by Fitz | Jun 23, 2020 | Essays, The Crafted Word Blog, Workshops

Write what you know.

~Mark Twain

I don’t always practice what I preach, especially when it comes to the simple, unaffected, and ordinary “journal entry.” Much of my reticence towards the casual journal entry is the public nature of posting our journal writing as blogs that are more or less “open” to the public. It is hard for me as a teacher of writing to post an entry that I know is trivial, mundane, and perhaps of no interest to my readers—but that is precisely what I need to do if I am to model the full spectrum of the writing process. Keeping a journal is more than a search for lofty thoughts amidst the detritus of the day; it is a practice that keeps our wits and writing skills honed for a coming feast by rambling through the meat of the day and drifting and sailing to whatever port is nearest to my pen. Writing is always an odyssey, and so I have to let my mind go and journey (journal) where it will.

Good words are built our of ordinary thoughts. At the very least, a journal, filled with the scraps and pieces of our daily lives, will outlive our own lives and serve as both beacon and reminder to future generations. Once, in my days as a junkman, I cleaned out an old barn in Maynard after the elderly widower—a man I only remember now as Bob—had died. Scrounging through the Bob’s boxes for anything of value, I came across a series of leather bound journals dating back to the 1930’s. I found a journal marked 1941, so I looked up the date of the Pearl Harbor attack, eager for insight on the profound effect that day must have had on the common man of his or her time. I turned through page after page of impeccable script and learned that Bob and his family went to church in the morning, during which they sang certain hymns (hymns that I can’t remember now—but he did.) Afterwards, they drove to Stow for dinner with his extended family. He wrote about the meal, the weather, the condition of the roads, and, in two brief lines at the close of his entry: “The Japs attacked Pearl Harbor today. I trust President Roosevelt will know what to do.” And that was it.

At first glance, I saw a xenophobic racist putting blind trust in infallible rulers. I couldn’t reconcile it with the kind and gentle old man, and best friend to my best friend’s father, who had recently passed away. I didn’t see it as a window into another time and another mindset. In the arrogance of my youthful pride, I couldn’t appreciate the elegiac beauty of his day—a whole day devoted to faith and the full circle of family. It wasn’t until years later when I sat on the bench by the World War Two Memorial in downtown Maynard and scrolled through the scores of boys and men from this one small mill town killed in battle that I realized the full extent of my myopia. I should have sat in his barn for days and read every word from his journals and then, maybe, I could have seen the evolution of a person through the fullness of time through the clarity of still waters.

Maybe Bob’s youthful ramblings, tempered by the death of so many of his townsmen, could have somehow transformed into the pearls of laconic wisdom that old age should bring—pearls that would fetch a heady price in the market of the modern mind. The greatest tragedy is that we’ll never know. I offered the journals to his son, but he was content to have me throw the whole lot into the back of my Chevy pickup and pay me fifty dollars for the load I scattered into the fires of the Concord dump. The irony of tossing those journals away not more than 150 yards from the site of Thoreau’s cabin on Walden Pond remained lost on me for many years, even as I trudged dutifully to the Concord library to scour through the massive tomes of Thoreau’s own journals. The old man had done exactly what Thoreau believed was required first of any man or woman when he admonished all would be writers:

“I, on my side, require of every writer, first or last, a simple and sincere account of his own life, and not merely what he has heard of other men’s lives ~Henry David Thoreau, Walden

A further irony is that my own journals from my years between eighteen and twenty five years old, which filled a good-sized cardboard box, were also inadvertently tossed into the same dump by a roommate intent on purging all the junk we were accumulating in our Williams Road farmhouse. The Concord dump is now a series of perfectly sculptured hills slowly regaining the shape and character of the woods that Thoreau tramped and stumbled through 150 years ago. It is a noble idea funded by the well-intentioned, but a nobler action would be to dig through the mold and dirt of time and truly find what the past has to offer us, buried almost irretrievably as it is.

Poetry is what is left unsaid. The stolid words of brevity simply point us in a direction only the brave will wander, but through the daily words of an old Italian farmer, I found a new kind of poetry. Pine Tree farm, butted against the rail line on the far side of Walden and owned by the Ammendolia’s, was one of the last of the Italian family farms that used to be scattered in every corner of Concord. Tony Ammendolia was the patriarch who somehow kept the dream alive, even as farm after farm succumbed to the teeming aorta of suburbia. It was there where I worked on school breaks and on summer weekends, picking corn at 4:00 AM before the heat of the day and hoeing seemingly infinite rows of tomatoes, beans, pumpkins, and eggplants in the long, hot afternoons where success and failure crisscrossed and intersected in a struggle to just get by. My Goddaughters were raised there, and their parents, my good friends Deb and Jack, still keep a few acres going to this day. Tony died two years ago after defying for many years the cancer he fought with the same stubbornness that he did the vicissitudes of nature in the cycle of droughts and floods and insects he faced at every turn during his days as a farmer.

Every night for over sixty years Tony would sit at his desk after dinner and write in his journal. Tony knew I was a writer and would kiddingly tease me that he was a writer too, but in a good-natured poke at my transient approach to life, he was also a farmer. I was at Jack and Debs recently for dinner and asked about Tony’s journals. Jack perked up as the proud inheritor of this family treasure and immediately found me one of the many small notebooks that Tony kept. I opened it and felt the tears well in my eyes, for it read like a type of poetry I had never read before. Tony never meandered from the scope of his own life, but his words spelled out a conviction that celebrated both the common fragility and majesty of life with sentences both sparse and foreboding: “Potato beetles got the eggplants on Bedford Street. We will not sell eggplant this year.” “Three days of rain. Lucky, as the irrigation pumps needs a new valve.” Each entry is a sublime excising out of the ordinary: the sky, the temperature, what was done, what had to be left undone, how much seed, what was selling and what was not selling—but never a mention of the money made or not made. There is never a mention of personal angst or frustration for over sixty continuous years. Those details were best left to imagination and speculation. Some, myself especially, have to call it poetry.

Our own journals need the same attention that Bob and Tony put into their daily records so that our journals can also chart the common unfolding of our lives. As writers and sojourners in life it is our call and duty to map the expanse of our existence. We don’t need to lay our souls bare for all to see and gossip about, but we should find a place to keep a daily journal. Whether it is written in leather bound journals, spiral notepads, or saved as private or public drafts in your blog doesn’t matter, but just a few short lines each day will serve to spark your memory in a later age—and memories wizened in the vat of a thoughtful life will always produce a finer wine. Journaling is a word that has been antiquated before its time. Though fewer and fewer of us take the time to sit with pen and paper, there is still a time and a place for the spirit of journaling to continue.

Make the time to map your own quest. A friend asked me yesterday why I didn’t have a GPS in my truck. He simply shook his head when I answered, “First, I have to remember where I’ve been.” Today’s technologies offer us possibilities unimagined to our literary forbears. Our daily journals can hold both pristine images of our lives via photos, video clips, and music, and most importantly, words. The web allows us to scour the world for like-minded souls that share our particular interests with whom we can share our passions on sites like Facebook, blogs, or personal web sites.

My only issue with much of what is out there on these sites is their self-exploitive and indulgent banality. Bob and Tony’s journals seemed permeated with an almost religious devotion as they chronicled the recitations of their days in rhythm with the pattern of their everyday lives, while on the other side, many Facebook sites I have visited have a tiresome and sycophantic obsession with the painstakingly mundane and profligate side of that persons supposed interests and lifestyle. It is hard—and sometimes impossible—to wrest any kind of context out of the content. Nothing, except a prurient curiosity, keeps me interested—and that is no road to enlightenment for either side of the equation. On some few sites there are links to blogs and other artistic websites where a deeper and more invested side of that person comes through. For them, their Facebook page is simply an adjunct to their life—a social gathering place to rest and draw water with friends and community. There is nothing wrong with that, but it should never be the destination of your journey, and if you can’t see life as a journey—an odyssey of existence—then you simply can’t see.

