by Fitz | Jun 23, 2020 | Essays, The Crafted Word Blog, Workshops

Write what you know.

~Mark Twain

I don’t always practice what I preach, especially when it comes to the simple, unaffected, and ordinary “journal entry.” Much of my reticence towards the casual journal entry is the public nature of posting our journal writing as blogs that are more or less “open” to the public. It is hard for me as a teacher of writing to post an entry that I know is trivial, mundane, and perhaps of no interest to my readers—but that is precisely what I need to do if I am to model the full spectrum of the writing process. Keeping a journal is more than a search for lofty thoughts amidst the detritus of the day; it is a practice that keeps our wits and writing skills honed for a coming feast by rambling through the meat of the day and drifting and sailing to whatever port is nearest to my pen. Writing is always an odyssey, and so I have to let my mind go and journey (journal) where it will.

Good words are built our of ordinary thoughts. At the very least, a journal, filled with the scraps and pieces of our daily lives, will outlive our own lives and serve as both beacon and reminder to future generations. Once, in my days as a junkman, I cleaned out an old barn in Maynard after the elderly widower—a man I only remember now as Bob—had died. Scrounging through the Bob’s boxes for anything of value, I came across a series of leather bound journals dating back to the 1930’s. I found a journal marked 1941, so I looked up the date of the Pearl Harbor attack, eager for insight on the profound effect that day must have had on the common man of his or her time. I turned through page after page of impeccable script and learned that Bob and his family went to church in the morning, during which they sang certain hymns (hymns that I can’t remember now—but he did.) Afterwards, they drove to Stow for dinner with his extended family. He wrote about the meal, the weather, the condition of the roads, and, in two brief lines at the close of his entry: “The Japs attacked Pearl Harbor today. I trust President Roosevelt will know what to do.” And that was it.

At first glance, I saw a xenophobic racist putting blind trust in infallible rulers. I couldn’t reconcile it with the kind and gentle old man, and best friend to my best friend’s father, who had recently passed away. I didn’t see it as a window into another time and another mindset. In the arrogance of my youthful pride, I couldn’t appreciate the elegiac beauty of his day—a whole day devoted to faith and the full circle of family. It wasn’t until years later when I sat on the bench by the World War Two Memorial in downtown Maynard and scrolled through the scores of boys and men from this one small mill town killed in battle that I realized the full extent of my myopia. I should have sat in his barn for days and read every word from his journals and then, maybe, I could have seen the evolution of a person through the fullness of time through the clarity of still waters.

Maybe Bob’s youthful ramblings, tempered by the death of so many of his townsmen, could have somehow transformed into the pearls of laconic wisdom that old age should bring—pearls that would fetch a heady price in the market of the modern mind. The greatest tragedy is that we’ll never know. I offered the journals to his son, but he was content to have me throw the whole lot into the back of my Chevy pickup and pay me fifty dollars for the load I scattered into the fires of the Concord dump. The irony of tossing those journals away not more than 150 yards from the site of Thoreau’s cabin on Walden Pond remained lost on me for many years, even as I trudged dutifully to the Concord library to scour through the massive tomes of Thoreau’s own journals. The old man had done exactly what Thoreau believed was required first of any man or woman when he admonished all would be writers:

“I, on my side, require of every writer, first or last, a simple and sincere account of his own life, and not merely what he has heard of other men’s lives ~Henry David Thoreau, Walden

A further irony is that my own journals from my years between eighteen and twenty five years old, which filled a good-sized cardboard box, were also inadvertently tossed into the same dump by a roommate intent on purging all the junk we were accumulating in our Williams Road farmhouse. The Concord dump is now a series of perfectly sculptured hills slowly regaining the shape and character of the woods that Thoreau tramped and stumbled through 150 years ago. It is a noble idea funded by the well-intentioned, but a nobler action would be to dig through the mold and dirt of time and truly find what the past has to offer us, buried almost irretrievably as it is.

Poetry is what is left unsaid. The stolid words of brevity simply point us in a direction only the brave will wander, but through the daily words of an old Italian farmer, I found a new kind of poetry. Pine Tree farm, butted against the rail line on the far side of Walden and owned by the Ammendolia’s, was one of the last of the Italian family farms that used to be scattered in every corner of Concord. Tony Ammendolia was the patriarch who somehow kept the dream alive, even as farm after farm succumbed to the teeming aorta of suburbia. It was there where I worked on school breaks and on summer weekends, picking corn at 4:00 AM before the heat of the day and hoeing seemingly infinite rows of tomatoes, beans, pumpkins, and eggplants in the long, hot afternoons where success and failure crisscrossed and intersected in a struggle to just get by. My Goddaughters were raised there, and their parents, my good friends Deb and Jack, still keep a few acres going to this day. Tony died two years ago after defying for many years the cancer he fought with the same stubbornness that he did the vicissitudes of nature in the cycle of droughts and floods and insects he faced at every turn during his days as a farmer.

