boil away over the horizon. The writer, still caught up in his or her storm, assumes the reader is still with them anticipating the coming climax, but they are not. They’re more like me; they are left wondering why the storm took that irrational jog to the southeast, because that is the rational response to mystery—to ask why. There is no reason—aside from perhaps a schoolmasters admonitions—at require us to wade through the muck of tortured writing.

Most of us are rational and surprisingly intuitive, and a good writer needs to recognize and respect that reality. Good readers are like oft jilted lovers wary of another disappointing affair. They know when to put a book aside and find another writer, one who won’t let them down. They love the reward of a well-written story, an inspiring essay, or a compelling narrative; they love writers who consistently provide that reward, and they return to those writers over and again with their time, attention, and money.

A good writer is not in love with his or her own writing. They are in love with the process of writing well, regardless and because of their chosen genre! I will read and re-read Patrick O’Brien’s endless repertoire of naval sea novels, not because O’Brien’s novels are masterpieces of literature, but because he consistently provides a rewarding reading experience for “me” as someone who loves stories of naval battles! O’Brien found his niche, and he found his audience. It is an audience that he respected and worked tirelessly to please before passing away (sadly for his devoted audience eager for more novels) at a ripe old age. Though O’Brien will never be placed among the pantheon of “great” writers, what he aspired to do, he did well, and certainly well enough for me.

Thoreau once said, “Measure a man, not by what he is, but by what he aspires to be.” My readers are, by and large, writers who aspire to be better writers. In the greater scheme of things, I can only give you bits and pieces out of my own insights, experiences, and aspirations. I am only the proverbial finger pointing at the moon.

You will only reach the moon through your own labors.

~John Fitz

As with most poets trying to write a poem—in any style— the difficult part is getting started. In the complex swirl of life there might seem to be too many options, or not enough, and so a young poet may look like a confused archer in a chaotic battlefield. What a good poet realizes is that you can only shoot an arrow so far–and any attempt to shoot for something beyond his or her range is a recipe for failure.

But don’t worry; deep meaning is closer than you think.

Meaning can be found in the most common of situations: sitting around a table, laying in a field, or listening to a song. A poem does not have to be an epic battle. It is simply a way of seeing that our experiences of life can—and maybe should all be—meaningful. The reaching for a gallon of milk in the fridge can be a metaphor for love and care; the ringing of a phone can mean you are connected, or a simple wink of an eye can signify a mutual understanding. A poem is a package that is opened by the reader and appreciated with the same immediacy, even if the full use of the gift comes later—which it should if it is a good poem.

Start writing about something close at hand. You may well hot the target in the sweet spot.

Good writers borrow. Great writers steal…

And for these essays you are writing, steal from yourself.

All of you–both my 8th and 9th grades students–are smack dab in the middle of writing your essays. Everybody is under the gun timewise to finish these essays, so make your life easier: do not reinvent the wheel. You already made a bunch of wheels.

You guys in my 8th grade classes have reams of reflections about The Odyssey; likewise, my 9th grade class has already written quite a bit about Walden. Use what you have written. Steal your thoughts and recreate them in (perhaps) a more polished and structured form–a literary analysis paragraph!

I do it all the time. And I have yet to be caught and punished.

These essays should not require you to learn or study anything new. No writer writes well about anything he or she does not understand–even though they think they do–so just use some of the stuff you have already written and make them ready for the big time.

No joy for the writer. No joy for the reader. (oops…sorry Robert Frost.)

Few of you would bake a cake and not eat it. Most of you, especially if you are proud of your cake, would want to share your cake.

This is basically the idea behind your Odyssey Portfolio. Create something awesome. Share it.

A good protfolio is more than cut and paste. It is thoughful design. Rethinking. Redoing. Reimagining.

Anything can be made better.

And that is a good metaphor for life….

Here are couple of suggestions “if” you are interested.

Every museum has a main door, and that door is usually pretty interesting. I would consider using a separate page or even a blog as your welcome page. However, it should not be a blog with a bunch of posts, but rather a page that introduces and welcome readers/viewers to your Odyssey Portfolio. It may even be a place where you can put the video you have yet to create.

Consider making a page or pages for your writing pieces. It could be one page that a reader can scroll thorugh; it could be several different pages collated with analysis on one page, reflections on another, etc–or you could have a separate page for each writing piece.

The bottom line is that this is your portfolio, and it should refelct your taste, skills, and content.

We will have time to work on this in class on Friday, too.

So What’s Your Point?

The Uses and Abuses of Rhetoric

Knowing that you do not understand is a virtue; Not knowing that you do not understand is a defect.