I guess the word I am looking for is devotion. None of our lives are more complicated than Bob or Tony’s lives. All they did that is different is make time to look closely at what was important to them in the daily unfolding of each of their lives.

Take the time.

Remember where you’ve been.

by Fitz | Jun 22, 2020 | Essays, The Crafted Word Blog, Workshops

Explore, Assess, Reflect & Rethink

How to move on to a better tomorrow…

For most of us teachers, our first crash course in remote learning is done, and the wise work now is to separate the wheat from the chaff and truly assess what works and what can be cast aside as detritus from a noble effort. I have always required my students to write a “metacognition” after each assignment as a way to explore, assess, reflect & rethink their unique experience of a common assignments and assessments. These dreary, one more thing they have to do drudgeries evolve over the course of the year from stuttering incantations of frustration into honest and compelling reflective exercises that reflect the “meta” of “cognition” in rich and nuanced narrative voices.

As educators, we would be wise to do the same while the bloom still clings to the vine and the muddy dew is still fresh on our hands. No doubt, it seems that remote learning is not going away. The likelihood of the coronavirus magically slipping into mere memory diminishes with each passing week, so yes, we need to prepare, but no, we do not need to make rushed and hurried decisions and leaping into professional development until we are sure what needs to be and can be developed over the course of the summer and before the looming reality of “The Fall Semester.” My cantankerous and curmudgeonly self already fears the slew of opportunities hell-bent on doing me good. I am an old and hardened soldier leery of being pushed into the mud before I dance to the old songs I know.

It would be handy and convenient to simply accept that “We’ll listen to the experts,” but who is to say with clarity who these experts are? As a teacher, I would answer, “We are! Each and every damned one of us!” We have all had our flashes of brilliance, and we have all had, more than likely, our share of fizzled duds, but we are, by and large willing to transform what we know into what we need to do. To administrators I say, “Give us the tools and let us build our own castles on the foundation of our unique school communities.” If we are unwilling or incapable, then by all means dictate and proscribe what you will in ladled dollops of wisdom and stubborn persistence. To students I say, “Be the kid who figures it out; not the lazy slouch who figures a way out. This is your new and inescapable garden in which to wither or bloom.” To parents and guardians I say, “Embrace the beast and do your best to tame the wild urges to let it run wild. You are no less a part of your child’s education than any teacher or school. You are the model of your child’s future, so be strong, wise and demanding.”

Oh, to be a fly on the wall to hear the chats of our students, the mumbles of our colleagues, the scrambling of administrators trying to put this whole ecosystem together, and the exasperations of our parents as education morphed from walking in to logging on; from engaging in the sensate repartee of the classroom and the bustling of a school community, and shifting on the fly to the hard screen of Zooms and uploads, halting connections and distracted, unkempt students still deep in the torpor of sleep. Even as summer begins, most of us are tired and weary. We live in a world that is cobbled together with loose stones and thin mortar. It is easy to lose faith and fear all that lies ahead. For the past three months, school was not what it was, and in many cases, not what it should be, yet, somehow much of it worked, and often to an astonishing degree. On successive days we have all been the hero and then the fool. In spite of any and all frustrations, our own experiences must now shape a new paradigm that can–and must–work.

Our lives and our experiences must become the parable that guides our future. We should start by imagining or reliving those babbling and disjointed conversations of what was good and what was bad, who was right and who was wrong, what worked and what didn’t work. We need to focus on our individual successes as teachers, our efforts as students, our thoughtfulness as administrators, our undeniable rights and roles as parents, and we must explore, assess, reflect and rethink–and separate the wheat from the chaff. That cannot begin until there is and acceptance that education is a three-legged stool; that there needs to be true and searching reflection on the parts of educators, students–and parents, for we all play an equal role in the dynamic that determines the success or failure of the second iteration of Remote Learning 2.0.

It is a new day and time for new ideas. The bell tolls for you…

And us.

by Fitz | Jun 22, 2020 | Essays, The Crafted Word Blog, Workshops

Words matter. Words carefully crafted and artfully expressed matter infinitely more. There is something compelling in a turn of phrase well-timed, arresting image juxtaposed on arresting images; broad ideas distilled into clear, lucid singular thought. For the writer, it is empowering to know that his or her words have the capacity to engage and effect change, to alter perceptions and persuade a living audience–not merely to share stale thoughts and shallow opinions, but to articulate what needs to be said in a wall of words that will stand the test of time and speak powerfully to the present generation and inspire succeeding generations.

Words… these damn words clabbered together–they are our gift to eternity. Learn how to use words; learn how to craft them together, and learn how to live the life of a writer. If you want to be a writer, live the life of a writer. It really is that simple: if you want to be a writer, live like a writer. Read. Write. Create. Share. Don’t push a loaded cart up a slaggy hill. Let the engine pulls the train. Learn the craft and the art will follow. You don’t have to be the drunk stumbling down a dark road howling inanities in the night, but even that is better than not howling at all. Howling is the birth before the epiphany, but after the primal howling in the dark, after the grimacing at fate, give the time and the space needed to till, plant and sow a more perfect garden with the seeds of your original cowlings. Nurture that garden as a farmer of words and bring your fruit to the market. It may well that your basket comes home more full than sold, but you are now the farmer of your mind and soul and heart and being, not the hungry pauper trying to fill a crumbling sack, scrounging for cheap seconds at before the shutters of commerce are drawn.

“A stitch in time saves nine,” or so the old adage goes, because a writer is a weaver of tapestries. Everything we write is a new mosaic of woven cloth–an original expression of who, what, when, where and why we are at any given point in our fleeting existence. We are not born weavers, but all of us have some rudimentary concept of a needle pulling thread. We understand the process. Every time we speak, we are stitching something together, weaving together words, struggling to hold together a wretched pattern of thoughts into a coherent conversation worth having; however, our opinions too soon fray and are soon too tattered to wear and are equally too soon forgotten.

But not so for the writer. The true writer goes back to that tattered, convoluted and forgettable conversation–an interplay of words sown, no doubt, with strong seed on thin topsoil where even the heartiest of intent withers on a dry vine. True writer do not give up on possibility; they go back and rebuild those same words and thoughts into a more perfect and palpable tapestry–a living and breathing garden of mind-swollen and succulent fruits worth bringing to market. What starts as a rambling in a journal evolves into something that resembles clarity and, ultimately, something worth sharing. It does not, however, just happen because we want it to happen. It happens because we make it happen. It happens because we learn to weave and stitch, and we learn to till and plant and cull the good from the bad.

The recipe for success is as old as time: learn, practice and persist. As a teacher of writing and as a writer, I am simply one of many pointing my finger at the moon. Your journey is uniquely your own. If you are not thirsty, then every well is the same. But if you are thirsty, go to the deepest, purest well and drink deeply until you are filled or have sucked it dry. To live the life of a writer is to live with an unquenchable thirst for that purity of thought etched upon a page of time. Your journey to the moon itself is distant and dangerous, and even the moon has only a reflected light, but everything you write serve as waypoints to map your journey–these linear dots arcing across the universe prove you have escaped the lure of gravity and the myopic confines of the muddy orb of earth.

That journey proves proves you are a writer–that you have not chosen the easy path with words, but the path of the explorer, the weaver and the farmer… and that is always worth it in the end.

by Fitz | Jun 16, 2020 | Essays, The Crafted Word Blog, Workshops

The Rules of Punctuation

If you don’t use it, you lose it…

~Fitz

What do you really need to learn? What teaching and what practice will help you learn what you “really need to learn” in a way that will somehow stay with you and be useful and necessary to your life.

Most all of you are pretty lucky I did not “grade” your most recent essay harshly for missing and misused punctuation, though I probably should have graded those few students who were in my class more harshly. It’s only fair. I practically beat them over the head last year with comma rules, hyphens, long dashes and semi-colons, brackets and the weird three-dot thingy. If they have forgotten, I blame myself. What kind of English teacher can’t teach what is basic and critical to good writing?