Every night for over sixty years Tony would sit at his desk after dinner and write in his journal. Tony knew I was a writer and would kiddingly tease me that he was a writer too, but in a good-natured poke at my transient approach to life, he was also a farmer. I was at Jack and Debs recently for dinner and asked about Tony’s journals. Jack perked up as the proud inheritor of this family treasure and immediately found me one of the many small notebooks that Tony kept. I opened it and felt the tears well in my eyes, for it read like a type of poetry I had never read before. Tony never meandered from the scope of his own life, but his words spelled out a conviction that celebrated both the common fragility and majesty of life with sentences both sparse and foreboding: “Potato beetles got the eggplants on Bedford Street. We will not sell eggplant this year.” “Three days of rain. Lucky, as the irrigation pumps needs a new valve.” Each entry is a sublime excising out of the ordinary: the sky, the temperature, what was done, what had to be left undone, how much seed, what was selling and what was not selling—but never a mention of the money made or not made. There is never a mention of personal angst or frustration for over sixty continuous years. Those details were best left to imagination and speculation. Some, myself especially, have to call it poetry.

Our own journals need the same attention that Bob and Tony put into their daily records so that our journals can also chart the common unfolding of our lives. As writers and sojourners in life it is our call and duty to map the expanse of our existence. We don’t need to lay our souls bare for all to see and gossip about, but we should find a place to keep a daily journal. Whether it is written in leather bound journals, spiral notepads, or saved as private or public drafts in your blog doesn’t matter, but just a few short lines each day will serve to spark your memory in a later age—and memories wizened in the vat of a thoughtful life will always produce a finer wine. Journaling is a word that has been antiquated before its time. Though fewer and fewer of us take the time to sit with pen and paper, there is still a time and a place for the spirit of journaling to continue.

Make the time to map your own quest. A friend asked me yesterday why I didn’t have a GPS in my truck. He simply shook his head when I answered, “First, I have to remember where I’ve been.” Today’s technologies offer us possibilities unimagined to our literary forbears. Our daily journals can hold both pristine images of our lives via photos, video clips, and music, and most importantly, words. The web allows us to scour the world for like-minded souls that share our particular interests with whom we can share our passions on sites like Facebook, blogs, or personal web sites.

My only issue with much of what is out there on these sites is their self-exploitive and indulgent banality. Bob and Tony’s journals seemed permeated with an almost religious devotion as they chronicled the recitations of their days in rhythm with the pattern of their everyday lives, while on the other side, many Facebook sites I have visited have a tiresome and sycophantic obsession with the painstakingly mundane and profligate side of that persons supposed interests and lifestyle. It is hard—and sometimes impossible—to wrest any kind of context out of the content. Nothing, except a prurient curiosity, keeps me interested—and that is no road to enlightenment for either side of the equation. On some few sites there are links to blogs and other artistic websites where a deeper and more invested side of that person comes through. For them, their Facebook page is simply an adjunct to their life—a social gathering place to rest and draw water with friends and community. There is nothing wrong with that, but it should never be the destination of your journey, and if you can’t see life as a journey—an odyssey of existence—then you simply can’t see.

I guess the word I am looking for is devotion. None of our lives are more complicated than Bob or Tony’s lives. All they did that is different is make time to look closely at what was important to them in the daily unfolding of each of their lives.

Take the time.

Remember where you’ve been.

by Fitz | Jun 22, 2020 | Essays, The Crafted Word Blog, Workshops

Explore, Assess, Reflect & Rethink

How to move on to a better tomorrow…

For most of us teachers, our first crash course in remote learning is done, and the wise work now is to separate the wheat from the chaff and truly assess what works and what can be cast aside as detritus from a noble effort. I have always required my students to write a “metacognition” after each assignment as a way to explore, assess, reflect & rethink their unique experience of a common assignments and assessments. These dreary, one more thing they have to do drudgeries evolve over the course of the year from stuttering incantations of frustration into honest and compelling reflective exercises that reflect the “meta” of “cognition” in rich and nuanced narrative voices.

As educators, we would be wise to do the same while the bloom still clings to the vine and the muddy dew is still fresh on our hands. No doubt, it seems that remote learning is not going away. The likelihood of the coronavirus magically slipping into mere memory diminishes with each passing week, so yes, we need to prepare, but no, we do not need to make rushed and hurried decisions and leaping into professional development until we are sure what needs to be and can be developed over the course of the summer and before the looming reality of “The Fall Semester.” My cantankerous and curmudgeonly self already fears the slew of opportunities hell-bent on doing me good. I am an old and hardened soldier leery of being pushed into the mud before I dance to the old songs I know.

It would be handy and convenient to simply accept that “We’ll listen to the experts,” but who is to say with clarity who these experts are? As a teacher, I would answer, “We are! Each and every damned one of us!” We have all had our flashes of brilliance, and we have all had, more than likely, our share of fizzled duds, but we are, by and large willing to transform what we know into what we need to do. To administrators I say, “Give us the tools and let us build our own castles on the foundation of our unique school communities.” If we are unwilling or incapable, then by all means dictate and proscribe what you will in ladled dollops of wisdom and stubborn persistence. To students I say, “Be the kid who figures it out; not the lazy slouch who figures a way out. This is your new and inescapable garden in which to wither or bloom.” To parents and guardians I say, “Embrace the beast and do your best to tame the wild urges to let it run wild. You are no less a part of your child’s education than any teacher or school. You are the model of your child’s future, so be strong, wise and demanding.”