—Lao Tzu

Nobody likes to be wrong, and for that matter, most of us “like” to be right. Few of us walk around writing, saying or thinking, “Boy, my opinions and views are certainly shallow, uninformed, and alarmingly trivial—but here is what I think….” We like to be assured that what we know and feel is valid and real and informed, for there is a serenity in knowing that we know—or that we have thoughtfully reached a level of knowingness that is somewhere near to certainty. I admit that a certain jealousy sweeps over me when I hear or read someone say exactly what I already think and feel (and though I knew) but I just never found the words or the way to say it with that much eloquence and clarity. Or I am at a party and two prodigious minds are arguing a topic, and I find myself swinging dizzily from one side to the other: “He’s right. No, she’s right. But he made a good point. Now her’s is better.” Worse is when I decide to butt in to the conversation with my limited skills and sketchy half-ass information, and I am forced to slink away with my tail between my legs like a proud, yet sheepish, cur. In each instance I have been victimized by a majestic and compelling use of rhetorical language—which is simply effective and persuasive speaking or writing. But don’t fear. Becoming a more adept rhetorical speaker and writer is a skill that can be learned and practiced in every facet of our academic, social, and intellectual interactions.

The first skill is to stop. Think. Think some more. Then speak. Lao Tzu had it right almost three thousand years ago when he wrote the short poem posted above this essay. He was no doubt annoyed by people who were obsessed with being right, but who were not equally obsessed with knowing what they needed to know before opening their big mouths or wetting ink to papyrus! The wisest and most enduring advice then is to stay the heck out of conversations you have no right or aptitude to be in. Sadly, Lao Tzu’s wisdom is lost on most people, for our lives are full of moments where we are carried away by the ephemeral sound of our own voices and not by the content and wisdom of our arguments. We only need to read or hear the endless screed of Facebook postings, political rantings, and absurd comments that so fill our everyday lives to know that we live in opinion-full, yet shallow, times. I am just as guilty as any of you. Regrettably, it is often impossible to undo what we say or write or post. The only practical (and wise) thing we can do is to start fresh and choose our arguments more carefully, think more deeply, and know when, where, and how to say or write what we want to say or write. Only then will our rhetoric rise to the level of the sublime. Hopefully, this set of criteria for speech giving will not banish us collectively to a vow of silence, for there is much each of us do know, perhaps more than any other person on the planet!

The second skill is to know that a gaggle of thoughts and opinions cannot be simply dumped on the page or on the person like an elaborate jigsaw puzzle. We need to complete the picture for our listeners and readers; moreover, we need to let our listeners and readers feel like a part of the building process for without a sympathetic audience our words are but emptiness in a vacuum, and our rhetoric will be a self-aggrandizing show-boating of our superior and subtle thoughts, and we will not convince anybody of anything. A good rhetorician understands his or her audience as fully as the subject matter, and they are willing and happy to meet that audience on a common field of play with a common set of rules for the game at hand. I worked for many years as a boatbuilding wood-shop teacher, and my mantra for building a simple boat has always been the old maxim that “form follows function.” It is much the same with rhetoric: the ways in which we build our arguments and state our cases need to be crafted with the same adherence to sound and effective principles of construction as a craftsman building his or her boat. No doubt there are new and radical boats launched every day, but every one of them must float, and they must move through the water in some semblance of the way the builder hopes they do, or else it is essentially a failure. Interesting, perhaps—but still a failure. Some people have mastered the art and craft of rhetoric through experience, reading, practice, common sense and an uncommon intuition; most of the rest of us are best served by listening, watching, reading, parsing, and perfecting the time-worn and time-tested formulas and spontaneous performances of whomever we feel is simply awesome at drawing sap from a telephone pole, a meal from a loaf of bread, or, simply, sense from sound.

The final skill (which I need to practice right now) is discerning the limits of what you know well enough to speak or write sensibly about, so this is where I leave you off because I am pretty sure that I have reached the limit of my erudition on rhetoric—though not my interest in the subject. I need to be content at this point to be, as Buddha once said, the finger pointing at the moon. If you really want to master the art of rhetoric—if truth is mightier than the sword of your opinions—you’ll figure it out. The obvious starting point is to read Aristotle’s seminal work, Rhetoric, or even just the history of the discussions surrounding rhetoric and its uses and abuses in ancient Greece to the present times. There are reams of discussions and treatises on rhetoric in print and widely available on the internet. Reading Aristotle, who is way more wordy than Lao Tzu, is a sensible place to begin; but, at the very least (and before your next argument) remember what Mark Twain said: “If you don’t lie, you’ll never have to remember anything.”