Me, I guess…

I think when the average teenager hears the word “rules,” he or she immediately starts building a wall to keep that rule out of mind and out of sight. It’s too bad because rules are what keep us going, and if we don’t keep going, the fun ends. Imagine Fortnite if someone hacked the system and no one could be blotted off the screen? Imagine the millions of whining men and boys across the world having hissy fits and swearing into headphone mics when their perfectly placed snipe had no effect on the clueless soldier hopping across the screen?

Imagine soccer without goals. Imagine bread without flour. Imagine the earth without a sky. Imagine words could be any jumble of letters. Songs could be any arrangement of notes–parents could choose their kids and kids choose their parents…

Get where I am going?

And what does this have to do with punctuation?

Punctuation simply connects “thoughts” (clauses) and “fragments of thoughts” (phrases) together in a way that mimics and reproduces the effect of an ordinary conversation–or a profound rendering of poetry, or a stupid and insipid movie you wasted ten dollars going to see on an otherwise perfectly fine Friday night. As far as the written word goes, the rules of punctuation follow the laws of physics. Without them, nothing holds together.

Where does this leave you, coming with trepidation to the assignment page?

It leaves you in the crosshairs of a cold and calculating teacher measuring the distance between himself and his unsuspecting students–measuring their capacity for genius; discerning what exactly will help them learn, remember, practice and use “The Rules of Punctuation.”

You will find that The Rules of Punctuation are a beast you cannot slay; you cannot avoid, and you cannot ignore.

Your only option is to Embrace the Beast, wrestle it down and hold it down until it is tame, and when it is tamed, morphed into a friend and ally, it will follow you around the rest of your life and will always be faithful to you, protect you and strengthen you.

And maybe then you can pen a letter of thanks to me, long since retired and living off the memories of students who actually gave a damn and made something with their lives.

by Fitz | Jun 14, 2020 | Essays, The Crafted Word Blog, Workshops

So much depends

on the red wheelbarrow

glazed with rain water

beside the white chickens.

-William Carlos Williams

It was funto be swimming and clambering around with my kids yesterday in a remote stream in the Berkshires and thinking: “This would be a cool experience to blog about!” People ask me sometimes if encouraging people to get on the computer is a “good thing.” As with anything in life, it is only a bad thing when it is used un-wisely or at the expense of living your life to the fullest. As I write this on my back porch, Charlie is swinging on a rope swing, EJ is collecting ants for his ant farm while Tommy investigates and shouts with joy at every caterpillar he can find. I am eager to pack up the bus and head to the Cape and get my old sailboat in the water, so I can spend longs days (and some nights) cruising around Pleasant Bay and Vineyard Sound.

After years of teaching writing, I can say with confidence that personal narrative writing is the number one BEST way to improve the overall quality of your writing. You have to have experience before you can recreate that experience—a lesson often lost in classrooms.

Personal Narratives are the stories of our lives. By habitually practicing the art of storytelling through personal narratives we practice the basic craft of the Short Story and the Essay. By telling the stories of our lives we follow the main rule of all writing—write about what you know! I could write all day about the joy of bungee jumping, and I still couldn’t convince a toad that I knew what I was talking about. But, if I wrote about the day I watched people bungee jumping off a bridge, then I could probably get that toad to publish the story for me. I could be the protagonist, and my best friend forcing me to try could be the antagonist; fear of jumping into the unknown could be the conflict; standing up to my friend could be the climax; falling out of a tree when I was young could be my supporting facts; facing and trying to overcome my fears could become the theme of my essay/story. When a reader relates to your theme, they are able to recreate your story in their own imaginations. It might force them to think about their own fears, and in doing so, your story creates a powerful transformation in their lives.

Every day and every experience is a possible personal narrative. If that experience means anything to you, it will mean the same thing to someone else because we are all tied together by our “common humanity;” we share the same emotional connections, but how we experience those emotions is infinite and infinitely varied—and that is why our libraries and bookshelves are filled, and that is why we all keep returning to the power and creative magic of literature. Think of everything you write as true literature.

As a way to begin, don’t get bogged down by form and structure, but do ask yourself why you are writing about that experience, and do ask yourself “How am I telling my story?”.

Here are ten ideas I keep in my head when writing a personal narrative. These ideas also work for any type of short story fictional or real:

Put a man in a tree. Throw stones at him. Get him down: That is to say, whenever we write a personal narrative or a short story we need to create the scene, show the conflict, and then show how that conflict works itself out. A narrative without any form of conflict is like an egg without a yolk: it is simply (and sadly) not a good story.

Make sure your reader has an idea of where you are taking him or her “early” in the story. Nobody likes to get in a car blind-folded with a stranger and have no idea where he or she is taking you. You will jump out of the car at the first chance you get! You don’t need or want to be specific right away about where you are going with your story, but you certainly want your reader to feel like it is going to be an interesting ride. A simple strategy is to make sure that somewhere (preferably at the end) of your first paragraph there is some kid of guiding statement or foreshadowing technique that assures your reader that your story is going to be worth ride.

Use specific images and actions to tell your story: Always remember that your reader is not “in your mind.” They can’t see what is in your head until you “show” them. Use nouns and verbs to create those images and actions. Your readers can put together nouns and verbs without much difficulty. Use adjectives and adverbs only as a way to help your reader—not distract them. The “red wheelbarrow, glazed with rain water beside the white chickens” is a great way to “paint a scene.” If William Carlos Williams wrote the same line as, “the chickens are next to the wet wheelbarrow,” then his poem would probably have died after a short and unnoticed life.

Well chosen dialogue makes everything you write come alive: Words spoken by people who were with you act like supporting facts in an essay. They are proof that what you say is true, and serve to engage another part of your reader’s senses. Remember to always lead into a quote by setting the scene; don’t just drop dialogue int a writing piece with no context to “hear” that dialogue spoken.

Punctuate as well as you can: For the most part, punctuation is all about the comma—everything else flows from understanding of when and where the comma works best. In future posts, I will deal with commas and other punctuation in more detail. For right now, just be aware that punctuation (a relatively recent part of the creative process) simply helps your reader experience what you want them to experience in the way that “you experienced that event.

Use paragraphs to lead your reader through your story: Contrary to what we are often taught, there is no minimum or maximum “length” for a paragraph. In a short piece, short paragraphs work fine. Long paragraphs work well in longer pieces. As a suggestion (not a rule) have the first part of your paragraph indicate the direction or idea you are going to write about. (I call those sentences “guiding themes.”) If when writing or editing you find yourself “off of the idea,” then simply start a new paragraph.

Try to end your story by leaving your readers thinking, wondering, wowing, squirming or relieved: Just don’t leave them hanging, and don’t end so abruptly that they feel cheated out of well-told story. If your story is well told, the ride is always worth it.

Proofread before you publish: Spell-check, fix, change, delete, move, and do whatever you need to do to be happy with what you’ve finished (or thought you finished:). It is only easy if you try.

by Fitz | Jun 12, 2020 | Essays, The Crafted Word Blog, Workshops

Know Thyself… Explore, Assess, Reflect & Rethink

If we don’t learn from what we do, we learn little of real value. If we don’t make the time to explore, reflect and rethink our ways of doing things, we will never grow, evolve and reach our greatest potential or tap into the possibilities in our lives. Writing metacognition’s is our way to explore our experiences as students and teachers, and then to honestly assess our strengths and weaknesses, to willfully and wisely reflect on what we did—and did not—do, and to rethink how to move forward in a positive and more enlightened way towards a better and more applicable and capable future.