Oh, to be a fly on the wall to hear the chats of our students, the mumbles of our colleagues, the scrambling of administrators trying to put this whole ecosystem together, and the exasperations of our parents as education morphed from walking in to logging on; from engaging in the sensate repartee of the classroom and the bustling of a school community, and shifting on the fly to the hard screen of Zooms and uploads, halting connections and distracted, unkempt students still deep in the torpor of sleep. Even as summer begins, most of us are tired and weary. We live in a world that is cobbled together with loose stones and thin mortar. It is easy to lose faith and fear all that lies ahead. For the past three months, school was not what it was, and in many cases, not what it should be, yet, somehow much of it worked, and often to an astonishing degree. On successive days we have all been the hero and then the fool. In spite of any and all frustrations, our own experiences must now shape a new paradigm that can–and must–work.

Our lives and our experiences must become the parable that guides our future. We should start by imagining or reliving those babbling and disjointed conversations of what was good and what was bad, who was right and who was wrong, what worked and what didn’t work. We need to focus on our individual successes as teachers, our efforts as students, our thoughtfulness as administrators, our undeniable rights and roles as parents, and we must explore, assess, reflect and rethink–and separate the wheat from the chaff. That cannot begin until there is and acceptance that education is a three-legged stool; that there needs to be true and searching reflection on the parts of educators, students–and parents, for we all play an equal role in the dynamic that determines the success or failure of the second iteration of Remote Learning 2.0.

It is a new day and time for new ideas. The bell tolls for you…

And us.

by Fitz | Jun 22, 2020 | Essays, The Crafted Word Blog, Workshops

Words matter. Words carefully crafted and artfully expressed matter infinitely more. There is something compelling in a turn of phrase well-timed, arresting image juxtaposed on arresting images; broad ideas distilled into clear, lucid singular thought. For the writer, it is empowering to know that his or her words have the capacity to engage and effect change, to alter perceptions and persuade a living audience–not merely to share stale thoughts and shallow opinions, but to articulate what needs to be said in a wall of words that will stand the test of time and speak powerfully to the present generation and inspire succeeding generations.

Words… these damn words clabbered together–they are our gift to eternity. Learn how to use words; learn how to craft them together, and learn how to live the life of a writer. If you want to be a writer, live the life of a writer. It really is that simple: if you want to be a writer, live like a writer. Read. Write. Create. Share. Don’t push a loaded cart up a slaggy hill. Let the engine pulls the train. Learn the craft and the art will follow. You don’t have to be the drunk stumbling down a dark road howling inanities in the night, but even that is better than not howling at all. Howling is the birth before the epiphany, but after the primal howling in the dark, after the grimacing at fate, give the time and the space needed to till, plant and sow a more perfect garden with the seeds of your original cowlings. Nurture that garden as a farmer of words and bring your fruit to the market. It may well that your basket comes home more full than sold, but you are now the farmer of your mind and soul and heart and being, not the hungry pauper trying to fill a crumbling sack, scrounging for cheap seconds at before the shutters of commerce are drawn.

“A stitch in time saves nine,” or so the old adage goes, because a writer is a weaver of tapestries. Everything we write is a new mosaic of woven cloth–an original expression of who, what, when, where and why we are at any given point in our fleeting existence. We are not born weavers, but all of us have some rudimentary concept of a needle pulling thread. We understand the process. Every time we speak, we are stitching something together, weaving together words, struggling to hold together a wretched pattern of thoughts into a coherent conversation worth having; however, our opinions too soon fray and are soon too tattered to wear and are equally too soon forgotten.

But not so for the writer. The true writer goes back to that tattered, convoluted and forgettable conversation–an interplay of words sown, no doubt, with strong seed on thin topsoil where even the heartiest of intent withers on a dry vine. True writer do not give up on possibility; they go back and rebuild those same words and thoughts into a more perfect and palpable tapestry–a living and breathing garden of mind-swollen and succulent fruits worth bringing to market. What starts as a rambling in a journal evolves into something that resembles clarity and, ultimately, something worth sharing. It does not, however, just happen because we want it to happen. It happens because we make it happen. It happens because we learn to weave and stitch, and we learn to till and plant and cull the good from the bad.

The recipe for success is as old as time: learn, practice and persist. As a teacher of writing and as a writer, I am simply one of many pointing my finger at the moon. Your journey is uniquely your own. If you are not thirsty, then every well is the same. But if you are thirsty, go to the deepest, purest well and drink deeply until you are filled or have sucked it dry. To live the life of a writer is to live with an unquenchable thirst for that purity of thought etched upon a page of time. Your journey to the moon itself is distant and dangerous, and even the moon has only a reflected light, but everything you write serve as waypoints to map your journey–these linear dots arcing across the universe prove you have escaped the lure of gravity and the myopic confines of the muddy orb of earth.