Years ago I wrote in my journal that my goal in life was to be small, be simple, be wise, be happy, and above all be ready. I cannot honestly say that I have achieved all of these goals, but these are still the “ideals” I strive to live in my life. These are my necessities—and as necessities they are by nature, finite, as opposed to my “wants,” which are seemingly endless…. Our essential question for the year is “What are the necessities of a fruitful and rewarding life?”

My necessities surely are not the same as yours. Perhaps you have never stopped to consider what you consider the necessities of your own life. But you should, and it is my earnest hope that you will. The great writer and philosopher James Henry once wrote that “thoughts are only made real when put into words.” My goal for the year is to help you make real what is in your head and heart. In essence: to begin to discover your true and most perfect self, and to build a foundation under your dreams upon which you can build a good and lasting life. I cannot tell you what this will look like, but I can point you in the right direction–or at least, a direction. The rest is up to you. Your summer reading books,

Your summer reading books, Into the Wild, and The Outermost House describe the attempts by Chris McCandless and Henry Beston to seek profoundly rewarding lives by removing themselves from “society” and attempting to live simply and wisely and as close to nature as possible. Chris, of course, met a calamitous end in the wilds of the Yukon. Beston thrived in a less harsh (though in many ways no less wild) year spent in a small cabin on the outer beaches of a Cape Cod that at the time was a pretty much untamed and scarcely visited stretch of lonely sand and surf. McCandless’s story was told for him by another writer, Jonathan Krakauer, who found Mccandless’s adventure to be newsworthy and worth telling. Beston told his own story in descriptive prose that is widely considered some of the best writing in the English language—though I am sure some of you will disagree with that assertion! For many of you, The Outermost House might have seemed like the most boring book you were ever forced to read. No harm intended. I get that, and I get why you might feel that way. Nothing much really happens: he walks on the beach, describes birds and waves and winds and storms with excruciating detail, but there is no obvious crisis, no looming antagonist to put him in peril. Putting the two books side by side is almost unfair. In

In Into the Wild at least there is true adventure—an adventure which killed Chris in a slow, lonely and cruel way. The Outermost House, on the other hand, reads more like an intellectual and overly detailed diary shared with kind and forgiving friends. So why is it that I am perfectly satisfied to read Into the Wild once and be done with it, yet I can pick up The Outermost House year after year and reread it with ineffable joy and satisfaction? Perhaps it is because Beston’s words grow with me as I grow (and yes, I am still growing!). Perhaps it is because Beston loved and studied the wild loneliness he experienced, while McCandless seemed to continually fight with an unforgiving and harsh nature (and his own harsh nature) in every step of his fateful journey. Perhaps I remember a side of me that was once like Chris McCandless—a darker side of my life best forgotten. More than likely, I return to Beston because he continually gives back to me. I feel wiser and more complete and more human every time I read his words. His words make me want to bring my life back to the wheel and polish it to a more perfect edge, an edge that can cleave apart the tangle of weeds I might be lost in. His words affirm my own desire to live simply and deeply. Mr. Farely and I did not assign these books in an inconsiderate way. In fact, the decision was quite considered. Our hope is that we can start a new conversation with all of you and each of you, and that you can start a conversation with yourself–a conversation that will fill our coming year together. So ask yourself: Why do you want what you want? What do you really need? Maybe there is power in simplicity….

More than likely, I return to Beston because he continually gives back to me. I feel wiser and more complete and more human every time I read his words. His words make me want to bring my life back to the wheel and polish it to a more perfect edge, an edge that can cleave apart the tangle of weeds I might be lost in. His words affirm my own desire to live simply and deeply. Mr. Farely and I did not assign these books in an inconsiderate way. In fact, the decision was quite considered. Our hope is that we can start a new conversation with all of you and each of you, and that you can start a conversation with yourself–a conversation that will fill our coming year together. So ask yourself: Why do you want what you want? What do you really need? Maybe there is power in simplicity….

Perhaps it is because Beston loved and studied the wild loneliness he experienced, while McCandless seemed to continually fight with an unforgiving and harsh nature (and his own harsh nature) in every step of his fateful journey. Perhaps I remember a side of me that was once like Chris McCandless—a darker side of my life best forgotten. More than likely, I return to Beston because he continually gives back to me. I feel wiser and more complete and more human every time I read his words. His words make me want to bring my life back to the wheel and polish it to a more perfect edge, an edge that can cleave apart the tangle of weeds I might be lost in. His words affirm my own desire to live simply and deeply. Mr. Farely and I did not assign these books in an inconsiderate way. In fact, the decision was quite considered. Our hope is that we can start a new conversation with all of you and each of you, and that you can start a conversation with yourself–a conversation that will fill our coming year together.

So ask yourself: Why do you want what you want? What do you really need? Maybe there is power in simplicity….

Recent Comments