There are many sides to every experience, so when I ask you to “explore” an experience and write a metacognition, I am not looking for a simple summary of what you did. I expect you to write like you are walking the rocky and jumbled coastline of what you just went through. Recount and relive your experience in a stream of deliberate, dreamlike consciousness. This recounting and reliving can be as scrambled and unkempt as your emotions and memories; there is no “Fitz Rubric” to follow; there are no specific“details” to the assignment—there is only you and your own heart that you can follow with your own iconoclastic bent, will and resolve. You do not have to worry about being understood by your reader. You are only trying to understand and know yourself.

When you assess, there is no way around the need for a bit of cold and reptilian critique. Looking with clear eyes upon yourself is a hell of a hard task, but it is part and parcel of a thinking person’s package. Sure enough, the assignment might be so flawed as to be undoable, but that is, I hope, fairly rare. More likely the great flaw (or the great promise) starts with you, your attitude, and your way of tackling the work. And it ends with you. Pull out a scale and a measuring tape and tally what you produced; weigh it against the scale of time you stole from your life to complete the work, and ask yourself: do you feel like saying, “Check it out,” or do you feel like sighing, “Chuck it out.” To assess is to figure that out.

Once “that” is figured out, your head should kick into full reflection mode. A reflection scours the deeper trenches for whatever insights can be culled from the briny mud of experience. Pull these thoughts and splay them on the deck as they come, for they are all gifts from the sea of the mind, and their true value can be discerned later and kept or cast as wanted or needed. There is no such thing as unwanted catch in a reflection.

If you are unwilling to rethink your actions you are, to use an old adage, condemned to repeat that action. By rethinking approaches you can retool the machine of your being, and in that sense you are continually reborn as a better you. You make sense of yourself and are now clad in a stronger armor with a shield,pike and sword better suited to turn the tide and win the day in any future battle.

Sometimes a metacognition ends up as a disjointed ramble of thoughts and feels (and maybe is) a jumbled expurgation of contradicting thoughts. But that is fine. It is what it is…. Other times, it may flow together so cleanly and fluidly that it comes out as a pure and unified essay that reeks of the nuanced wisdom and strong wine of distilled thought, which is just as fine, yet infinitely more rewarding, more refreshing, and more fit to be shared—if that is the bent of your indefatigable genius.

Do this. Give a damn and figure yourself out.

Be that genius…

by Fitz | Jun 8, 2020 | Essays, The Crafted Word Blog, Workshops

“Don’t let school interfere with your education…”

~Mark Twain

Grading is that part of a teacher’s life that should bring some kind of solace to our work. No doubt, it is an arduous chore most of the time for the sheer amount of time it takes to do it well, do it fairly, and to do it in a way that actually helps the student. I am the first to admit, that I rarely feel satisfied after a long round of assessment because I often wonder if I am a reptilian calculator or a warm-blooded human on a mission to inspire, cajole and enlighten a willing and eager student. We teachers (myself included) have to juggle the competing demands of reality with an objective mission to further a subjective aim—that of coaxing the best out of a myriad of living, thinking, feeling students who bring a mosaic of life onto the platter (and splatter) of our curriculums. Amidst the competing demands of a common day, doing what is best for them seldom coincides with what is best for me .

It really feels like (after thirty years of teaching) that I should have mastered the tools of the grading toolbox, but I certainly feel now that I have much to learn and do and practice to head off to my retirement—still some years away—with some sense of satisfaction that I am a “master of my trade.” I am cursed by my burdens of reflection that I am missing out on the path to enlightenment, for I am constantly doing what others do simply because it is what is being done or has been done for generations before me. I wonder if I actually have the strength or wisdom in me to rally academia towards a wiser and more just solution.

How much of a grade should be based on homework? Most of us have no clue what “home” is to most of our students, yet we continually assign homework that is graded like daily take-home tests. It adds several more hours of pressure to what is already an over-burdened day. Homework should never be a test, which usually only rewards the gifted—whether that gift is one of intellect, the gift of a stable and nurturing home free from distraction or the gift of financial resources to tutor, guide and direct a student through his or her paces outside of school.Teachers should teach in class and not expect a student to learn what has not yet been taught.

Parents and administrators have become masters at manipulating expectations and as teachers we are only the limbs and heads of some monstrous and manipulated marionette. For the good of our students and our school systems, teachers are tasked to do the bidding of forces we barely even know or recognize. Common core is never really “common” for it suggests there is actually a common student on whom to model these expectations. In our private schools (free from the constraints of common core) we have the equally insidious monster that expects those extra dollars and extra attention to bring a student further up the ladder and poise him or her well and squarely on the next higher rung towards admittance to an even more prestigious school. In both cases, we are removing the wing from the bird and asking it to fly.

If anything should be common, it should be common-sense. Parents deserve to know what their children are studying, and why. Administrators deserve to know how well a teacher is teaching what they have been hired to teach. Teachers need to teach what they know best, and if they don’t know it, to learn it well or beg to be excused—but don’t fake it, and don’t let myopic, budget-constrained business sense overrule common sense and make a fisherman rule over a farm.

I consider myself to be fairly well-rounded and open-minded enough (arguably, I am sure) but it seems like every professional day takes me further away from core of my passion. I am being asked to teach grit and resilience; I am being asked to develop the moral character of my students; I am being asked to instill honesty, empathy, respect and courage; I am being asked to eliminate prejudice and bigotry; in short, it seems like I am being tasked with shaping the form of a perfect society out of the hard-scrabbled flesh and bones of imperfect youth. Noble, maybe, but I would rather show all this rather than demand it. I bow and bend to these winds of pedagogical changes like a dory anchored outside of the harbor, but I don’t really go anywhere. Should I grade a kid on grit? Is there a way to assess courage or define lack of prejudice? Have schools become the arbiter of social change, policies and correctness? Will it be codified and ruined to the point where it can, should and must be graded? If so, there is money to made somewhere by some professional presenter to tell us how to do it–and soon it will edge and creep into another form of another demand in the life of a teacher.

And I will have to sit through it…

by Fitz | Apr 22, 2020 | Essays, The Crafted Word Blog, Workshops

I have been teaching, writing, playing and performing for over thirty-five years, while during these last ten years I have been given the time and space and support (and funds) to create a classroom and pedagogy that through stops and starts and a deliberate evolution of ideas and practices has come to be known simply as “Fitz English.” I have always been somewhat of a traditionalist in my approach to what I teach, but I have always been driven to improve the classroom experience in a way that empowers students to become more confident, fluent, and engaged readers and writers; moreover, I have never “clung to my ways” or to any “ways” for that matter! When something worked, I tried to make it better. When something did not work, it went into my overflowing bin of teacher trash–and a mighty big bin it is. I can only thank my students and an enlightened and indulgent administration for placing a sacred trust in my hands–for the learning and practice of effective and powerful writing and reading skills is a sacred trust, and a duty that any wise teacher lives through in every class he or she teaches.

I have been teaching, writing, playing and performing for over thirty-five years, while during these last ten years I have been given the time and space and support (and funds) to create a classroom and pedagogy that through stops and starts and a deliberate evolution of ideas and practices has come to be known simply as “Fitz English.” I have always been somewhat of a traditionalist in my approach to what I teach, but I have always been driven to improve the classroom experience in a way that empowers students to become more confident, fluent, and engaged readers and writers; moreover, I have never “clung to my ways” or to any “ways” for that matter! When something worked, I tried to make it better. When something did not work, it went into my overflowing bin of teacher trash–and a mighty big bin it is. I can only thank my students and an enlightened and indulgent administration for placing a sacred trust in my hands–for the learning and practice of effective and powerful writing and reading skills is a sacred trust, and a duty that any wise teacher lives through in every class he or she teaches.

The seven guiding principles of The Crafted Word are the product of my own education in the hardscrabble reality of the classroom. The seven pillars: Read, Write, Create, Share, Collaborate, Assess, and Reflect capture the essence of what it takes to enable a more profound and enriching experience of a sustainable and dynamic literary life. I try to give my students whatever they need to flourish in their next academic year; however, I try even harder to build a foundation and approach to reading, writing and content creation that will serve and guide them throughout the odyssey of each of their respective lives.