That journey proves proves you are a writer–that you have not chosen the easy path with words, but the path of the explorer, the weaver and the farmer… and that is always worth it in the end.

by Fitz | Jun 18, 2020 | Essays, The Crafted Word Blog

What’s so important about this literary analysis paragraph thing? Maybe you won’t be spending your life analyzing literature. Maybe this is some academic exercise that is ultimately no big deal in the greater scheme of your life.

Or maybe it is…

You will always be measured, remembered and assessed for the clarity of your thoughts, for your ability to cut through the clutter and discern the truest essence of truth, and for the magnitude, breadth, and depth of your thoughts when conveying this truth. Your way with words is the yardstick that measures the weight of you who you are and ultimately defines how you are perceived and evaluated. Writing and speaking well is not a dream to be toyed with; it is an action that is perfected by sustained action embedded in the power of language—the only real and memorable way we communicate with each other.

I am simply a teacher, albeit, an annoying demagogue who is insisting on your grasping at something that is no doubt just beyond your reach, and frankly, just beyond my reach as well. I am sure it frustrates you as much as it frustrates me. You are so close to reaching it as much as I feel I am teaching it, so we have to keep playing this game of cat and mouse and trust that some moment of epiphany is just around the corner, that your work and mine is not in vain or an exercise in vanity.