For a new person entering my classroom, the most noticeable feature of my classroom is what is missing–desks! There are no desks. There is, however, a large round table around which students can stand or sit on stools (not chairs). It is at this table where we meet to discuss the coming class period, to share the work we have completed, and to prepare for the coming project–and there is always a project to undertake.

There is a large library of books arrayed along one wall surrounded by comfortable chairs. There are a few computers set on a standing bar; there is a widescreen TV on one wall. There is a stage set up with a green screen and mics and lights; there are two alcoves set up as recording studios–but there is no pencil sharpener; there are no reams of paper on a shelf; there are no blackboards or whiteboards, or posters hung on the walls–only guitars and banjos and framed artworks. There is–and there has not been–any paper shared between myself and my students for over ten years. Paper is simply not needed and, for me at least, is simply an inefficient hindrance to the work we do.

For many teachers, the classroom seems like an anathema. The lack of paper seems foolish and unwise. The distractions of technology mixed with students plopped upside down and sideways on the floor and across the arms of comfortable chairs is more than they can handle. Few teachers are jealous of my room, yet I guard it jealously–though I am very eager and willing to share it (and the secrets it holds)–freely and openly.

There is a great fear that real teaching and real learning cannot happen in a room where motion, action, and relaxation intermingle–where sitting takes a distant second to standing, where reading and writing on iPads, tablets–and even phones–is encouraged, where every essay is turned into a video or a podcast, where a blog post is recreated in a multi-media portfolio, and where everything is shared with each other, oftentimes created with each other, and always respected by each other. I

If I sound like I am crowing like a rooster at dawn, I am; and I will keep on crowing until one of my students says, “This is too easy,” “I’m not learning anything,” or “You really should get another job.” I will keep on crowing until a parent can sincerely say, “My child did not learn enough or write enough,” “Where is the rigor or basic skills my child needs?” or “What a waste of a year my child had in your class.”

If I have not crowed so loudly as to turn you away, keep scrolling and let me show you what I mean and how this approach can work in any classroom. I have the gift of a well-created classroom, but the essence of what I am trying to do could be accomplished in my backyard in a circle of pumpkins. The site right now is a work in progress, but please contact me you have any thoughts that can help me continue to build on this approach and, as they say, “Make it better.”

Have fun and “give a damn…”

by Fitz | Apr 16, 2020 | Essays, The Crafted Word Blog, Workshops

Doing something which is “different” does not come easily to most of us. The wrestling team I coach will look at me sideways if I ask them to practice cartwheels. I’ve even heard that some professional football teams bring in dance instructors to teach their behemoth linemen the art of ballet and foxtrot. My point is that practicing “any” athletic sport develops your skill in another seemingly unrelated sport. The same is true in writing. Through practicing the skills and techniques used in different genres of writing, we can enhance the overall quality and effectiveness of the writing we love to do (or are required to do because of schoolwork or employment.) By practicing different styles and genres of writing, we learn to avoid the rut of developing a formulaic, predictable, and downright dull writing style—plus, you might even discover a renewed love and energy for a “new” kind of writing when you practice writing in an unfamiliar genre.

Over the course of the next few weeks, try and write in each of the following genres and styles of writing. I will post more detailed descriptions and writing prompts that span the many different types of writing, but it is up to you to give them a full-hearted try. Good luck and have fun!

1. Your Daily Journal: Every good writer keeps a journal that remembers the daily events of his or her life, no matter how mundane or common. A daily journal is a recording of your life as live it, and as such, it is a treasure trove of memories that you can draw from later in life—memories and snapshots that you can expand upon in a more formal writing piece any time you wish.

2. The Ramble: The Ramble (often called ‘free-writing’) is close related to the daily journal, but it is more of a free-flowing series of thoughts, ideas and experiences. It is a journey with your mind and heart and soul down an emotional and intellectual highway. The ramble does not have to have a formal structure, but it does try to find and focus on a specific theme, and it does try and punctuate and paragraph to the best of your ability. By defining a certain post as a ramble, you are freed from all criticism of your writing style and technique because you are simply on an exploration of yourself, and as such, it is hard to go wrong! Rambles are great fun and an invigorating exercise in writing, but it is what it is. Kerouac aside, it is a misnomer to call a ramble anything but a ramble. I have had many chagrined students who tried to pass off their ramble as a thinly disguised essay.

3. The Personal Narrative: Personal Narratives are the stories of our lives. By habitually practicing the art of storytelling through personal narratives, we practice the basic craft of the Short Story and the Essay. By telling the stories of our lives, we follow the main rule of all writing: write about what you know! I could write all day about the joy of Bungee jumping, and I still couldn’t convince a toad that I knew what I was talking about. But if I wrote about the day I watched people bungee jumping off a bridge, then I could probably get that toad to publish the story for me. I could be the protagonist, and my best friend forcing me to try could be the antagonist; fear of jumping into the unknown could be the conflict; standing up to my friend could be the climax; falling out of a tree when I was young could be my supporting facts; facing and trying to overcome my fears could become the theme of my essay/story, and when a reader can relate to your theme, they are able to recreate your story in their own imaginations. It might force them to think about their own fears, and in doing so, your story effects a powerful transformations in their lives. Every day and every experience is a possible personal narrative. If that experience means anything to you, it will mean the same thing to someone else because we are all tied together by our “common humanity;” we share the same emotional connections, but how we experience those emotions is infinite and infinitely varied—and that is why our libraries and bookshelves are filled, and that is why we all keep returning to the power and creative magic of literature. Think of everything you write as true literature.

4. Memoirs: The way in which a person affects your life is a profound statement of your values and an enduring testament a specific person’s influence on your life. A memoir is a type of personal narrative that paints a vivid portrait of an interesting and worthy character. Through images and actions, thoughts, feelings and memories you, as a writer, recreate the power and magic of someone who has left an indelible mark on your life. Every good novelist and short story writer is a master of the memoir because writing memoirs is the key to developing dynamic, real and empathetic characters, without which a story falls flat on its face!

5. Short Stories: Every writer is essentially a storyteller, but the craft of short story writing requires a discipline and attention to detail that most writers are not willing to undertake. A good short story effectively creates a powerful experience for the reader out of the writer’s imagination and experience. Most beginning short story writers bite off more than they can chew; they attempt to scale a high peak without first learning how to tie their boots. I will write more in a future post, but for now keep it simple: don’t write stories with a bunch of different characters. Two or three characters is all a good short story needs! Make the plot easy to follow, and be sure that there is a clear protagonist and a clear antagonist and a clear conflict. Most importantly, create characters that you can relate to on a personal level. If you are ten years old, make your main character a ten year old, because that is what you know best, and you can recreate experiences for your reader that are compelling and real. And remember that your first draft is never ever your best draft!

6. Poetry: Poetry is the highest art. A great writer is not always a great poet, but a great poet is always a great writer. Poetry is the hardest genre to pin down and say, “This is poetry!” Poetry is the rough gem of life polished to perfection. To write poetry, you need to simply ask yourself: “Why is this a poem?” A poem is more than thoughts expressed in short lines; it is the meticulous crafting, choosing and placing of words, lines, spaces, breaths, and stanzas that defines what you call a poem. This is all up to you as the poet. I can’t tell you what is and what is not a poem, but I can tell you that good poets read the poems of other good poets, and they spend huge amounts of time on their own poetry. With practice comes skill; with skill comes perfection, and poetry will only happen in this order. The first skill of a poet is to ask, “Why am I writing this?” The second skill of a poet is to ask, “Did I tell my reader something, or did I lead them somewhere and show them something?” Don’t give the meaning of a poem away, but do leave clues for the reader to find that meaning.

7. Personal Reflections: I love personal reflections. There are few joys greater than the opportunity to just “think about something.” At the highest level, a personal reflection is an intimate and high-minded conversation with our own self—a conversation that is focused on a particular subject, topic or idea. The personal reflection differs from the ramble because it refuses to jump from thought to thought. Like a ramble, it retains the “I” in the voice; however, it stays fixed on a theme that is expressed in some kind of thesis or guiding statement. It is, by nature, less formal than a topical essay by retaining a spontaneous and unaffected narrative flow that feels to the reader like it is coming directly from your heart. It always has a distinct beginning, middle and end, but it never loses the sense of an open and inquiring mind on a search for truth—and every one appreciates someone who is willing to explore their own assumptions. I often tell my students that a reflection explores the question, while an essay answers the question. A personal reflection asks of each of us: Why am I writing this? What am I writing about? What do I think about my topic? If I come to a conclusion, how did I get there? A well-written personal reflection is as powerful as writing can get; it is the best of your mind offered to the reader as a gift that the reader can share in, think about, and agree or disagree in equal measure. A personal reflection is the best of your thoughts distilled into an experience of words!

8. Literary Reflections: Writing without reading is like an egg without a yolk; the nutrients are there, but the flavor is lacking. Usually, when we finish reading something, we put it away on the shelf and convince ourselves we are impressed, amazed, indifferent, or profoundly moved. The literary reflection is an offshoot of the personal reflection because it does not try and criticize a writing piece solely on its literary merits, but rather it “talks” about something you have read purely on an emotional and intellectual personal level. There is almost no reason to write a literary reflection about something which you didn’t like reading. (That is what a “Review” is for!) Write Literary Reflections about literature that you feel is important for other people to read because you want them—your readers—to experience the same magic that you experienced. It’s like being on a sightseeing whaling boat and someone shouts out “There’s a whale,” and everyone turns to see the whale for himself or herself! They all appreciate your attentiveness, and in turn, you are pleased to point out the magnificence of the moment to them.

9. Reviews: One of the cool things about being in a writing community with your peers is the chance to write about and read about a whole assortment of books, movies, places, games and any other activity people your age love to do. We live in a world of reviews. We avoid movies because they get panned in the Boston Globe. We refuse to eat in a certain restaurant because it only has a three star rating in Gourmet Magazine. What many “reviewers” fail to realize it that what they write directly impacts a person’s very livelihood. The main job of a review is to tell your reader whether or not what you are reviewing lives up to the hype. If somebody is arrogant enough to say they are the best in town, then by all means, hold them to that standard. But if Al at Al’s Diner says he sells cheap burgers, it is up to you to tell us just how cheap his burgers are—and you might want to add in that you get what you pay for. I love reading reviews, but I insist they be honest and fair. Use common sense when writing a review: don’t give away the plot and ending of books and movies; don’t write a review about something someone else can’t experience. (That is what a personal narrative is for!) Make sure to balance out your reviews. If your reviews are all negative, you will soon get the rep as a negative guy; if your reviews are always positive and glowing, people will think you live in la la land.

10. Expository Essays: Everyone likes to be right, and the expository essay is the perfect vehicle to define what is—and what is not—right and true! The word essay comes from the French word, “essai,” which means “to try.” A good essay tries to defend a certain point (called the “thesis”) using logic and supporting facts, not personal opinion. You can’t say in an expository essay that the 2008 Celtics are the best team in history because they make you feel good about yourself (great for a personal reflection) but you can say they are the best team in history because the Celtics are the first team to go from last in the league to champions in a single year!

by Fitz | Apr 12, 2020 | Essays, The Crafted Word Blog, Workshops

The Art of Collaboration

Danny, Jimmy & Me

I

Mrs. Roeber never seemed to let Jimmy go outside, which, to my thinking as an 11 year old, was why he was so smart. Most days after school, I’d rush two houses down the street and get Danny Gannon to come out and play. Then the two of us would go to Jimmy’s house next door. If Mrs Roeber answered, she would always be polite and say something like, “Jimmy needs to catch up on some science work. Perhaps he can play later.” If Jimmy answered, he’d usually be out of breath from running upstairs from his basement “office” and plead with us not to give up on him—or at the very least go out back and talk to him through the basement window.

So me and Danny would sneak out back and lay on our stomachs on the pokey grey gravel outside his basement window. Five feet below, Jimmy would be doing his work at his workbench (which, in all honesty, was a pretty cool place). I always wished I was smarter, so I could do his work for him and get him outside to play. I was better than Jimmy at a lot of things, but those things never got graded, and most of those things you couldn’t appreciate until “later in life.” But, to my Tom Sawyer way of thinking, I preferred being outside and average to being inside and smart. Danny was an outside kid, and smart, too, and that always troubled me, but not enough to let it call my inside/smart: outside/not smart philosophy into question. Danny’s voice was always the one that tried to tell me that the sledding jump was too high, or that branch would not support my weight, or those snakes would bite, or that we couldn’t run faster than a nest of bees we just destroyed.

Once we got Jimmy outside, he was like a mad scientist: ”We’ll, just have to see how high Fitz can go on his sled,“ or, ”I’ll distract the snake so Fitz can grab it from behind,“ or ”Bees have been clocked flying at 80 miles per hour.“ Looking back, we probably seemed like the gang that couldn’t shoot straight, and we did tend to go our different ways as we grew older, but we always still manage to reconnect somehow, and it doesn’t seem like we are a day older. It’s kind of hard to put into words because Danny and Jimmy might not be the best friends of my daily life, but they will always be the best friends I need.

Just thinking of the three of us together is like a window opening to a cool and welcome breeze. And the coolest thing is the window is always there. It might be that the only thing we actually had in common was living next door to each other, but still, we made it work; we made it real, and we made it last.

No choice. No problem. We did it together.

II

Life was pretty simple with Danny and Jimmy and me. There was no forethought in doing things together. It was more just some manifestation of a primordial DNA strand that we responded to with a visceral enthusiasm bordering on mania. We are born to be tribal in nature. We expect and need to be a part of a community, for we know in our bones and marrow that we really can’t go it alone. There is no Huck without Jim; there is no Odysseus without Athena, and there is no you without some hand that will pull you out of the muck you have made of your life. Thank God for the primitive man patiently stalking some larger prey to have the primitive women scrounging for tubers, berries, grains and millet, which no doubt provided the greater sustenance. We live and breathe a collaborative atmosphere of trust and unfathomable magnanimity.

Then why I did I always hate group projects, but, more telling: why did I change my mindset and my actions?

I hated group projects because they never seemed like group projects. What seemed in theory to be group work was really like some industrial factory spewing its incessant belching of traditions with an unequal and unsatisfying distribution of work and wealth, where the smart kids continued to be rewarded the lion’s share of honors, while the poor students (myself especially) continually paired themselves with a misfit tribe of friends who accepted the inequities of the classroom as a normal and an immutable reality of life.

Danny, Jimmy and I went to the same schools: Jimmy was—and still is—brilliant beyond my wildest dreams. Danny, too, seemed way smarter than me and probably smarter than most of the smart kid, though tempered with a shy and steady reserve (which by teacher default kept him from the brilliant crowd) that often forced him into our regressive and unrepentant tribe. As close as the three of us were in the ecosystem of our townie neighborhood, our schools erected barrier after barrier to keep us apart. While in school those walls did an admirable job of keeping us apart, and so we were only able to collaborate in our feral joys outside of school. Jimmy was smart, but not arrogant, and never willingly sought the tribe that formed around him, for when the academic birds of a feather were called to gather together, he was soon surrounded by the peacocks and strutting roosters of Concord, all brilliant in their own ways and inclinations, while my tribe and I wore our B’s and C’s and D’s like gang tattoos on our bruised and battered torsos.