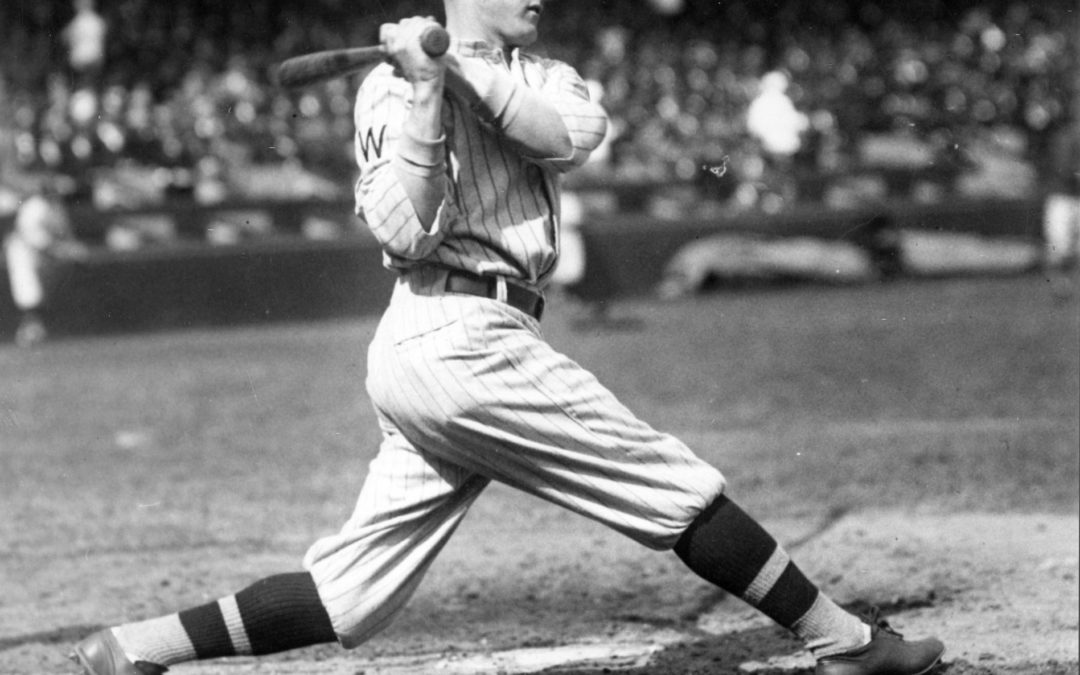

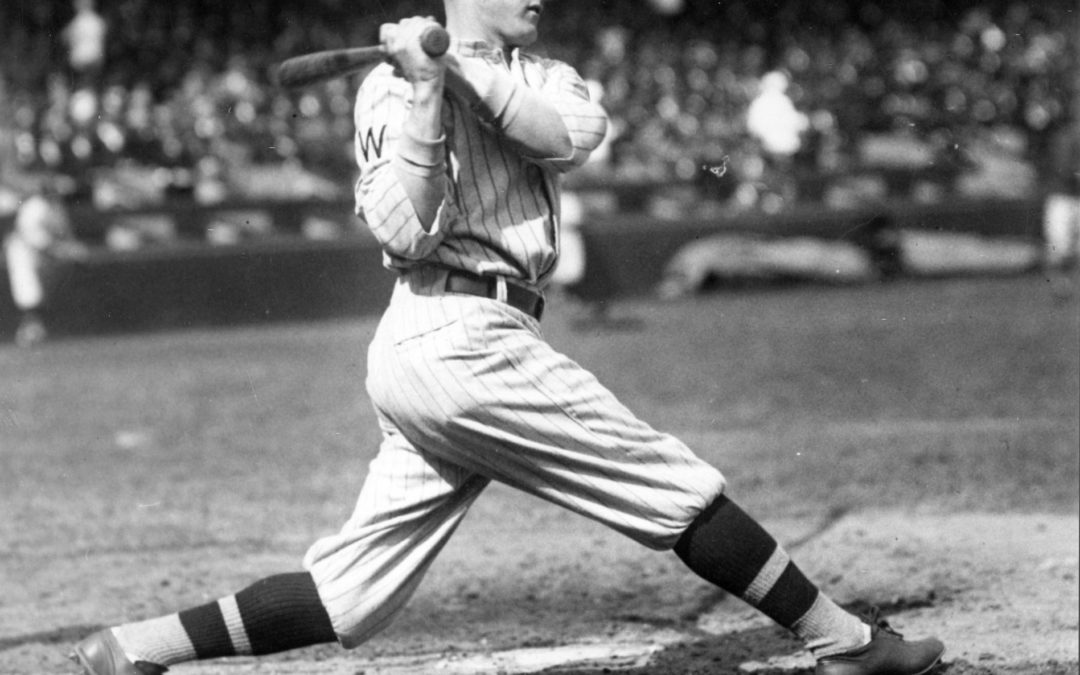

This literary analysis business is a lot like a baseball game: if you even manage a hit every three times at bat, you are considered a star; if you manage to hit a homer once—just once—every ten times at bat, you are proclaimed a hero, destined to be celebrated and remembered through succeeding ages, but no one is impressed by batters who are content to only swing in a batting cage, or by players who wait for walks or for easy lob balls dribbled remorsefully into the infield. Your game right now is on the line; the bases are loaded; there are two outs and you are down by three, and now it is all up to you.

So swing, dammit, swing. The ball is straight down the pike. It is your moment and there is no tomorrow.

by Fitz | Jun 16, 2020 | Essays, The Crafted Word Blog, Workshops

The Rules of Punctuation

If you don’t use it, you lose it…

~Fitz

What do you really need to learn? What teaching and what practice will help you learn what you “really need to learn” in a way that will somehow stay with you and be useful and necessary to your life.

Most all of you are pretty lucky I did not “grade” your most recent essay harshly for missing and misused punctuation, though I probably should have graded those few students who were in my class more harshly. It’s only fair. I practically beat them over the head last year with comma rules, hyphens, long dashes and semi-colons, brackets and the weird three-dot thingy. If they have forgotten, I blame myself. What kind of English teacher can’t teach what is basic and critical to good writing?

Me, I guess…

I think when the average teenager hears the word “rules,” he or she immediately starts building a wall to keep that rule out of mind and out of sight. It’s too bad because rules are what keep us going, and if we don’t keep going, the fun ends. Imagine Fortnite if someone hacked the system and no one could be blotted off the screen? Imagine the millions of whining men and boys across the world having hissy fits and swearing into headphone mics when their perfectly placed snipe had no effect on the clueless soldier hopping across the screen?

Imagine soccer without goals. Imagine bread without flour. Imagine the earth without a sky. Imagine words could be any jumble of letters. Songs could be any arrangement of notes–parents could choose their kids and kids choose their parents…

Get where I am going?

And what does this have to do with punctuation?

Punctuation simply connects “thoughts” (clauses) and “fragments of thoughts” (phrases) together in a way that mimics and reproduces the effect of an ordinary conversation–or a profound rendering of poetry, or a stupid and insipid movie you wasted ten dollars going to see on an otherwise perfectly fine Friday night. As far as the written word goes, the rules of punctuation follow the laws of physics. Without them, nothing holds together.

Where does this leave you, coming with trepidation to the assignment page?

It leaves you in the crosshairs of a cold and calculating teacher measuring the distance between himself and his unsuspecting students–measuring their capacity for genius; discerning what exactly will help them learn, remember, practice and use “The Rules of Punctuation.”

You will find that The Rules of Punctuation are a beast you cannot slay; you cannot avoid, and you cannot ignore.

Your only option is to Embrace the Beast, wrestle it down and hold it down until it is tame, and when it is tamed, morphed into a friend and ally, it will follow you around the rest of your life and will always be faithful to you, protect you and strengthen you.

And maybe then you can pen a letter of thanks to me, long since retired and living off the memories of students who actually gave a damn and made something with their lives.

by Fitz | Jun 14, 2020 | Essays, The Crafted Word Blog, Workshops

So much depends

on the red wheelbarrow

glazed with rain water

beside the white chickens.

-William Carlos Williams

It was funto be swimming and clambering around with my kids yesterday in a remote stream in the Berkshires and thinking: “This would be a cool experience to blog about!” People ask me sometimes if encouraging people to get on the computer is a “good thing.” As with anything in life, it is only a bad thing when it is used un-wisely or at the expense of living your life to the fullest. As I write this on my back porch, Charlie is swinging on a rope swing, EJ is collecting ants for his ant farm while Tommy investigates and shouts with joy at every caterpillar he can find. I am eager to pack up the bus and head to the Cape and get my old sailboat in the water, so I can spend longs days (and some nights) cruising around Pleasant Bay and Vineyard Sound.

After years of teaching writing, I can say with confidence that personal narrative writing is the number one BEST way to improve the overall quality of your writing. You have to have experience before you can recreate that experience—a lesson often lost in classrooms.

Personal Narratives are the stories of our lives. By habitually practicing the art of storytelling through personal narratives we practice the basic craft of the Short Story and the Essay. By telling the stories of our lives we follow the main rule of all writing—write about what you know! I could write all day about the joy of bungee jumping, and I still couldn’t convince a toad that I knew what I was talking about. But, if I wrote about the day I watched people bungee jumping off a bridge, then I could probably get that toad to publish the story for me. I could be the protagonist, and my best friend forcing me to try could be the antagonist; fear of jumping into the unknown could be the conflict; standing up to my friend could be the climax; falling out of a tree when I was young could be my supporting facts; facing and trying to overcome my fears could become the theme of my essay/story. When a reader relates to your theme, they are able to recreate your story in their own imaginations. It might force them to think about their own fears, and in doing so, your story creates a powerful transformation in their lives.

Every day and every experience is a possible personal narrative. If that experience means anything to you, it will mean the same thing to someone else because we are all tied together by our “common humanity;” we share the same emotional connections, but how we experience those emotions is infinite and infinitely varied—and that is why our libraries and bookshelves are filled, and that is why we all keep returning to the power and creative magic of literature. Think of everything you write as true literature.

As a way to begin, don’t get bogged down by form and structure, but do ask yourself why you are writing about that experience, and do ask yourself “How am I telling my story?”.

Here are ten ideas I keep in my head when writing a personal narrative. These ideas also work for any type of short story fictional or real:

Put a man in a tree. Throw stones at him. Get him down: That is to say, whenever we write a personal narrative or a short story we need to create the scene, show the conflict, and then show how that conflict works itself out. A narrative without any form of conflict is like an egg without a yolk: it is simply (and sadly) not a good story.

Make sure your reader has an idea of where you are taking him or her “early” in the story. Nobody likes to get in a car blind-folded with a stranger and have no idea where he or she is taking you. You will jump out of the car at the first chance you get! You don’t need or want to be specific right away about where you are going with your story, but you certainly want your reader to feel like it is going to be an interesting ride. A simple strategy is to make sure that somewhere (preferably at the end) of your first paragraph there is some kid of guiding statement or foreshadowing technique that assures your reader that your story is going to be worth ride.

Use specific images and actions to tell your story: Always remember that your reader is not “in your mind.” They can’t see what is in your head until you “show” them. Use nouns and verbs to create those images and actions. Your readers can put together nouns and verbs without much difficulty. Use adjectives and adverbs only as a way to help your reader—not distract them. The “red wheelbarrow, glazed with rain water beside the white chickens” is a great way to “paint a scene.” If William Carlos Williams wrote the same line as, “the chickens are next to the wet wheelbarrow,” then his poem would probably have died after a short and unnoticed life.

Well chosen dialogue makes everything you write come alive: Words spoken by people who were with you act like supporting facts in an essay. They are proof that what you say is true, and serve to engage another part of your reader’s senses. Remember to always lead into a quote by setting the scene; don’t just drop dialogue int a writing piece with no context to “hear” that dialogue spoken.

Punctuate as well as you can: For the most part, punctuation is all about the comma—everything else flows from understanding of when and where the comma works best. In future posts, I will deal with commas and other punctuation in more detail. For right now, just be aware that punctuation (a relatively recent part of the creative process) simply helps your reader experience what you want them to experience in the way that “you experienced that event.

Use paragraphs to lead your reader through your story: Contrary to what we are often taught, there is no minimum or maximum “length” for a paragraph. In a short piece, short paragraphs work fine. Long paragraphs work well in longer pieces. As a suggestion (not a rule) have the first part of your paragraph indicate the direction or idea you are going to write about. (I call those sentences “guiding themes.”) If when writing or editing you find yourself “off of the idea,” then simply start a new paragraph.

Try to end your story by leaving your readers thinking, wondering, wowing, squirming or relieved: Just don’t leave them hanging, and don’t end so abruptly that they feel cheated out of well-told story. If your story is well told, the ride is always worth it.

Proofread before you publish: Spell-check, fix, change, delete, move, and do whatever you need to do to be happy with what you’ve finished (or thought you finished:). It is only easy if you try.

by Fitz | Jun 12, 2020 | Essays, The Crafted Word Blog, Workshops

Know Thyself… Explore, Assess, Reflect & Rethink

If we don’t learn from what we do, we learn little of real value. If we don’t make the time to explore, reflect and rethink our ways of doing things, we will never grow, evolve and reach our greatest potential or tap into the possibilities in our lives. Writing metacognition’s is our way to explore our experiences as students and teachers, and then to honestly assess our strengths and weaknesses, to willfully and wisely reflect on what we did—and did not—do, and to rethink how to move forward in a positive and more enlightened way towards a better and more applicable and capable future.