Really, not much has changed between now and then, and while kids nowadays are more polite and empathetic, and at least begrudgingly inclusive, the iron curtains in our classrooms are still there–just more subtly erected. The academically accomplished kids are almost insanely driven to preserve the status quo—and if paired with the less accomplished, they will go to extreme lengths to do all of the work themselves. They do not want their brilliance to be diminished by including the less accomplished, less fortunate, and less able, and they will labor far into the night to correct the sloth and ineptitude of their partners. Ironically, it is an ignominy that they will suffer in silence, mostly because “collaboration” is part of the rubric—and in the end they all need to say it was a collaborative effort, and kids like me who simply sprayed the red paint on a smoke-spewing model of Mount Vesuvius remained mute in the complicit code of silence that dictated our lives.

So the rich preserved their wealth, while the poor squandered the chance to make a mark on their yardstick of time. The paradigm was set long ago: one law for the rich; one for the poor. It always seems strange and telling that the rich suburban and private schools constantly tout the quality of their students and teachers, when in reality that are just exposing the “quantity” of wealth and resources at their disposal. It used to piss me off, and I was satisfied in a smug way that at least I saw through the smoke and mirrors, until a point in time not long ago when I realized that, as Jesus said, “There will be poor always,” and I just needed to redefine what wealth really is and how it is spread around a classroom. I needed to unearth the inherent wealth in every kid I taught and see every one of my students as a treasure trove of possibility and make everything they did together engage that same passion of Danny, Jimmy and me hucking stones at bee’s nests. Every kid has to have a pile of stones to throw at the nest and the legs to run as fast as he or she can; otherwise, there is no skin in the game, no shared risks—and, ultimately, no shared triumphs.

III

Every classroom in every school on the planet is a blessed mix of possibilities—rich or poor, enriched or impoverished—with a mix of talents, drive, will—and more than a share of abnegating responsibility. As a kid, I hated group projects, and this hatred has fed my myopic biases for the past fifty years. They sucked as a student because I was never a full part of the group—and as a teacher, the group projects sucked because I would see the same inequities I despised perpetuated in my own lame assignments. I kept unleashing the same monster that swallowed me in my childhood. I was stuck in the stream of my own inbred traditions, though convinced I was nobly doing my duty as a teacher.

My epiphany came when I realized that I never really taught what the word collaboration means. None of us can grasp the wisps of what we don’t understand, but I had aways just assumed that we had a common understanding of the word—to do things together (whatever that really means) but while reading and teaching Moby Dick with my ninth grade classes, I found myself one day discussing the crew of the Pequod—and what a wild mix of nationalities it is: native american harpooners, dreamy adventure seeking deckhands, carpenters, sail menders, lookouts, blacksmiths, cooks and mates all bound up in a common adventure. Roles were defined, but in the fray of the chase every man took to the boats towards a common and fathomable goal. And what a success it was until the monomaniacal Ahab stepped to the deck and pointed the Pequod in his obsessive direction—to kill the White Whale. What was collaboration became duty and fate.

In discussing that twist of the plot, we started a conversation about what collaboration really is, and by the convolutions of discussion, we extended the metaphor of Moby Dick to help us define what is meant by collaboration. Collaboration is a shared adventure with shared rewards wherein every person is due his or her rightful share—the share agreed upon before setting foot on deck. No collaborative effort is inherently equal, for our skills and strengths on any given project are too disparate—nor will the rewards ever be the same for we will alway reap in proportion to what we sew and tend and what we sign on to do—but the journey and the chase can and should be exciting and rewarding for everyone, and no one person should ever be allowed to alter the common purpose of the voyage, and every person has to accept the mundane roles on quiet seas and rise from the forecastle when all hands are needed on deck, and every man has to drop everything and pull on the oars in precise rhythm when chasing the whale—and, most importantly, every person needs to be on that ship for the length of the voyage.

The Pequot’s crew was hoping to sail home to Nantucket with a belly full of oil that could be measured and assessed down to the last drop, and every part of that motley crew would know and expect, and receive a fair share of the reward.

So now I not only love group projects, but I believe that they are the heart and soul of my classroom. They are what binds us together as a community. They are opportunities to share strengths and work through weaknesses and differences. They help us recognize and respect the dynamic power of uncommon backgrounds pushing towards a common dream—not merely a goal. They help individuals find new and deeper sources of strengths that he or she never fathomed before.

But collaborative projects are not all roses and perfume. As a teacher you have to accept that it will take twice as long as you planned, and if you can’t be flexible, you are no better than Ahab—while at the same time your students need you as a captain who is stern and unforgiving and expects duty to be dutiful, who gathers the crew on deck when need be and frees them to their chores without being meddlesome, and when the blubber of the whale is being boiled down in the tryworks, your classroom will be a bloody mess. And just as in life, people will bitch and moan and convince themselves that their individual effort and persistence is what is keeping the boat afloat–and if that happens, call the crew on deck again–and again if needed. True collaboration is an honest day of hard and dirty work, not a bunch of friends trying to pass off sloth as substance.

And well all is said and done, and your students are tired, bloody, and bruised, give them their fair share of the split—and reward them, damn it, reward them.

by Fitz | Apr 11, 2020 | Essays, The Crafted Word Blog, Workshops

Teaching Traditional & Modern Skills for Reading, Writing, Creating & Sharing in a Digital World

Create a Better Classroom

for You & Your Students

Teaching Traditional & Modern Skills

for Reading, Writing, Creating & Sharing in a Digital World

Video Essays

Creating video essays out of traditionally constructed essays bring a whole new dynamic and range of possibilities for every student. A hard wrought and well-crafted essay is no longer a static piece of paper tucked away in a teacher’s desk or stashed in a crowded hallway locker. It is a multi-dimensional project that is shared with the world. Check out some of these that were created by my eighth and ninth grade classes.

It’s Over: A Final Reflection

~Paul, Eighth Grade

https://youtu.be/yrLMWlrjuSU

A Trip with Thoreau

~Charlie, 9th Grade

https://youtu.be/VJHxL2B2HGQ

A New Way of Creating Rubrics

No longer will the term “rubric” create dread in your students. The Crafted Word Rubrics are not checklists; they are guides to help students respond to almost any assignment in a clear and confident way.

Try them out!

https://youtu.be/ZzKyhfUed0k

https://youtu.be/yUrdAFKiNmI

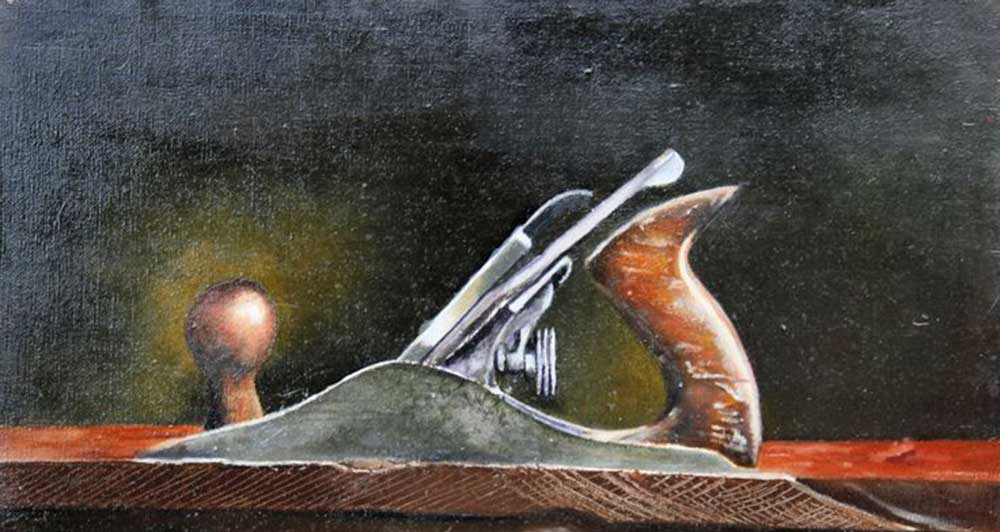

Few of us can do well if we don’t feel confident in what we are doing, but neither can that confidence be a misplaced confidence that is more succinctly called arrogance–a presumption of skill rather than an actual skill. Every time I create a teaching unit or plan a lesson–or even when I sit down to write something like this–I have to ask myself: “Do I really know what I am teaching, and am I teaching what I know in a way that all of my students are learning what I presume I am teaching?” I have to keep asking myself if I am the sage on the stage or the guide on the side; I have to keep asking if I am teaching essential skills and content or am I teaching what some reading workbook or English composition textbook says I should teach. Thankfully, at heart, I am still the shop teacher I have been for almost twenty years, but I am also the writer and teacher of writing I have been for more years than that.