There are many sides to every experience, so when I ask you to “explore” an experience and write a metacognition, I am not looking for a simple summary of what you did. I expect you to write like you are walking the rocky and jumbled coastline of what you just went through. Recount and relive your experience in a stream of deliberate, dreamlike consciousness. This recounting and reliving can be as scrambled and unkempt as your emotions and memories; there is no “Fitz Rubric” to follow; there are no specific“details” to the assignment—there is only you and your own heart that you can follow with your own iconoclastic bent, will and resolve. You do not have to worry about being understood by your reader. You are only trying to understand and know yourself.

When you assess, there is no way around the need for a bit of cold and reptilian critique. Looking with clear eyes upon yourself is a hell of a hard task, but it is part and parcel of a thinking person’s package. Sure enough, the assignment might be so flawed as to be undoable, but that is, I hope, fairly rare. More likely the great flaw (or the great promise) starts with you, your attitude, and your way of tackling the work. And it ends with you. Pull out a scale and a measuring tape and tally what you produced; weigh it against the scale of time you stole from your life to complete the work, and ask yourself: do you feel like saying, “Check it out,” or do you feel like sighing, “Chuck it out.” To assess is to figure that out.

Once “that” is figured out, your head should kick into full reflection mode. A reflection scours the deeper trenches for whatever insights can be culled from the briny mud of experience. Pull these thoughts and splay them on the deck as they come, for they are all gifts from the sea of the mind, and their true value can be discerned later and kept or cast as wanted or needed. There is no such thing as unwanted catch in a reflection.

If you are unwilling to rethink your actions you are, to use an old adage, condemned to repeat that action. By rethinking approaches you can retool the machine of your being, and in that sense you are continually reborn as a better you. You make sense of yourself and are now clad in a stronger armor with a shield,pike and sword better suited to turn the tide and win the day in any future battle.

Sometimes a metacognition ends up as a disjointed ramble of thoughts and feels (and maybe is) a jumbled expurgation of contradicting thoughts. But that is fine. It is what it is…. Other times, it may flow together so cleanly and fluidly that it comes out as a pure and unified essay that reeks of the nuanced wisdom and strong wine of distilled thought, which is just as fine, yet infinitely more rewarding, more refreshing, and more fit to be shared—if that is the bent of your indefatigable genius.

Do this. Give a damn and figure yourself out.

Be that genius…

by Fitz | Jun 9, 2020 | Essays, The Crafted Word Blog

Trying to pull a final day

Back into the night, execute

Some stay of time,

Some way to wrap

The fabric of Summer

Around the balky,

frame of Fall, sloughing

My skin, unable to stop

This reptilian ecdysis—

This hideous morphing

Into respectability.

My students, tame

As lab mice, won’t understand

My unblinking eyes,

The hissing of my speech,

The expansive hinge of my jaw—

Or my insatiable appetite—

Until I swallow them whole

Into my elongating belly, feasting

On their impeccable,

Transient joy.

by Fitz | Jun 8, 2020 | Essays, The Crafted Word Blog, Workshops

“Don’t let school interfere with your education…”

~Mark Twain

Grading is that part of a teacher’s life that should bring some kind of solace to our work. No doubt, it is an arduous chore most of the time for the sheer amount of time it takes to do it well, do it fairly, and to do it in a way that actually helps the student. I am the first to admit, that I rarely feel satisfied after a long round of assessment because I often wonder if I am a reptilian calculator or a warm-blooded human on a mission to inspire, cajole and enlighten a willing and eager student. We teachers (myself included) have to juggle the competing demands of reality with an objective mission to further a subjective aim—that of coaxing the best out of a myriad of living, thinking, feeling students who bring a mosaic of life onto the platter (and splatter) of our curriculums. Amidst the competing demands of a common day, doing what is best for them seldom coincides with what is best for me .

It really feels like (after thirty years of teaching) that I should have mastered the tools of the grading toolbox, but I certainly feel now that I have much to learn and do and practice to head off to my retirement—still some years away—with some sense of satisfaction that I am a “master of my trade.” I am cursed by my burdens of reflection that I am missing out on the path to enlightenment, for I am constantly doing what others do simply because it is what is being done or has been done for generations before me. I wonder if I actually have the strength or wisdom in me to rally academia towards a wiser and more just solution.

How much of a grade should be based on homework? Most of us have no clue what “home” is to most of our students, yet we continually assign homework that is graded like daily take-home tests. It adds several more hours of pressure to what is already an over-burdened day. Homework should never be a test, which usually only rewards the gifted—whether that gift is one of intellect, the gift of a stable and nurturing home free from distraction or the gift of financial resources to tutor, guide and direct a student through his or her paces outside of school.Teachers should teach in class and not expect a student to learn what has not yet been taught.

Parents and administrators have become masters at manipulating expectations and as teachers we are only the limbs and heads of some monstrous and manipulated marionette. For the good of our students and our school systems, teachers are tasked to do the bidding of forces we barely even know or recognize. Common core is never really “common” for it suggests there is actually a common student on whom to model these expectations. In our private schools (free from the constraints of common core) we have the equally insidious monster that expects those extra dollars and extra attention to bring a student further up the ladder and poise him or her well and squarely on the next higher rung towards admittance to an even more prestigious school. In both cases, we are removing the wing from the bird and asking it to fly.