Teaching shop is pretty cool because every kid comes into the shop with an untamed enthusiasm and eagerness to build something that is already in his or her head, and they are remarkably unfazed by their limited woodworking skills or by the scope of their dreams. I remember well an old student of mine who came into seventh-grade shop some years ago with detailed plans for building a one-man submersible submarine (as if you could build a non-submersible submarine:) and he begged me to give him a chance to try and build his design. Somehow he settled for something like a knapkin holder, but I heard the other day that he is now in Navy Seal training, so his ultimate dream never died; however, he learned that dreams can be realized and built out of a series of steps, an accumulation of skills forged out of the iron of real life and a dogged clinging to a vision of what he ultimately wanted to build.

Young writers (all writers) need that dream and vision, too. They need to love the possibilities that writing offers to build something as awesome and real as a six-board chest or a sparrow whittled out of a piece white pine. They need to go to the empty page with the same sense of possibility as the kid walking into the woodshop, and they need to want to learn the skills that will get them to a place they want to be as craftsmen and craftswomen of words and sentences and paragraphs and stories. Most importantly, they need a place and a way to learn and practice those skills: a workshop of their own to walk into and dream and learn and create.

The Woodshop as a Metaphor

THOUGHT: The woodshop is a metaphor for what should be possible in the classroom

Points:

- “Ah, the shop!” It smells good!

- They can move:

- They get to use cool tools

- They learn to “cut the board all the way through.”

- They need help–hence collaboration is natural and reciprocal.

- Their hands work as much as their heads.

- They own what they are building–and it has a purpose and a destiny.

- They get the teachers undivided attention–at least some of the time.

- The teacher leaves them alone–most of the time.

- Mistakes are fixed, not criticized.

- They “never” worry about their shop grade.

- They are surrounded by the future possibilities of shop class.

- They can see that building their toolbox is just a first step towards something like a boat, a chair, a bed, a table, a sculpture, etc: [We can do this in the classroom by having publishing parties, sharing digital portfolios, blogging—anything that allows students to see where their education is going.]

- There is a completion of a cycle: Though my students usually have smaller whittling projects going on the side, there is always one “big” project that takes them the entire term to complete, and it is always a source of pride.

- What you build stays with you for your life, if you wish.

How Is Your Classroom Experienced?

Thought…

Your classroom should reflect your students needs, not your comfort zone–and definitely not a pedagogy which is not your own.

Points…

- A class is a physical place but also a metaphysical place:

- We can alter both the physical and the psychical to create a better classroom.

- What does your classroom look like?

- Is it yours? Or are you part of the shared classroom model?

- Does it reflect that part of you that you want to reflect.

- What does your classroom feel like?

- Where do you sit, stand, or move when teaching? (There really is not a right way if it keeps the students engaged, interested, and ready).

- Is there any cool factor?

- Is your class any different than the classroom next door? Should it be?

- What is the temperature of the emotional warmth?

Experiment #1…

At your next faculty meeting have the faculty sit in rows of desks. Raise hands only if you know the answer.

- Only 30% can respond

- No talking allowed when leaving the room.

- The results of the problem are never published.

Experiment #2…

Have another faculty meeting where a common school problem or issue is presented and ask if small groups could possibly come up with some solutions. Have this group meet in a room with comfortable chairs or couches, and some refreshments. Let this group present their solutions to the rest of the faculty.

Respond To the Primal Needs of Your Students

Thought…

How do you respond to and prepare for the real and most primal and essential needs of your students?

Points:

- They need you to be genuine: if you can’t then you shouldn’t teach.

- Notice them. As much for the good as the bad. Class Dojo maybe?

- Say hello when they show up for class. Students need affirmation that they are welcome in your classroom.

- Give feedback–verbal, visual, & written. They need affirmation that their efforts on your behalf will never go unnoticed and unappreciated.

- Show students you care about more than how they are doing in your class. This is where the power of blogging is unparalleled. In the shop, the very nature of the mentoring makes kids feel connected because the shop teacher really is helping “them.”

- Say goodbye when your students leave: make some sort of tradition surrounding the end of class. Your students last impression is a huge one, so make your goodbye a good and affirming ritual.

- Have special days, reward days, random acts of “let’s do something different days.

What Does an Engaged Student Look Like?

Thought…

What does an engaged student look, act and feel like?

Points:

- What is Engagement and what does it took like?

- How do we create an engaging classroom?

- How do we nurture and sustain engaged students?

- How do we assess engagement?

- Create Rubrics, Folio’s, Videos, and blogging communities.

- You know it when you see it.

- An engaged student is willing and happy to figure it out.

- An engaged student feels like he or she has accomplished something worthwhile.

- An engaged student appreciates the value and or necessity of the content.

- An engaged student is alert, involved, and curious.

- An engaged student “can’t believe shop is over.”

- An engaged student will actually talk about what they did in class while driving home–and they might even bring it up on their own.

- An engaged feels like his or her time in your class is time well spent!

What Does a Disengaged Student Look Like?

Thought…

It seems like there are a few switches that engage students, but a lot more that turn them off and disengage and disaffect, so focus on what turns them on–and keeps them on!

Points…

-

- They can’t move.

- Everything is boring.

- The content and delivery is predictable.

- They can only use a pencil and paper.

- They work on their own—even when struggling with the basic concepts.

- Their heads are exhausted.

- Their bodies are exhausted.

- They’re hungry.

- They don’t know how to do what they are being asked to do.

- They only get help when they raise their hands.

- There is nothing palpable to show when class is done.

- They don’t know what they just learned?

- They don’t know how they did it?

- There is no endgame.

- The teacher hates them.

….And, yes, the list can go on as long as there is strength in the body.

Limits, Rules, Expectations & Values

Thought…

Kids spend a huge portion of their childhood in your classroom. What “family values” can and/or should carry over to your classroom?

POINTS…

- Set Rules, Limits, Expectations with the same passion and resolve as you would with your family.

- Let them in!

- Set rules, standards & expectations.

- Create traditions.

- Do fun things together.

- Laugh a lot and tell stories.

- Point out right and wrong. The moral compass!

- Forgive and Move on.

- Treat everyone equally. Get rid of tracking unless absolutely essential! It is a caste system by any other name.

- Treat each student uniquely: know your kids, accept them for who they are. This is quite different than being a “friend” to your students.

Create Possibility

I predict future happiness for Americans, if they can prevent the government

from wasting the labors of the people under the pretense of taking care of them.

~Thomas Jefferson

Thought…

We need to give our students projects and possibilities that they create, own, oversee, and present. We should not try to own what they create.

Points…

- There should always be a project going on.

- Projects should include collaborative and individual work.

- There should always be some sort of self-assessment.

- Students need to be able to claim genuine ownership, be free to pursue new directions and ideas, and exercise responsible and mature judgement when developing and creating that project.

- There needs to be an endgame of sorts–some way to showcase and curate that work for future generations to share.

The Power of Portfolios

Thought…

We need to create portfolios that capture and collate a history of every student’s journey through school.

Points…

- Collect. Collate. Curate: A new mantra for change!

- Our profession is only possible because of those who collected, collated and curated our bodies of literature, art, philosophy, history, and culture.

- Metacognition: It is important to remember, reflect and respond as a way of understanding who and how we are as learners (and teachers).

- Use journaling as a way to enable and practice metacognition.