If anything should be common, it should be common-sense. Parents deserve to know what their children are studying, and why. Administrators deserve to know how well a teacher is teaching what they have been hired to teach. Teachers need to teach what they know best, and if they don’t know it, to learn it well or beg to be excused—but don’t fake it, and don’t let myopic, budget-constrained business sense overrule common sense and make a fisherman rule over a farm.

I consider myself to be fairly well-rounded and open-minded enough (arguably, I am sure) but it seems like every professional day takes me further away from core of my passion. I am being asked to teach grit and resilience; I am being asked to develop the moral character of my students; I am being asked to instill honesty, empathy, respect and courage; I am being asked to eliminate prejudice and bigotry; in short, it seems like I am being tasked with shaping the form of a perfect society out of the hard-scrabbled flesh and bones of imperfect youth. Noble, maybe, but I would rather show all this rather than demand it. I bow and bend to these winds of pedagogical changes like a dory anchored outside of the harbor, but I don’t really go anywhere. Should I grade a kid on grit? Is there a way to assess courage or define lack of prejudice? Have schools become the arbiter of social change, policies and correctness? Will it be codified and ruined to the point where it can, should and must be graded? If so, there is money to made somewhere by some professional presenter to tell us how to do it–and soon it will edge and creep into another form of another demand in the life of a teacher.

And I will have to sit through it…

by Fitz | Jun 6, 2020 | Essays, The Crafted Word Blog

When I was a kid it was the dump.

Every Saturday morning my father and I would pile a week’s worth of trash into the back of our Plymouth Fury station wagon and head the to the Concord town dump. Back then the dump was a place of perpetually burning fires and massive heaps of discarded metal: bed-frames, lawn mowers, refrigerators and two centuries worth of bicycles. They would only haul the pile away when it reached mammoth proportions, when they’d lift the tangled webs of metal with a crane that looked to have crawled out of Mike Mulligan and the Steam Shovel. The crane had a massive magnet that somehow shut itself off and dropped the whole load into the truck with a deafening and fatalistic screech, though I could never figure out how that magnet shut off—much to the chagrin of my crew cut engineer father—something to do with a solenoid, I recall. I’d sit on the bumper and guide him as he backed up to the hottest fire. I’d then start casting everything in to the pit—I mean everything, whether it could burn or not.

My father would leave me to my primal sport and go talk to the other fathers (and very rarely, mothers) who were always gathered around talking: politics, the war, cars, sports, or just handing out schedules and town meeting agendas. As they talked about everything under the sun, I’d find some classmate (there was always a neighbor or classmate at the dump) and we’d heave hair spray, spray paint and empty almost turpentine cans into the fire just to watch them explode. Occasionally, after a really good explosion, someone would scream at us miscreants, but we’d just nonchalantly holler back, “Sorry, didn’t know it was in there,” and the adults would go back to their talking, and we’d go back to our heaving and blowing up of things. I sometimes wonder how anything gets resolved in Concord now that they no longer have a dump. I wonder where everybody goes where they can talk on an equal footing with their neighbor. We all need a place to meet and speak and converse in brave and honest dialogues, no matter what the venture, time or place—and so it is with our writing community in class: We’ve got to get out of our metaphorical cars and say, “How you do?” to our neighbors, even if we don’t know them from a hole in the wall.

So, I like to think of our class writing communities as the Concord Town Dump because it is good to have a place where everybody can gather and get the news from a common place. Words matter, and in the end it is through our words and actions that we will be remembered. We are all an equal cog in a wheel of writers, and without your blog there would be one less of “each other’s” blogs, and so our community of writers would be diminished by an infinite degree—the degree of your potential.

You will be measured and remembered by the words you leave behind. Words are remembered because they are memorable, not simply by virtue of being spoken or written down. A good writer strives to craft writing that is memorable for the reader, and a good writer will do so in the same way that a cook tries to make a meal that his or her guests will remember fondly—a meal that will make them want to come back again and again. We will go to that restaurant as often as we can, and we will read every book that writer publishes—and we’ll go to the best blogs in our community time and time again to see what the writer—hopefully you—has produced today.

There is another small scale (and often frustrating) irony that comes into play: the best writers are rarely the most widely read or popular writers. Henry David Thoreau’s books were scarcely read by his contemporaries in his day. He spent four or five hours every day writing in his journals and crafting his now acknowledged masterpieces of literature, with only a handful of people ever laying eyes on his lifetime of labor.

But Thoreau continued to write because he believed in the value of what he was writing—and you need to believe in what you are writing, not because of what he or she or me says about your writing, but because you believe in what you write; because you believe that writing is important and necessary and needed; and because you’ve felt (or will soon feel) the power, majesty and mystery of good writing, and learning to write well is a mountain you are willing to climb. From that mountaintop you will let the world see what you see and feel what you feel, and you will be a part of the great cycle of searching for meaning that keeps us human. You are much more than a kid wanting to be a better writer; you are the beginning of your greatest potential.

Keep writing. It always pays off.

Recent Comments